Opinion Why the British spared the Sunehri Bagh mosque when building New Delhi

Distancing itself from Calcutta, built emphatically as the capital of an alien power, the colonial government wanted to rework its image by the shift to Delhi. And in Delhi, by building a city that took the history of previous Indian empires as its reference points, it sought to project at least a semblance of connection with the Indian people.

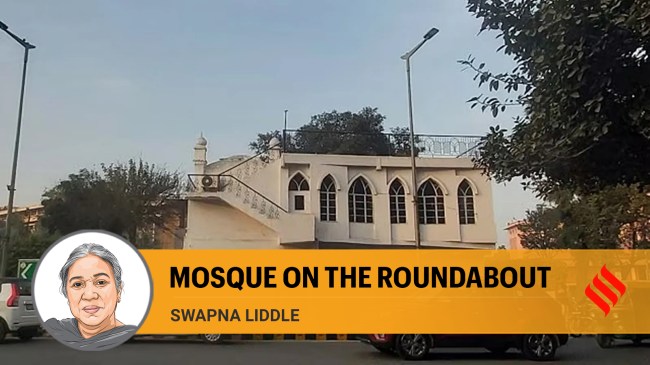

Not only did the planners of New Delhi make room for these structures, but they took this existing historic landscape as their starting point in a very fundamental way. (File)

Not only did the planners of New Delhi make room for these structures, but they took this existing historic landscape as their starting point in a very fundamental way. (File) A controversy has arisen recently, with the New Delhi Municipal Council calling for public objections and suggestions regarding a proposal to demolish a certain Mughal-era mosque in the heart of New Delhi.

A bit of historical background may be useful here, to understand how this building came to be located where it is. Till about a hundred years ago there was a major road, known as Qutub Road, which led from the north-western end of the Mughal city of Shahjahanabad (which we now call “Old Delhi”) to the Qutub Minar, and beyond to Gurgaon. Like many other highways of its time, this road had several gardens located beside it. In the days before motorised transport, when travel by road was a slow affair, these would have served as resting stages. One of these gardens was Sunehri Bagh, which had a mosque in it.

In 1912, the British government in India decided to build the city of New Delhi at and around Raisina, through part of which this road passed. The land was acquired, the population that lived there was relocated, and most of the buildings on it were demolished. While many of these buildings were the relatively recently built homes of those who had been living here, there were also a large number of older buildings — palaces, tombs and places of worship, built over the centuries. The government gave the Archaeological Survey of India the task of listing these historic buildings, with a view to identifying which should be preserved and which might be demolished.

Finally, most were cleared away, with a few exceptions. Among those spared were structures of special historical or architectural significance, such as Jantar Mantar, Humayun’s Tomb, Safdarjung’s tomb, Agrasen ki Baoli, etc. Historic significance was not the only criterion for preserving a structure. Several old places of worship were spared mainly because they were still in use. These included Gurdwara Bangla Sahib, Gurdwara Rakab Ganj, the Zabita Ganj mosque on the Central Vista greens, the Hanuman Mandir on what is now Baba Kharak Singh Marg and a couple of Jain temples across the road from it, and the mosque in Sunehri Bagh.

Incorporating these structures into the town plan of the new city required some degree of creativity. Clusters were incorporated into green areas — such as the Lodi and Syed tombs into Lodi Gardens, and a number of Mughal tombs into the Golf Course. Some major roads were aligned so as to feature these monumental buildings as focal points on vistas — Safdarjung’s tomb at the end of Prithviraj Road is a notable example. Other alignments were modified — the curve in Sher Shah Road to accommodate Lal Darwaza makes it stand out among the otherwise straight roads radiating from the C Hexagon on which India Gate stands. Stray structures were left to stand on pavements and smaller green areas. The Sunehri Bagh mosque was placed on one of the many roundabouts that were built.

This makes the Sunehri Bagh masjid of interest not only as a Mughal-era mosque, but for what its location on a roundabout tells us about the town plan of New Delhi. The street plan made up of intersecting radial roads and roundabouts was laid on land that was already dotted with historic structures. Not only did the planners of New Delhi make room for these structures, but they took this existing historic landscape as their starting point in a very fundamental way. In a speech in 1933, Edwin Lutyens acknowledged the role of the Viceroy, Charles Hardinge, in determining this aspect of the city’s plan, saying, “The new city owes its being to Lord Hardinge…His command that one avenue should lead to Purana Kila and another to the Jumma Masjid was the father of the equilateral and hexagonal plan.” So, in fact, Lutyens explained the street plan of New Delhi as an extrapolation of the triangle formed by three points — Purana Qila, Jama Masjid, and Raisina hill.

Politically, this was a statement the British government in India was making. Distancing itself from Calcutta, built emphatically as the capital of an alien power, it wanted to rework its image by the shift to Delhi. And in Delhi, by building a city that took the history of previous Indian empires as its reference points, it sought to project at least a semblance of connection with the Indian people.

Today the roundabout and the mosque on it represent the complex and layered history of the city. Moreover, this city of New Delhi (more or less coterminous with the NDMC area) has a very distinctive town plan, characterised by low-rise, low-density development, full of trees, that acts as a lung within a metropolis that faces a crisis of air pollution. This itself is a good reason to maintain the low densities and a moderate volume of traffic that is served quite well by the roundabouts.

The writer is a Delhi-based historian