Opinion New Congress president, Mallikarjun Kharge: The pragmatic change-maker

He has the seniority to build the broadest coalition within the party and outside it as well

Kharge does not threaten anybody’s space but is shrewd enough to carve his own. (Credit: AICC)

Kharge does not threaten anybody’s space but is shrewd enough to carve his own. (Credit: AICC) Mallikarjun Kharge, predictably, has been elected president of the Congress party. He had preferred a consensus instead of a contest, but Shashi Tharoor wouldn’t relent. In any case, the contest has done a wealth of good to the party, and in general to political discourse in India.

Although the charge that Kharge was the “official” nominee of the Nehru-Gandhi family was converted into cussedness by the Tharoor camp, the contest made two opposite worldviews face each other. Tharoor represented an urban, technocratic, anglophone world that was impatient for change. Kharge symbolised old-world loyalties, rooted liberalism and an uncommon pragmatism that saw any and all change as only gradual and incremental.

While both Kharge and Tharoor are different kinds of elites, Kharge came across as penurious before Tharoor’s social and cultural capital during the campaign. This despite his long decades in the power game. The pride and prejudice that Tharoor could ignite in the public space was unprecedented. It somewhat exposed the pretensions of India’s anglophone liberals who embrace select universal values but grow blind when specifics like caste and class are placed before them.

Tharoor, during the campaign, made the exigency for reform inside the Congress party entirely about himself. He made everybody else look dilapidated and defunct. Kharge, however, was cautious and calculative about everything, including the role of the Nehru-Gandhi family. He never said they will continue to be his bosses or that he will continue to take orders from them, but he did not shy away from saying that he will actively consult them. His rationale was that they had experience and tremendous political capital which he would like to dip into. That was a wise position to take. He strategically emphasised collective leadership.

That the Nehru-Gandhis cannot be dismissed outright or overnight is a reality one has to contend with, but Tharoor was being either delusional about it or was deliberately constructing false hope for his fan base. A certain arrogance took charge of his rhetoric and made it seem like his real challenge was only Prime Minister Modi and Kharge was a token impediment.

Kharge does not threaten anybody’s space but is shrewd enough to carve his own. Those who have witnessed him operate in Karnataka without stepping on the toes of major communities and big leaders of his own community for four decades will vouch for this. His rise in Delhi since 2009 has been quite steep but has happened quietly. It is not caste alone that has put him in significant roles but his sincerity, too.

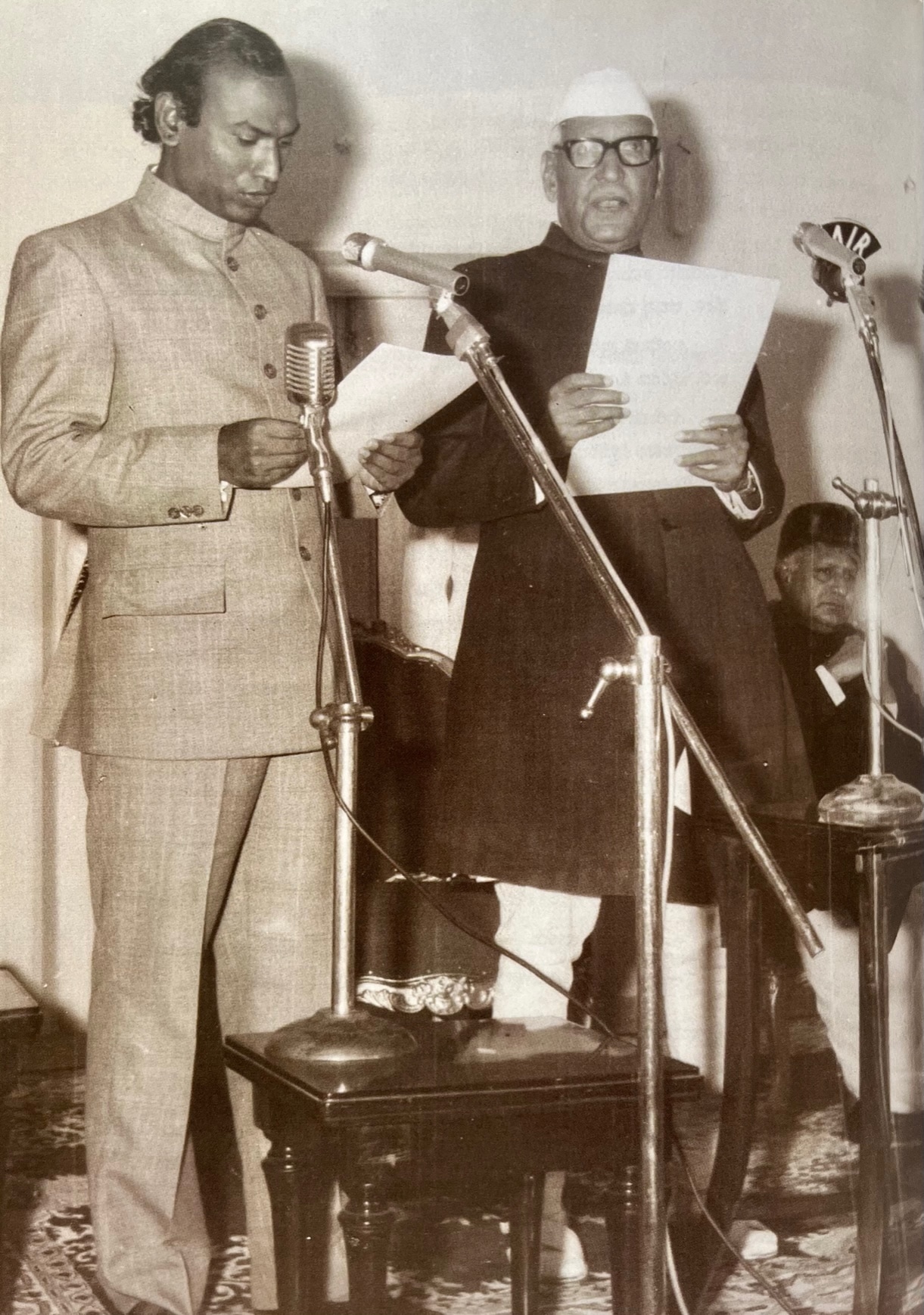

Kharge being sworn in as education minister in the Devaraj Urs cabinet for the first time in the mid-70s. Urs is seen seated behind Governor Umashankar Dixit. (Photo Credit: Samartha — a festschrift volume for Mallikarjun Kharge, edited by Dr S S Marulaiah, and published in 2005.)

Kharge being sworn in as education minister in the Devaraj Urs cabinet for the first time in the mid-70s. Urs is seen seated behind Governor Umashankar Dixit. (Photo Credit: Samartha — a festschrift volume for Mallikarjun Kharge, edited by Dr S S Marulaiah, and published in 2005.)

Kharge, a staunch Buddhist, has been an Ambedkarite since the 1960s. His early political awareness came from people like B Shyam Sunder, who spoke of Dalit emancipation in Nizam’s Hyderabad and the Hyderabad-Karnataka region that Kharge hails from. In the 1960s, Kharge was invested in the idea of growing Ambedkar’s Republican Party of India in Gulbarga. Sunder’s Bhim Sena was also a formative influence on him. The arid Gulbarga and Bidar regions of Karnataka have seen a confluence of the Lingayat and Sikh faiths that have egalitarian ideas and a casteless society as their foundational principles. Kharge has always operated against this backdrop. As a fiery labour lawyer, he was discovered by Devaraj Urs, Karnataka’s progressive chief minister, who altered the political landscape with revolutionary social justice legislations in the 1970s. Kharge was given the education portfolio in his cabinet for the first time. He hasn’t looked back since, although the chief minister’s chair has eluded him many times.

Why all this needs to be mentioned now is because Kharge was characterised as being “sycophantic” during the campaign, but he learnt early to keep his dignity and self-respect intact. To push a person like Kharge to surrender, or humiliating him, may backfire on the Nehru-Gandhis and the Congress party, not because he will rebel in his advanced age, but because of the stupendous political awakening of the Dalit community in recent decades.

Even if one assumes that the Nehru-Gandhis have sponsored his elevation as party chief, they have taken an enormous risk to do so. It is not like putting Manmohan Singh on the prime minister’s chair. Kharge’s personality is very different from past Congress presidents who were not from the family. He is not, and will not become, a D K Barooah (who famously said, “India is Indira, Indira is India”) or a quixotic Sitaram Kesri.

Kharge comes to the top job with many qualifications, yet he can aspire to be a moderate success only if he builds a broad social coalition within the party that looks at cultural, political and electoral questions independently, and harmonises them to fight the BJP.

Congress’s Dalit vote itself has become a huge question mark in recent decades. In Kharge’s own home state of Karnataka and elsewhere too, the most oppressed Dalits are inclined towards the BJP. The splintering of the community has scattered its vote preferences too. But with Kharge at the helm of Congress, at least a small number of the 200 million Dalits may rethink their preferences. That is the hope and that is a beginning for the party’s revival. He is an automatic and powerful symbol for a vast demographic. As Rahul Gandhi focuses on ideological clarity and universal values, Kharge can complement him if he focuses on electoral pragmatism. He has the seniority to build the broadest coalition within the party and outside as well.

Tharoor spoke of being the tomorrow for the party during the campaign, but with his chronic verbal excitement, he could not have functioned for a single day as the Congress party’s chief. Even a corporate house, which is largely homogenous in its composition, cannot withstand the shock of the drastic changes which he promised. It could only be like the Truss-ian promise that went bust in the United Kingdom. A complex, heterogenous organisation like the Congress party needs a humble mason instead of a loud man with a bulldozer instinct.

Tharoor would have been an ideal member of Kharge’s coalition but by constantly doubting and delegitimising the election process, he has played into the hands of the BJP. This makes his position somewhat untenable in the party. From now on, he will be the BJP’s favourite stick to beat the Congress.

The writer is a senior journalist and author of Furrows in a Field: The Unexplored Life of H D Deve Gowda