Opinion Why the ‘heritage’ tag to Gujarat’s Morbi bridge may have done more harm than good

If this bridge was adapted to be a pedestrian walkway, rather than an attraction for crowds, who would just go to view it, or view from it, its condition would have arguably been taken much more seriously

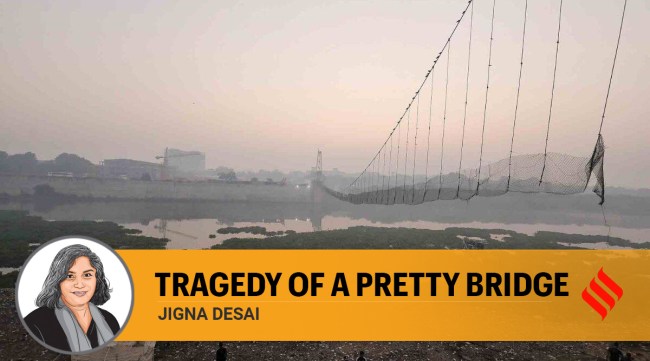

The suspension bridge collapse in Morbi killed 135 people. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

The suspension bridge collapse in Morbi killed 135 people. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran) World Heritage Week is approaching in the third week of November. During this time every year, we see a plethora of events and social media posts that celebrate heritage. It becomes an occasion to spread awareness about the cultural diversity represented by heritage sites. In India, monuments are opened up for free entry, and there are heritage walks, exhibitions and talks for citizens to be aware of their history and heritage. Over the years, with such consistent efforts, we have reached a point where valuing our collective heritage is not a sign of being conservative but is a part of progressive thinking. Most young people love a photo-op in “vintage” places. To quote a known feminist, “So we leaned in….. now what?’”

Sadly, here, I want to bring in the tragedy that occurred at the Morbi bridge in Gujarat, where many lives were lost. Leaving aside the subsequent blame game, this may be a good time to reflect upon the processes and assumptions that lead to the situation of a historic bridge collapsing without any prior indication. A standard technical process for repairing or retrofitting any infrastructure requires a thorough condition assessment, identification of the causes of degradation, structural capacity and retrofitting measures that are well-considered by experts. The actual execution then follows a process of tendering, where the work is carried out based on drawings prepared and specifications given by the experts. In a government project, there are additional measures that provide checks and balances for the design, specifications, and processes of execution. In the case of the Morbi bridge, as per many news reports, none of this was followed.

While this may seem to be an anomaly and a result of callousness and corruption, what if it is not? Would we consider the possibility that this bridge was treated as “heritage” that is to be seen and enjoyed, rather than an infrastructure that is to be used? And would we consider that like all “heritage”, the only thing that was expected of this bridge was for it to look beautiful, and attract visitors?

Let’s look at all the indicators. There was an agreement between a municipality and a business group to “maintain and operate” a “pretty” bridge. The only actions taken by the business group were to change the floorplate, redo the lighting, and possibly apply a coat of paint — all akin to a beautification project. There was no risk assessment done, drawings made, or experts engaged. This is not an anomaly as such if a structure — a road or a flyover — is low-risk. This is surely not an anomaly for heritage places. Dare I say that if this bridge was adapted to be a pedestrian walkway, rather than an attraction for crowds, who would just go to view it, or view from it, its condition would have arguably been taken much more seriously. In fact, the years of awareness campaigns have only managed to disguise our collective apathy towards historic structures and heritage places while we continue to be systematically indifferent to their value as places that make a difference to a city, town, or settlement. The previously neglected places are now, in most cases, nothing more than a spectacle to be spruced up for certain occasions.

It is time, I believe, for institutions and organisations to sit up and take notice of these processes that affect heritage places and view them through the lenses of conservation. Not revival, not retrofitting, not refurbishment, not rejuvenation, not restoration, but “conservation”. The term suggests a commitment to history, it points towards a sensitive appropriation of resources and most importantly, is done to safeguard the future of humanity. For a building or a structure, this would mean carefully mapping out historical evidence embedded therein and engaging with the question of its relationship to society and the environment. Most importantly, envisage a future for the structure, through processes of adaptation, and introduce new meanings for its transition into a collective consciousness. In the case of the bridge, it could have been done by adapting it to be a pedestrian walkway, part of the city infrastructure, and introducing technological solutions that would have resulted in innovative ways of safeguarding the structure while making it accessible.

Conservation is a constant and difficult negotiation between all the realities of a place, aspirations for the future and a human need to connect to history. Institutions like IIM, NID and CEPT at Ahmedabad which are housed in iconic 20th-century buildings are undergoing these processes. Some of the best minds are on the subject, and possibly coming out with ways that do not relegate conservation to a binary narrative of “preserve or dismantle”. In the world of constant gaze, however, institutions are choosing to keep these conversations private. Institutions that could be and have been sites of open discourse are now private thought experiments. I want to suggest that there is a price for this privacy. With all their successes and failures, these processes offer lessons for society to follow. And it may be a responsible choice to articulate these choices in the context of conservation and have these discussions in the open, notwithstanding the gaze.

The writer is professor, Faculty of Architecture, CEPT University. Views are personal