Opinion Ratan Tata was a leader like no other

He took over Tata group when it was facing a crisis and shepherded it through economic reforms

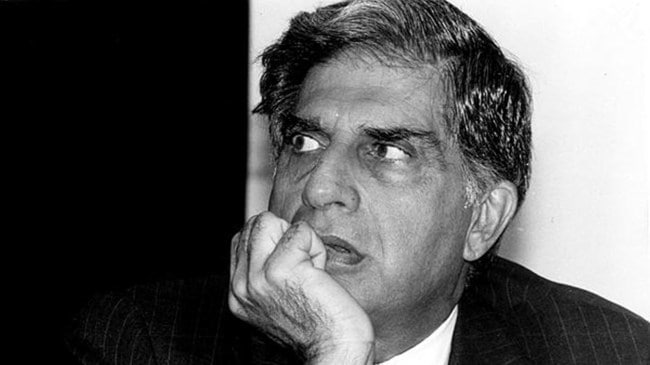

Industrialist Ratan Tata

Industrialist Ratan Tata It has been a year since Ratan Tata passed away, yet his personality continues to impact us in several ways, owing to all he did over the course of his tenure as chairman of Tata Sons and the de facto chairman of all Tata Trusts. He touched the lives of millions, uplifted families, set standards, and contributed to societal and nation-building like no other industrialist with the possible exception of the founder of the group, Jamsetji Tata. With great distinction, he helmed the group during the toughest phase encountered by the conglomerate, and he was a vanguard for the nation in its endeavour to adapt to change in a competitive world.

The sterling manner in which he shepherded the group through India’s 1991 economic reforms surpassed virtually everyone’s imagination. When he took over the reins of the group, Tata companies faced challenges that seemed insurmountable, though not many truly understood the depth of the crises.

The companies that flourished under a protective environment were thrown into the vortex of a competitive environment made more perilous by the entry of multinationals, which looked to snap up storied Indian companies. Combined with this looming danger was the urgent need to prepare companies unused to fierce competition, pull up their socks and set their house in order.

Even the group’s flagship enterprise, TISCO, later Tata Steel, was waging a war of survival that not many understood, save Tata lifers. When Ratan Tata took over as chairman of TISCO in 1993, the company was facing quarterly losses. It was faced with obsolescence of equipment, scant product spread, and a bloated workforce so large that foreign observers taunted that the company itself was unaware of the number of employees it had on its rolls. Many, including some globally reputed consultants like McKinsey, found reasons to write the steel giant’s epitaph.

The state of almost all other Tata companies was not very different. Each had its unique set of problems. Besides, there were no retirement policies for the chairman or directors, and MDs of companies virtually worked until ill-health forced them to step down, pushing most enterprises into myriad problems. The “satraps”, as they were also known, acted as if they were private owners of the companies they were running.

They were very unhappy that Ratan Tata, seen as a greenhorn, had upstaged them in the race to become chairman, Tata Sons. He faced problems across several areas. Amongst the most serious was the issue of Tata Sons’ low holding in its promoted companies. The stakes were so low that a foreign multinational did not have to muster huge resources to snap up the Tata companies because of the low holdings of the promoter in them. For instance, the Birla group held more shares in Tata Steel than Tata Sons.

The underestimation of Ratan Tata worked to his advantage. The reticent, soft-speaking chairman evolved a series of strategies to address the general problems of transformation and efficiency, and dealt with company-specific issues with equal determination. He had a plan for each issue.

At the group level, his main policies involved scaling up, modernisation, increased employment of technology, customer satisfaction, and workers’ welfare and safety. He consolidated the group, gave it a unified identity, and provided for cross-company technology and experience sharing, breaking the existing model of excellence in silos, using, for instance, the JRDQV excellence award to make companies compete with each other to improve performance and scale up efficiency. He was the first to understand the need to expand overseas, both to hedge risks and achieve inorganic growth through the acquisition of large foreign companies.

He challenged the workforce to think big and do the impossible, declaring that they should never rest on their laurels. But in all his efforts to get the group its mojo back, Ratan Tata never upbraided anyone and was never unpleasant to employees. He had the magic to tease out the best from everyone. They worked as if he were the general for whom they would lay down their lives.

The impact on the companies and group was stupendous. Under his leadership, Tata Steel, from being a moribund enterprise, became one of the lowest-cost steel producers in the world and became the first steel company outside Japan to win the coveted Deming Grand Prize. His achievements, too, were on a grand scale. He had taken the top line of the group from over $5 billion to $100 billion when he stepped down — an achievement unmatched anywhere in the world.

The unusual thing about Ratan Tata was that he was very reluctant to talk about his achievements. Very few outside the group of Tata lifers were aware of his achievements. It was his biographer, Thomas Mathew, who revealed for the first time the complicated personal life of this giant, how he overcame it, and his enormous professional achievements. As his first death anniversary was drawing near, I read the biography again. It reinforced my belief that through interviews with over 133 people across the world and a deep examination of the primary documents that only he had access to, the author has produced an outstanding work that brings out the personality of an Indian giant in all its dimensions. Ratan Tata’s life should be an inspiration to the youth for generations to come.

The writer was vice-chairman, Tata Steel