Opinion James C Scott: A scholar who went against the grain

He taught us that modernisation was not the be-all and end-all of political life, that political scientists have much to learn from anthropology and history

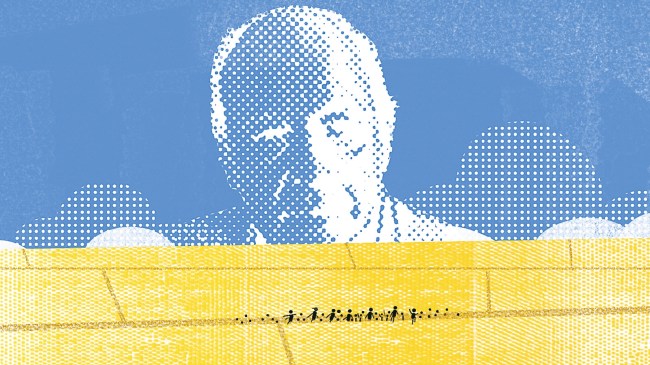

James C Scott’s lifelong interest in resistance evolved into a profound critique of state. (Illustration C R Sasikumar)

James C Scott’s lifelong interest in resistance evolved into a profound critique of state. (Illustration C R Sasikumar) A time comes — sadly, but inevitably — when a global scholar we have grown up with leaves us with a rich legacy of their achievements. We handle our grief by historicising them, by trying to make sense of their oeuvre by setting it against their lives. A similar moment of reckoning arises for me with the passing of James C Scott, the Sterling Professor of Political Science Emeritus, Yale University, on July 19, at the age of 88, a giant of a scholar whose imagination, erudition, productivity and, above all, non-conformist writings on the politics, histories, and societies of modern Southeast Asia and ancient Mesopotamia reshaped the discipline he belonged to. They also influenced scholarship beyond his discipline, including later work on popular resistance, state-making, and environmental histories.

In paying this personal tribute to James Scott — or Jim, as he was known to his friends — I cannot separate my admiration for his work from my memory of the person I first met in the early 1980s at the Australian National University in Canberra when I was still completing my doctoral studies and where Jim came to visit for a few months while working on the book that became Domination and the Arts of Resistance (1990). It was no small privilege for me, a student, to be allowed into some of the conversations that took place between him and the founder of Subaltern Studies, Ranajit Guha, also in Canberra and working, like Jim, on peasant resistance to domination. When an edition of Guha’s 1983 classic, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency, was released later in the US in 1999, it was Jim who wrote a foreword. There was something about the warmth of Jim’s intellectual personality and the open and evolving nature of his scholarship that ensured that, even though our contact became less frequent later, I never lost my feelings of friendship that were born in those months in Canberra.

What I now find remarkable about those conversations of the early 1980s was the coming together of our shared interests in both “subaltern” resistance to domination and in a variety of anarchist positions that marked our endeavours. We all valued resistance, it seems, but not the idea of a “capital R” Revolution.

For all his interest in the prospects of a peasant revolution in India, Guha never wanted a communist party to lead such a revolution. By the time we met Jim, he had already made popular his influential idea of the “everyday rebellion” of subaltern groups that he would soon introduce in his book, Weapons of the Weak (1985). He was now engaged in detailing how subaltern people create their own transcripts of resistant behaviour that are never fully transparent to the elites who dominate them. Jim’s life-long intellectual interest in resisting domination, both in his own life and in the lives of those he studied, eventually developed into a profound critique of the state — and, naturally, of the nation-state form as well. He saw the state, its “ways of seeing,” and theories of “civilisation” that were anchored in the idea of the state, as constituting an oppressive and exploitative denial of all that was mobile, unsettled, and nomadic in the history of human habitations. His last book Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States (2017), a tour de force of academic courage that took him into the unfamiliar territories of archaeology and deep history, remains a powerful indictment of everything that Jim saw as morally wrong with the political idea and the form of the state.

The Vietnam War stands as the background to all those conversations of the 1980s, prompting a global interest in peasant rebellions. In one of his autobiographical texts, Jim mentions yet another foundational influence — the French anarchist Pierre Clastres’ pathbreaking book, Society Against the State (1974). This outstanding text of French anarchism blended in Jim’s thoughts with the lessons he had learned from the Quakers of his school years, his absorption in Civil Rights movements for which he was arrested a few times, the politics of the draft, his early interest in Asian politics, and, finally, his decades-long interest in farming and sheep-breeding (he even learnt the art of shearing sheep). The result of all this was a scholar of incomparable stature who taught us that modernisation was not the be-all and end-all of political life, that political scientists had much to learn from anthropology and history, that in the capacity to defy authority judiciously lay the source of all creativity — not only in human history, but in academic life as well.

The writer is Lawrence A Kimpton distinguished service professor of history, South Asian languages and civilisations, University of Chicago. He is also a founding member of Subaltern Studies