Opinion Two Sharifs, one strategic departure

Pakistan’s army chief and PM are challenging dangerous narratives that haunt and hobble the country.

The state’s view of India forms the basis of Pakistani textbook nationalism.

The state’s view of India forms the basis of Pakistani textbook nationalism.Pakistan’s ex-ISI boss General Hamid Gul said last month that he didn’t believe Osama bin Laden was killed by the US because he was already dead from poor health. He said he knew 9/11 never happened the way it was claimed and that the “Jews had done it”. Why did he say this? Because it resonated with two deeply embedded narratives in Pakistan.

VIDEO LOADING…(APP users click here to see video)

There are actually three narratives haunting Pakistan. The first is driven by the West and looks at Pakistan as the centre of international terrorism, ground zero for al-Qaeda, whose leader the US killed in Abbottabad in 2011. Pakistan was offended by the US commando action and punished a doctor who had helped locate Osama. Here, we are in a grey area of conflict — Pakistan seems to defend the killers of scores of its military personnel.

[related-post]

The second narrative is the “pan-Muslim” narrative, which quarrels with the definition of terrorism — because of Palestine and Kashmir — and justifies it as a “war of liberation”. Gul articulated the central tropes of this narrative.

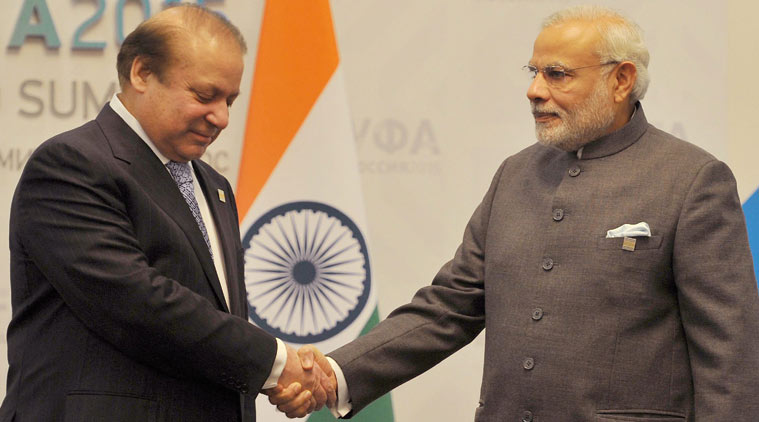

The third narrative is the state’s view of India, which forms the basis of Pakistani textbook nationalism. It perks up every time Indian politicians make threatening statements about Pakistan. The glue of nationalism thus formed is supposed to hold Pakistan together. But anyone abstaining from India-centrism runs the risk of being ostracised, including prime ministers who try to normalise relations with India through the clever indirection of free trade. This narrative is unbending and not subject to change.

The external narrative coming from the West is rational and research-based, and therefore highly persuasive. While outside Pakistan it is accepted as fact, it is effectively blocked by the other two narratives in the country. This results in the practice of isolationism in the face of anti-Pakistan postures in the neighbourhood and the world. Internal intellectual conflict also results when the external narrative, accessible on the internet, polarises opinion between those who can read English and those who read only the idiom of nationalism, Urdu.

Pakistan’s “ungoverned spaces” have grown like a spreading stain in the countryside and the mountains. Security of private property, which caused the birth of the state in antiquity, is fading in Karachi. The two internal narratives were strong enough to defend this status quo, but Pakistan’s new army chief, General Raheel Sharif, decided in 2014 to change strategic tack on the country’s “ungoverned spaces”.

The persuasion came from China, which was able to convince the new military leadership to pay heed to the creeping demise of the Pakistani state because of the terror perpetrated by Pakistan’s “non-state actors” and their international cohorts. China also persuaded Afghanistan, whose revisionist mistrust of Pakistan is matched only by Pakistan’s revisionist hatred of India, to undertake conversations of mutual understanding on terrorism.

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, after responding positively to Pakistan’s new diplomacy, has been pushed back by the Afghan Taliban, which the Afghans suspect is being operated from Pakistan. Ghani seems to have given up, saying Pakistan has imposed an “undeclared” war on Afghanistan. Suicide-bombers spearheading this new Taliban aggression are seen as coming from Pakistan, primed with funding from the Gulf Arabs.

Kabul insists, and Islamabad denies, that orders for attacks in Kabul go out from the “Quetta shura”. Taliban leader Mullah Omar is somewhere in Pakistan, if not in Quetta; no one can tell for sure. Reports from the external narrative established long ago that Pakistan could not dictate to the Taliban leadership it was sheltering.

No one loves Pakistan in Afghanistan, especially now that a decade of freedom under US occupation is threatened with a reversal to savagery. No one loves Pakistan in Iran — witness the frequent cross-border shelling — because of the routine Shia massacres in Quetta. Pakistan is fighting the Shia-hating Taliban but is yet to tackle the Taliban’s Punjabi allies that keep on killing. Needless to say, no one loves Pakistan in India.

Raheel Sharif’s army is backed fully by PM Nawaz Sharif’s government as it takes on the Taliban in the “ungoverned spaces” in the mountains and in the “partially ungoverned” cities of Karachi and Quetta, to say nothing of Balochistan. Doing this, they are partly siding with the diagnostic external narrative and challenging the pan-Muslim narrative.

But the nationalist narrative persists. It sees terrorism as a weapon of India, a misdiagnosis that will harm Pakistan in the long run. Of the ruling duo, the Sharif government is less willing to embrace this narrative and hence more likely to risk its popularity as an elected entity. The strategic departure of the two Sharifs has encouraged many Pakistani observers to think that Pakistan may finally say goodbye to its past frame of mind. But if it is reversed, Pakistan will have closed the last door on its recovery from decades of erosion of state sovereignty in the name of jihad and revisionism.

The writer is consulting editor, ‘Newsweek Pakistan’