In poll season, a video captures J&K job distress: ‘Seen that PhD scholar selling fruits?’

While issues of identity come up in Kashmir, and “too much focus on Valley” in Jammu, a common refrain across the Union Territory is the need for the government to create jobs.

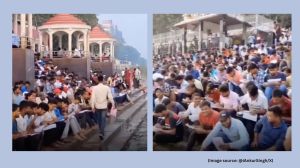

From Jammu University to colleges and coaching institutes in Srinagar, there is a palpable angst over the lack of job opportunities. (File)

From Jammu University to colleges and coaching institutes in Srinagar, there is a palpable angst over the lack of job opportunities. (File)Travel across Srinagar, talk to students or young job seekers, ask about their aspirations, and every second person recounts the same story to underline the situation. The story of a young PhD scholar selling dry fruits by the roadside. Most of them have seen the video on WhatsApp or on social media platforms.

Then, the conversation invariably leads to reservations – including in Jammu, which on most matters differs from its counterpart.

From Jammu University to colleges and coaching institutes in Srinagar, there is a palpable angst over the lack of job opportunities. In Srinagar, this is lined with rage over the Article 370 abrogation. In Jammu, few mourn the scrapped special status; rather there is apprehension that the “neglect” of the region because of “the intense focus” on Kashmir might continue if Article 370 is brought back.

The video that keeps popping up in conversations across Srinagar is of Dr Manzoor Hasan, who claims to be a PhD scholar forced to sell dry fruits on the roadside in Shopian in South Kashmir. In some posts, there is a small write-up accompanying the video.

In a written reply in the Rajya Sabha last year on the issue of unemployment in J&K, the government stated that the Periodic Labour Force Survey put the unemployment rate in the age group 15-29 years for the period July 2020-June 2021 in the erstwhile state at 18.3%. The corresponding figure for the rest of the country was 12.9%, in a period that covered the Covid pandemic and its stress on the economy.

The manifestoes of all major parties this time are promising more jobs. The Congress has said it will fill one lakh vacant government posts by issuing a job calendar within 30 days, while the BJP says it will create five lakh employment opportunities through a Pandit Prem Nath Dogra Rozgar Yojana.

Even regional political outfits like the National Conference and Peoples Democratic Party which talk of issues such as Article 370 restoration are making job promises. The NC says it will ensure one lakh jobs to youths and the passage of a J&K Youth Employment Generation Act within three months of coming to power.

Quota worry

Most of the youths link the “plight” of the PhD student in the video to what they too are facing, and to “the increase in reservations” impacting “open merit” students.

The “increase in reservations” is a reference to the Modi government move expanding the ST quota to bring in more tribal groups – a move that is also facing opposition from the groups that already enjoyed quota benefits in the Union Territory. The Centre last year announced a separate 10% reservation for Paharis under the ST category, and an increase in the quota for OBCs to 8%.

Junaid, a student at the Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir (SKUAST), says: “There is 8% reservation for SCs, 10% for Paharis, OBCs now have 8%… Then there is some reservation for economically weaker sections, those living in border areas, residents of backward areas… Overall I think the reservations have gone up to 70%, leaving the open merit students with just 30%.”

Kashmir ‘focus’

In Jammu, what happens post the new quotas is one of the worries regarding the changes ushered in after the abrogation of Article 370. The bigger one is “obsession” with Kashmir, which many in the Hindu-dominated province believe continues unchecked. “Everyone talks only about Kashmir, Article 370 and 35 A, the political machinations… There is little focus on Jammu,” a Kashmiri Muslim, settled in Jammu’s Bhaderwah and a student at Jammu University’s Law Department, says.

Another student adds that Kashmir remains the net gainer, even after the abrogation. “Article 370 was abrogated and Kashmiris got all the benefits. Jammu walon ko kuchch nahin mila (Jammu residents didn’t get anything)… The talk is all about the completion of already sanctioned projects (here).”

Even on the jobs front, says the student, Kashmir remains better off. “There is tourism in Kashmir. Kashmiri ghar baithe paise kama lete hain (Kashmiris can earn money sitting at home). There is no such tourist attraction in Jammu except the (Vaishno Devi) Mandir. Even the other mandirs and gurdwaras in Jammu are not developed from a tourism or pilgrimage point of view.”

Still, on the balance, things have moved in Jammu on the development front after the scrapping of special status and imposition of Governor’s rule, say students in the erstwhile winter capital of J&K, and they don’t want that changed.

In Kashmir, the abrogation of Article 370 remains the pinnacle of what is seen as the Centre’s “high-handedness” in the Valley – across years and across governments. “What we need is freedom of speech, freedom to move around,” says a student.

But, he adds, “what we need is also jobs”, and asks whether the ongoing elections for a government are any answer. “The elections are welcome, but will the new government have any power to create jobs? I doubt it.”

Coaching centres

The dilemma between the larger issues of identity and more mundane concerns such as jobs also plays out at the coaching institutes across Srinagar, which are packed. A student coordinator at one of the institutes, who has a Masters in Civil Engineering, returns to the theme of that PhD scholar’s video. “A lot of qualified youngsters, including PhD scholars and postgraduates, are taking up ordinary jobs which have nothing to do with their qualification… I have interviewed people with postgraduate degrees for the job of floor incharges and helpers at this institute,” says the coordinator who didn’t want to be identified.

Along with jobs, the issue that keeps coming up regarding youths in the Valley is rampant drug use. The student coordinator says this too is linked to the unemployment situation. “Why are youngsters in Kashmir moving towards drugs? Because they don’t have a stable income. Many are depressed. Paper leaks are another concern. I did my Masters in Civil Engineering from an institute in Rajasthan. All my batchmates got government jobs… I am here, as a student coordinator,” she says.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05