Opinion Vamsee Juluri responds to Pratap Bhanu Mehta: Sanatan Dharma row and the need to ‘eradicate’

There are many haunting tales of reform emerging out of new India, that is Bharat. But disavowing one's own inheritance cannot be one of them

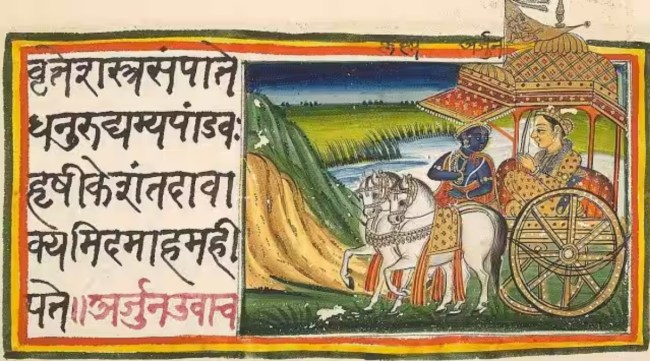

But is it enough if only people of Brahmin ancestry are thus re-educated? After all, that pernicious ideology has spread from the time of its original invasion/migration into South Asia in 1500 BCE so all Hindus must convert from Sanatan Dharma, isn’t it? (File)

But is it enough if only people of Brahmin ancestry are thus re-educated? After all, that pernicious ideology has spread from the time of its original invasion/migration into South Asia in 1500 BCE so all Hindus must convert from Sanatan Dharma, isn’t it? (File) There is a wealth of knowledge in Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s recent articles in The Indian Express. In the first one (‘We, the decolonialists’, IE, August 31), he questions the “decoloniality” claim in “Indic” writing and pares it down to a core question: How do citizens relate to each other? In the second (‘Tradition & its discontents’, IE, September 5), he defends Udhayanidhi Stalin’s speech at a conference on eradicating Sanatan Dharma by condemning his critics for failing to see the wounds calling out from his words. Stalin, he writes, “hauntingly drew attention to the moral wreckage of Indian traditions”.

The word “hauntingly” caused a kind of epiphany. I will admit it wasn’t immediate. At first, in a lower-chakra sort of way, I thought, “How can you white-wash a classic dehumanisation trope?” But then, I allowed myself to be challenged. As the unatoned depths of privilege-fragility melted, understanding came.

And specifically, it came as one image, a scene from the climax of the movie Jagte Raho (1956). Raj Kapoor’s character, an innocent man mistaken for a thief, is frantically climbing down the building. Frenzied mobs scream for his blood. Then suddenly, a rock flung at him smashes a window and he sees the greatest symbol he can find of his predicament: A figure of Jesus on the cross.

The call of the innocent man always moves the human heart. In religion, art, speech.

Most of us didn’t quite hear that call in Stalin’s words, but Mehta did. I grant him that. But “haunting” also reminded me of another movie from the same era — the charming multilingual hit Missamma (1955, Missiamma in Tamil, Miss Mary in Hindi). The story involves NTR and Savitri (in the Telugu version) pretending to be a married couple to get a job as residential tutors. Savitri’s character is Christian, but her employers don’t quite get that. In one exasperated moment, she declares her true faith and shows off her cross. Upon which a comedic visiting vaid diagnoses her illness as possession – by a Christian ghost!

In the old days, this movie’s depiction of a “lost at birth” story (Miss Mary actuallywas Mahalakshmi, the employers’ missing daughter), sufficed to affirm a popular moral position. Accepting the worship of Jesus or Allah by our fellow Indians was taught to Hindus as our virtue. But now, of course, that acceptance has been deemed inadequate.

We are told we have to “eradicate,” entirely.

How exactly will this be done? Death camps?

Trains? Snowpiercer or Soylent Green, where historically expropriated surplus is re-extracted from Brahmin bodies? Apt for having been “useless eaters,” as the Nazis and their Indian imitators used to put it perhaps. But is it legal? Professors at prestigious universities say, “Brahmin lives don’t matter… as Brahmin lives.”

Okay, that ellipsis might make death camps unnecessary. So, some simple re-education camps might suffice, along the lines of the “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” ideology which led to the mass kidnapping, torture, and religious conversion of tens of thousands of Native American children in North America till as recently as the 1970s. But is it enough if only people of Brahmin ancestry are thus re-educated? After all, that pernicious ideology has spread from the time of its original invasion/migration into South Asia in 1500 BCE so all Hindus must convert from Sanatan Dharma, isn’t it?

What will that conversion entail? That too is a haunting question. Religious conversion is one option. Progressive South Asian magazines have called Hindus to convert to Islam to show solidarity for the oppressed. And non-religious conversion is already underway for many into some kind of atheism or secularism.

But is this enough to truly declare this “eternal” pandemic over? US Vice-President Kamala Harris won an election without identifying as a “sanatani” and still was criticised for having Brahmin ancestry. An atheist Tamil Brahmin manager at Cisco was accused of casteism even after boasting of abandoning his thread and his religion. Although the case against him was dismissed, and although a Dalit-Bahujan father in California recently died while trying to stop the “eradication” bandwagon there, the state assembly has just passed SB403, which purports to eradicate, not “sanatan dharma” (as saying so might be illegal in the US), but just “caste discrimination.”

So, a serious answer to the eradication demand needs a good time frame to guide us. How many generations after eradication is it finally good enough? Susan Jacoby writes in Strange Gods: A Secular History of Conversion (2016), about the endless inquisitions and persecutions Jews in Europe faced even after conversion to Christianity. Pagans, Catholics, Heretics. Tortured, killed, taunted, for never being pure enough.

Getting people to relate to each other just exactly right is a bit difficult, isn’t it? Especially when the facts haven’t all been quite true in the first place.

That reminds me of one more story from a 1950s science-fiction comic series called Weird Science. An astronaut lands on a distant planet. He finds the people are “poor caste” while a wealthy and very religious “priest caste” rules over them. He gives the poor medicines and food. They call him a savior. The priests execute him. Then, centuries later, another spaceship arrives. What do they see? The elites now rule in the name of the same man they executed centuries ago. His torture-instrument is now the planet’s religious symbol.

A story is a powerful thing. It can inspire us to do great things.

The chief of a great nationalist service organisation recently lamented “2,000 years” of suffering caused by elites who withheld knowledge. He also shared the story of a Hindu volunteer who was served beef by a Muslim friend to test his commitment to egalitarian ideals of inter-dining. The Hindu volunteer ate it with love in his heart for his neighbour.

So many haunting tales in the new India, that is Bharat. But reform is never complete. So many temples to liberate from “greedy priests,” as the Maharashtra government is reportedly trying to do. So many more holy cows to kill, sacred books to burn, threads to use as wicks to burn them with.

A story is a powerful thing. And the last one I am reminded of here is the movie Inception (2010).

Once an idea has been put in your head it becomes your own. Especially the idea of rejecting your own inheritance.

Vamsee Juluri is a professor of media studies at the University of San Francisco