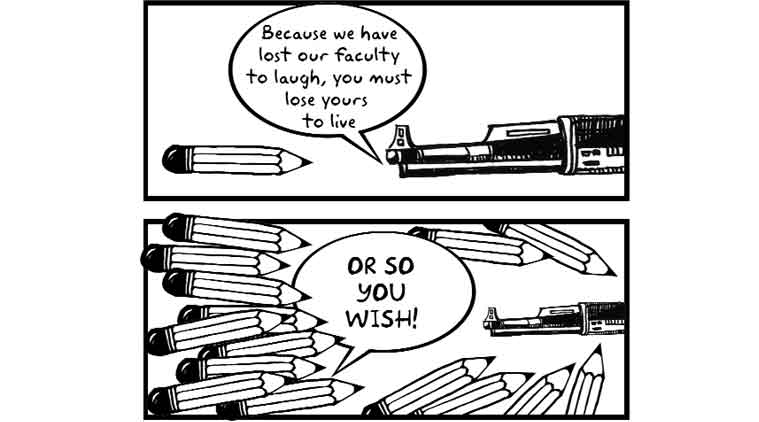

Opinion The drawing board lives

But humour is an endangered species in India. Why we need a ‘Charlie Hebdo’

(Source: Illustrated by Vishwajyoti Ghosh)

(Source: Illustrated by Vishwajyoti Ghosh)

Visiting France in 2004 for an arts residency, I was introduced to Tignous, a cartoonist who for me opened the world of Charlie Hebdo.

Over the months, I met and engaged with many Paris-based cartoonists to get a peek into the thought blurbs and speech balloons of French humour. Having been inside an editorial meeting at Charlie Hebdo and made some friends there who are now lost, it is important to understand that different cultures have different vantage points about humour itself. A day at its office made it evident that Charlie Hebdo’s mandate has always been to be the disruptor, provocateur, think-what-you-may-but-I-find-it-funny-and-I-don’t-care, and it operated pretty much from that realm.

Available across France, on every newsstand, the 12-pager comprising only political and social cartoons is well known across the region, if not well read. But then, even by French standards, a print run of 60,000 is high. The paper and its cartoonists expressed themselves within the French paradigm — as deceased editor Charb (Stephane Charbonnier) put it, “I live under French law…” But then again, freedom of expression within the law is a funny thing. No wonder, the paper, originally called Hara-Kiri, was banned and then returned as Charlie Hebdo in the same spirit.

Now that over 72 hours have passed and debates on all sides have filled our bandwidths, it is important that none justify the brutality of the act. As a practitioner, it is a given that I believe in the power of the form, its pervasive nature and a cartoon’s ability to stir. But the content is always debatable. My sense of humour could be different from yours and as long we agree to disagree, it should be fine. Do I personally agree with all that Charlie Hebdo published? No. Many of the cartoons were outrageous and in bad taste, but that’s for me, and it might not be the same for you. As a cartoonist, do I believe all Charlie Hebdos should be on the stands each morning? Yes. Yes, because it is important for the cartoon to be seen, much as it’s important to be read. My making one and your engaging with it, even just for a laugh, is critical for the form itself.

Bitter and distraught the morning after the Charlie Hebdo attack, I was looking forward to the newspapers thrown through my window. As a cartoonist, I expected a big cartoon as the day’s lead story. But I only found more of the usual.

In India, humour will soon become an endangered species. I grew up with a newspaper (the one I still read) where, at least once a week, a political cartoon would be the main lead, the first thing on the first page. That is long gone. Often it would be the second editorial on the edit page. The space for the cartoon has shrunk with the times, also shrinking the reader’s engagement with it, and humour. No major journalism award has a category for best cartoonist, designer or infographist. They just don’t seem important contributors to the rest of the profession, leave alone the reader.

We’ve forgotten how to laugh at ourselves, to have fun or make fun. From debating through cartoons we have now progressed to debating on cartoons. Take heart, it’s the same prime-time story about “Did you cross the line?” Yes, the line that has long since become a censor moves depending on the anchor’s sensibility or sensitivity. We have now mastered the art of getting hurt. Look around, we can bring down an art show, pull down a film, burn a book and it’s the 9 pm lead. There’s a mobocracy on the streets and words like “democracy” and “free speech” in the TV studio. It only took a few minutes for Parliament to ban several controversial cartoons from textbooks. Cartoons are toxic, debates difficult, and bans simple and sanitised.

Does the Charlie Hebdo shootout mean the death of the political cartoon? I pray not. The drawing board is still living, the markers haven’t run dry. But cartoons need to be taken off life support and allowed to breathe on their own. Does India need a Charlie Hebdo? If it’s for a newspaper that drives in opinions only through cartoons, if it visually provokes a debate, if it shouts that the emperor really has no clothes, the answer is a yes. The sensitivity, humour and content is always debatable, but expression through the form itself is more critical than ever.

Ghosh is the author of the graphic novel ‘Delhi Calm’