Opinion How Gandhi crafted his own public image

His life was intimately documented, much of it by his own design

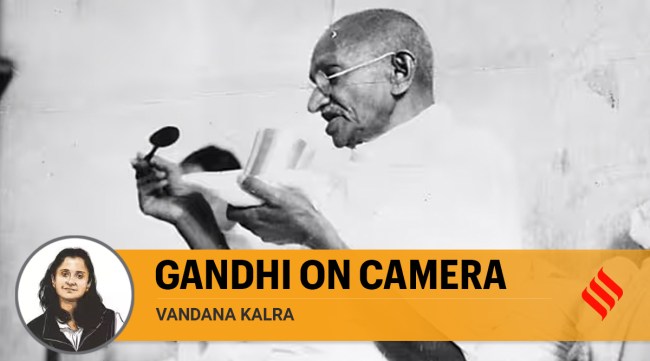

One of the 20th century's most photographed figures, Gandhi's life was intimately documented, much of it according to his desire and design. (Wikimedia Commons)

One of the 20th century's most photographed figures, Gandhi's life was intimately documented, much of it according to his desire and design. (Wikimedia Commons) On January 30, 1948, when Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated at a prayer meeting at Birla House in Delhi, there were no photographers to capture the fateful moment. French photographic icon Henri Cartier-Bresson had paid him a visit just 90 minutes earlier, and photojournalist Homai Vyarawalla had set out on her bicycle to cover the meeting but turned back. It was a regret that would stay with both photographers.

One of the 20th century’s most photographed figures, Gandhi’s life was intimately documented, much of it according to his desire and design. Realising the universal language of images, he used it carefully as a means to an end — if it helped further the cause of independence, he was willing to make his private life as accessible as his public outings. In fact, according to some accounts, an additional photo opportunity was intentional when three days after making salt at Dandi in violation of British law, Gandhi collected salt granules again at a public meeting in Bhimrad on April 9, 1930. With his son Manilal and activist Mithuben Petit standing behind him, this became one of the iconic photographs associated with the march.

Gandhi was still in South Africa when his life began to be documented in pictures, first as a practising lawyer, and later, as a proponent of Satyagraha fighting to repeal the Black Act that restricted the entry of Indians into the province of Transvaal. A photograph from 1914 shows the young leader dressed in white, mourning the death of Indian strikers killed during a police firing in South Africa. When he returned to India at the behest of social activist Gopal Krishna Gokhale, the camera followed him from the moment he disembarked with his wife Kasturba at Apollo Bunder in Bombay in January 1915.

In the following years, he allowed a chronicling of his life and work in pictures. For a brief period, he reportedly kept track of his internationally published photographs and news mentions through agencies. In his later years, he would also charge Rs 5 for autographs to generate money for the underprivileged.

What began as a more formal relationship with the camera transitioned into a relatively intimate approach by the 1930s. Swiss photojournalist Walter Bosshard recalls a conversation with the leader in his book Indien kämpft! (1931), where Gandhi told him that he had sworn never to pose for a photographer again and Bosshard could try his luck by just being around him. The resulting set of prints reveal an unguarded Gandhi — shaving, reading the newspaper, spinning the charkha, sleeping, and relishing onion soup.

The most privileged among the many local and international photographers who documented his life was, perhaps, his grandnephew Kanu, who shadowed the leader until his death. He wasn’t present at Birla House on that fateful day on the instructions of Gandhi, who had asked him to continue to work in Noakhali in East Bengal. Still a teenager when he joined the staff at Sevagram ashram in the mid-1930s, Kanu had the unique privilege of being able to focus his Rolleiflex lens on his grand-uncle at any hour. The only rules that needed abidance were no flash or asking Gandhi to pose, and that the ashram would not fund his photography. He became Gandhi’s photo-biographer of sorts who recorded the quotidian moments and momentous events, including Gandhi’s 1940 visit to Santiniketan to meet Rabindranath Tagore.

An opportunity to be able to film Gandhi more closely was no guarantee even for those considered mavericks. In 1946, when American photographer Margaret Bourke-White wanted to photograph the Mahatma spinning his charkha, she was advised to first learn to spin the wheel herself. She was possibly the last journalist to interview Gandhi hours before his assassination. Among the questions she asked him was whether he still desired to live till the age of 125 years, which he had earlier said was the full span of life. Gandhi replied, “I have lost that hope because of the terrible happenings in the world. I don’t want to live in darkness.”

Gandhi left in that moment of darkness, but as the Father of the Nation he was to live in public memory forever — through his ideas, philosophy and the photographs that immortalised him.

vandana.kalra@expressindia.com