Opinion The blurred battle-lines in Punjab

Pramod Kumar writes: In an election teeming with old cynicisms, new breakaways and mixed messages, alliances may prove to be key.

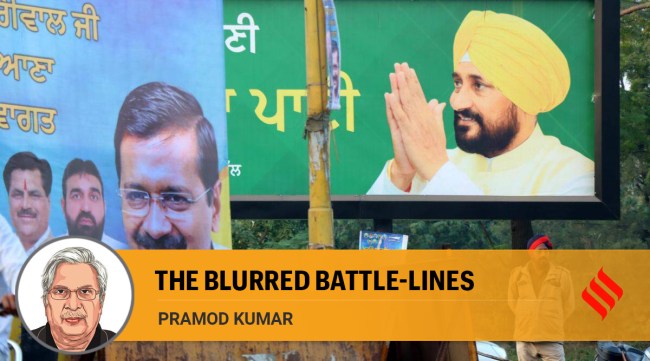

Posters of Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi and Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal, in Ludhiana. (Express Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

Posters of Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi and Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal, in Ludhiana. (Express Photo: Gurmeet Singh) A preponderance of politicians with fickle loyalties. A battle of false claims and empty promises to entice voters. Entertainment, Sidhuisms and theatrics garnished with the Delhi model of governance. The Punjab election has everything in it, except seriousness, to bring about an urgently needed paradigm shift in the state’s development path.

The election will see a three-cornered contest between the Congress, the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD)-Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-Punjab Lok Congress (PLC)-Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD Sanyukt) putting up some semblance of a fight in some targeted constituencies. The entry of the Sanyukt Samaj Morcha (SSM), a conglomerate of 22 farm organisations, may change the architecture of Punjab elections.

The new electoral alliances have ironically liberated the political parties and leaders from the shackles of ideology, principled positions and consistent normative behaviour. The BJP has entered into a pre-election alliance with the breakaway parties, the PLC and the SAD (Sanyukt). It has elevated itself as a dominant partner by contesting 65 seats — the PLC has 37, and SAD (Sanyukt) 15 seats. This alliance may not improve the BJP’s electoral performance but may adversely affect the chances of the Congress.

The SAD has not entered into an alliance with its traditional ally, the BJP, due to their disagreement on the three Acts on agriculture. It has allied with the BSP after two and a half decades. This may give an advantage to the SAD, as in the previous elections, the BSP had acted as a mega-spoiler for the SAD in over 15 seats.

There are blatant efforts to polarise Punjab on religious and caste lines, with arguments that say Punjab can only have a Sikh Chief Minister or a Scheduled Caste Chief Minister. On the contrary, multi-cornered contests and demographically different electoral alliances have evolved to place the urban Hindus and Dalits as game-changers. There are only 10 Jat-majority, two Dalit-majority and three non-Jat general category majority constituencies in Punjab. The composition of more than 102 constituencies is diverse. As a result, historically, religious and caste fault lines have tended to blur in Punjab’s electoral politics, unlike other states.

The appointment of Charanjit Singh Channi who belongs to the Ravidassia sub-caste has posed a question: Will the 32 per cent Schedule Castes continue to vote for all the political parties as in earlier elections? The answer is, perhaps, yes. Caste has been weakened at the behavioural level by the Sikh religion. Among Scheduled Castes, sub-castes like Mazhabis, Valmikis, Ravidassia and Adharmis may continue to respond differently from each other. These sub-castes are also intermeshed with the deras associated with babas or saints. For instance, a majority of the Ravidassias are affiliated with the Dera Ballan, and a section of the Mazhabis are affiliated with the Dera Sacha Sauda. So, it would be the Dera establishment that may continue to barter its support in elections. Channi may only exercise a limited influence.

Unfortunately, elections have been reduced to a ritual of democracy, as political parties promise freebies and doles and selectively target political adversaries. A party’s menu card offers something for everyone – from farmers, traders, students, Dalits, industrialists to women. The “menu-festo” replaces the manifesto which is, by definition, a declaration of principles, policies, intentions and ideological commitment. The credit for this infamous invention goes to the AAP. Divisive politics, issueless campaigns, doles and invoking religious deras — all this constitutes the subtext of this election.

Alliances are likely to be key. The SAD looks to gain from its alliance with the BSP, the AAP might be at a disadvantage due to its failure to enter into alliance with SSM. The vote share of the AAP declined from 24 per cent in 2014 to 7 per cent in the 2019 elections. Is it a sign of the decline of the AAP in Punjab? Perhaps no. There is a visible undercurrent for the AAP in many constituencies. But around 11 out of its 20 MLAs elected in 2017 and three of the four elected members of Parliament in 2019 have deserted the party. The AAP has an advantage as it has not located itself on any fault lines of caste, religion or region. The SAD has a baggage of unresolved sacrilege cases, but it has the advantage of having a regional flavour, a stable and socially acceptable leadership across various fault lines, and an experienced leader in Sukhbir Badal as compared to Bhagwant Mann of AAP and Navjot Sidhu and Charanjit Singh Channi of the Congress.

The Congress is in a self-destructive mode. Metaphorically, the Punjab Congress is divided into five Misals (to use Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s governance model) — the Sidhu Misal, Channi Misal, Bajwa Misal, Jakhar Misal and Randhawa Misal. Unfortunately, there is no Maharaja Ranjit Singh to coordinate these warring confederates. So, they work overtime to outmanoeuvre each other and are bound to adversely affect the winning chances of the party.

With the three main parties in a close contest, there are indications that Punjab is heading for a hung assembly. The margins of victory are likely to be small. It would be a political misadventure to predict the outcome in favour of or against a political party. But it can be safely concluded that in a hung-assembly-like situation, the SAD may be part of government formation — whether it includes the BJP or the AAP or even the Congress.

This column first appeared in the print edition on February 5, 2022 under the title ‘The blurred battle-lines’. The writer is director, Institute for Development and Communication, Chandigarh