Opinion The Zubeen Garg we must not forget

Behind his tragic death and rising demands for justice lies the story of a self-made icon who never bowed to the mainstream, who stood at the intersection of culture, protest, and middle-class aspirations

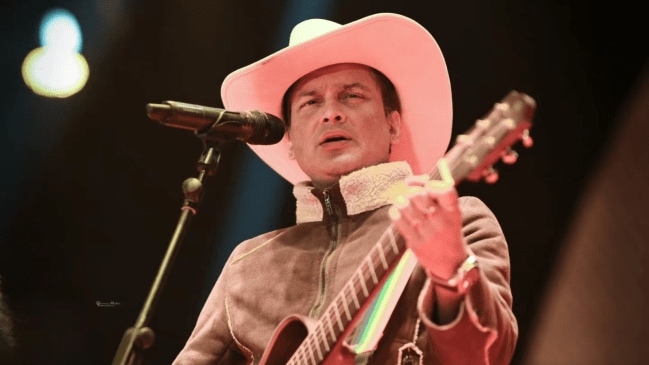

Listening to Zubeen sing, one senses an undefined pathos in his songs.

Listening to Zubeen sing, one senses an undefined pathos in his songs. Written by Bhaskarjit Neog

At a time when the slogan of Justice for Zubeen is getting louder in Assam with every passing day after Zubeen Garg‘s tragic death in Singapore, it is important to recognise who this extraordinary musical talent was — beyond the image that gets caught through a handful of his songs. As death makes many things clearer even for those closest to the deceased, perhaps for the people of Assam also it is a moment to reflect on what he was for them beyond his musical appeal.

Zubeen was a musician of extraordinary versatility — who sang nearly 38,000 songs across 40 different languages, wrote and composed hundreds himself, played dozens of instruments, and directed and acted in movies and videos, creating almost a cult-like phenomenon for nearly three decades in Assam. A fiercely independent mind, he made it a habit, almost, to make people uneasy — sometimes by uttering words that crossed the accepted bar of civility, sometimes by questioning people for addressing the heads of Assam’s Vaishnavite monasteries with the honorific Prabhu Ishwar, and, at other times, by audacious acts like climbing poles to reach his audience in open fields. And yet, he was someone whose death was mourned on every street of Assam by hundreds and thousands of people from every walk of life — rich, poor, old, young, insiders or outsiders to the definitional orbit of Assamese — cutting across the state’s multiethnic population. Such a figure is not a regular singer for sure.

Zubeen became the quintessential singer for the emerging Assamese middle class that aspired to be like their counterparts elsewhere at the turn of the century. But unlike in most smaller Indian cities and towns, where liberalisation had opened up opportunities for a new middle class, as political scientist Leela Fernandes writes, this potential class in Assam and Northeast India found itself wanting and waiting to have access to the material culture that defines the identity of the middle. In the latter’s absence, the limited visual media, audio gadgets, and music cassettes became much more than mere entertainment. It became their sustenance.

But can music alone replace or replenish such aspirations? Perhaps the answer was yes, for Assam (or for Shillong) at least in those days. In Zubeen’s voice they found not just melody or poetry but a meaning for life — a way to approach their dreams when avenues remained scarce. The extraordinariness of Zubeen was that he eventually transcended the boundaries of his own middle-class upbringing and that of his fans.

But what made him a mass cultural icon? Perhaps a raw, untamed talent that didn’t require any grooming, godfathers or gharanas. Zubeen came to the stage at a time when the greater Assamese society was torn apart by conflicting emotions seemingly unsuitable for music. People were unsure whether to stand with the sons of the soils who had taken to the forests in search of freedom or with the brutal armed forces that came from Delhi in the name of restoring peace in the region. His songs gave people, especially the younger generation, the rhythm of love, hope for change, and a bridge to Bollywood music and Western pop through local lyrics and tunes. He delivered successive hit albums with Anamika, Maya, Asha, Mukti and Pakhi. These songs were about freedom, love, existential threats, precarity of life conditions, and belonging.

Zubeen did not have an easy entry into the cultural world of Assam. In his early days, he was a stranger who could be heard but not be taken seriously as an artist; he was certainly not to be emulated like Jyoti Prashad, Bishnu Rabha or Bhupen Hazarika — the three cultural and literary doyens who shaped modern Assamese identity. But things changed in the late ’90s, when he started singing Bihu folk songs with melodious modern tunes, rendered numerous devotional numbers of different genres, and breathed new life into some of the timeless Jyoti-Bishnu’s songs, which was missing till then. This was the time when he also started singing Kishore and Rafi songs in a soulful way.

The genius of Zubeen lies in his access to the hearts and minds of ordinary people, his rootedness in the local culture, his love for the indigenous music of different tribes, and most crucially, his selfless service to humanity. Defying the norms of today’s political culture, he fearlessly declared himself to be a socialist leftist, an unapologetic janeyu-less Brahmin and a godless singer. Still, he remained a puzzle for people — why did he, a person madly in love with trees and nature (who wanted to be as high as a eucalyptus tree), who had raised his voice against the culling of trees in Guwahati, suddenly lose his voice? Was he under pressure? What was he trying to convey when he appeared in a t-shirt inscribed with the words “killer” at the funeral procession of Bhupen Hazarika — the legend whom he deeply admired.

Zubeen wore the weight of stardom with ease, unabashedly carrying the image of a feral creative power who feared none and bowed to none. He didn’t have to assume forced generosity or humility to win people’s love and affection. It came to him naturally, without any manager for image-building. He spoke the unspeakable that often hurt conventional sensibilities, what philosophers like Roger Scruton would call “high culture”. In a world of elite and measured artistry, he remained blissfully unrefined, unperturbed by the demands of high culture.

In his death, we lost a jewel of Assam. But more than that we lost a custodian of humanity. He dreamed of, in his songs, sleeping in the depths of the ocean. Tragically, this poetic wish became brutally true on September 19. Yet his death, like himself, was not within convention. The regular legal provisions now appear woefully insufficiently to get to the bottom of the case. The chorus demanding Justice For Zubeen is still fresh — it must not be left to wither by the politics of the day, as it is increasingly threatening to do.

The writer teaches Philosophy in JNU