Opinion As V-P Dhankhar criticises Basic Structure, recalling what BJP margdarshak L K Advani once wrote: ‘One of law’s greatest ever triumphs’

"Law was being distorted to make Indira Gandhi like Queen of England"

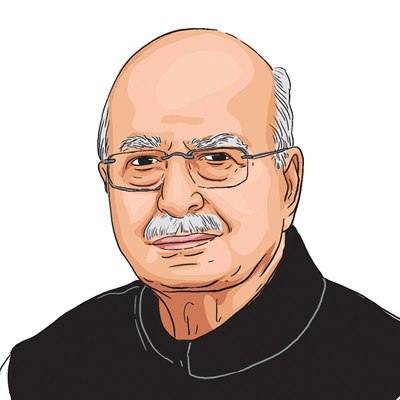

Former Deputy Prime Minister L K Advani's book 'My Country, My Life' was published in 2008. (Express Illustration: C S Sasikumar)

Former Deputy Prime Minister L K Advani's book 'My Country, My Life' was published in 2008. (Express Illustration: C S Sasikumar) When the Constituent Assembly adopted, after intensive and prolonged deliberations, the Constitution of India in January 1950, it had scarcely imagined that a day would come when the statute would be mutilated and democracy endangered by the government itself. Nevertheless, the astute and farsighted makers of the Constitution had built in many defences to ensure as a reliable shield against assaults by despotic rulers. The Prime Minister [Indira Gandhi] and her coterie of sycophantic advisors knew this too well. Hence, soon after the imposition of the Emergency, they set in motion systematic measures to dismantle, one by one, the democratic defences laid out in the Constitution.

In the very first farcical session of Parliament in the monsoon of 1975, the government got the 39th Constitution Amendment Bill passed. It made the proclamation of the Emergency non-justiciable and protected the provision of the President’s “satisfaction” from judicial scrutiny not only in the matter of Article 352 (Proclamation of Emergency), but also with regard to Article 123 (Proclamation of Ordinances) and Articles 356 (Imposition of President’s Rule in States). The Governor’s power to issue ordinances under Article 213 was similarly protected. Protection was also accorded to the power of the President to suspend citizens’ Fundamental Rights under Article 359. Clearly, the government was laying the foundation for an authoritarian state, in which the political executive (the Prime Minister) first turned the incumbent of the Rashtrapati Bhavan into a rubber-stamp, and made the rubber-stamp, and itself, unaccountable to the judiciary.

On August 7, the government introduced the 40th Constitution Amendment Bill, the strangest-ever legislation of its kind to be considered by Parliament. It aimed at preventing the courts from hearing petitions challenging the election of the President, Vice President and MPs holding the office of Prime Minister and the Speaker of the Lok Sabha. These elections, the amendment provided, could be challenged only before a special forum to be created by Parliament. The most obnoxious feature of the Bill was its fourth clause, which declared that all decisions taken by a high court with regard to the election of any of these four dignitaries would be deemed null and void! Under the cloak of exercising its amending power, Parliament had thus usurped the powers of the judiciary. Only a fascist state could have vandalised the Constitution in this manner.

On 8 August, I wrote in my diary: “In theory, the Indian Constitution was still republican. For all practical purposes, however, the law was being so distorted as to make Indira Gandhi like the Queen of England…”

The next day, which was to be the last day of the Rajya Sabha session, [H R ] Gokhale [Law Minister] produced the most outrageous of monstrosities, the Constitution (41st Amendment) Bill. By amending Article 361, it sought, in the main, to confer upon the Prime Minister immunity against criminal proceedings in just about every conceivable case. I expressed my complete outrage in my diary: “That such a measure should have been conceived is itself shocking. On the pretext of protecting the Prime Minister from unnecessary litigation, it seeks to legalise crimes committed by her or him.”

In 1976, the government introduced in Parliament the Constitution (44th Amendment) Bill which, after adoption, would become the 42nd Amendment. Apart from providing for a six-year term for the Lok Sabha and the state assemblies, it sought to drastically curtail the Fundamental Rights of citizens and make the most rapacious encroachments into the independence of the judiciary. Almost all laws and government actions were made unchallengeable in court. It also had two particularly pernicious provisions: (1) It authorised the President to amend the Constitution through an executive order for two years! (2) It abolished the need for quorum in Parliament, which meant that just two or four could make laws for the country!

This atrocious mutilation of the statute provoked me to pen another angry underground pamphlet titled ‘Not An Amendment, It’s a New Constitution’. I wrote: “The Emergency itself is phoney, and the proclamation mala fide. This apart, a Lok Sabha which has given itself an extended tenure for avowedly emergency reasons is essentially a caretaker Parliament, politically competent to undertake only routine legislation. A major constitutional metamorphosis such as this one is certainly outside its ken. The 44th Amendment Bill,” I warned, “is an undisguised bid to destroy all checks and balances built into the Constitution. Depradations are to be made into the realm of all institutions except the Executive. The upshot of this would be that the Prime Minister would become a constitutional dictator.”

The hallmark of every dictatorial regime is that it is never honest and transparent with its own people. Strange though it may sound to those belonging to the post-Emergency generation, the Congress Party at the time, under the influence of communists within the country and its supporters in the Soviet Union, was carrying on a propaganda that the main reason for India’s poverty was the constitutionally guaranteed right to property. For years, the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Golak Nath case was being flaunted as a major roadblock on the path of economic progress. This judgment, delivered in 1967, held that Parliament had no right to abrogate or abridge any of the Fundamental Rights…

Then came the 24th Amendment, seeking to undo the Golak Nath judgment. The amendment conferred on Parliament the right to amend any provision of the Constitution including those related to Fundamental Rights. The validity of this amendment was challenged. The case that ensued, the Kesavananda Bharati case, in which the verdict was delivered in April 1973, has now become a landmark in Indian Constitutional history. Drawing up a Lakshman Rekha – a thus-far-and-no-further limit – the court held that “the amending power of Parliament is wide, but limited. Parliament has no power to abrogate or emasculate the basic elements or the fundamental features of the Constitution”. Since then, this has come be known as the doctrine of the Basic Structure of the Constitution.

During the Kesavananda Bharati hearing, government counsel were put searching questions from the Bench as to what exactly they meant when they claimed an unfettered amending power for Parliament. Government counsel were brutally frank and forthright in their replies. According to them, it included the power to: (1) destroy the sovereignty of this country and make this country the satellite of any other country; (2) substitute the democratic form of government by an authoritarian form of government, (3) extend the life of the two Houses of Parliament, indefinitely; and (4) amend the amending power in such a way as to make the Constitution legally, or at any rate practically, unamendable.

The Supreme Court very rightly refused to accept this contention. It felt that this was like empowering government even to scrap the Constitution. Justice [H.R.] Khanna, whose judgement became decisive in this case, made this very crisp observation: “Art. 368 (Article relating to the amending procedure) cannot be so construed as to embody the death-wish of the Constitution or provide sanction for what might perhaps be called its lawful hara kiri.”

The government was deeply unhappy, indeed exasperated, with this judgment. The government’s annoyance with the verdict was officially proclaimed when in October 1975, A.N. Ray, the government’s hand-picked Chief Justice of India, announced that, in deference to a request made by the Attorney General of India, he had decided to constitute a full Bench of the Court to review the Kesavananda Bharati judgement…

It was at this juncture that the legal fraternity in India recorded one of its greatest ever triumphs in defence of the “Basic Structure” of the Constitution. The hero of this battle was another illustrious lawyer from Bombay: Nani Palkhivala. Before the Emergency, he had consented to be Indira Gandhi’s lawyer to argue her review petition in the Supreme Court seeking annulment of the Allahabad High Court’s verdict against her. However, once the Emergency was imposed, he courageously returned her brief and became an outspoken critic of the authoritarian regime…

In my essay, I recalled what Dr B R Ambedkar, the chief architect of the Indian Constitution, had said about Article 32, the provision comprising writ jurisdiction of courts. Speaking in the Constituent Assembly on December 9, 1948, Ambedkar commended Article 32 in these words: “If I was asked to name any particular article in this Constitution as the most important, an article without which this Constitution would be a nullity – I would not refer to any other article except this one. It is the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it.” It is this heart and soul of the Indian Constitution which the Congress government was itching to destroy.

The writer, former Deputy Prime Minister of India and president of BJP, is currently a member of the party’s Margdarshak Mandal. This is an edited excerpt from My Country, My Life (2008)