Opinion Dipesh Chakrabarty remembering Ranajit Guha: My guru, my friend

The founder of subaltern studies made us see how joyous and idealistic the pursuit of ideas could be even as we wrote and debated histories.

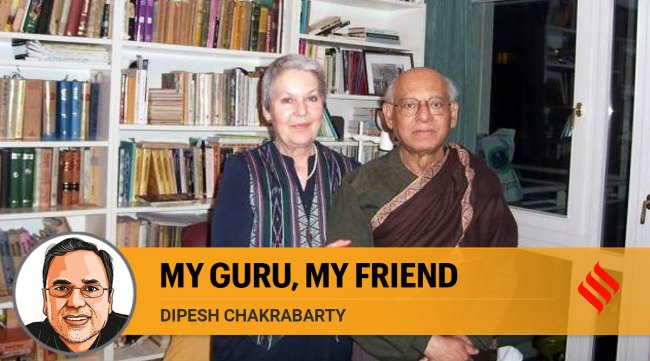

Ranajit Guha (right) with his wife Mechthild in 2008. (Photo: Nonica Datta for Permanent Black

Ranajit Guha (right) with his wife Mechthild in 2008. (Photo: Nonica Datta for Permanent Black Readers of this newspaper have already been treated to some discussion of the significance of the work of Ranajit Guha, one of the most distinguished historians of colonial and modern India who died in Vienna on April 28, a few weeks short of his hundredth birthday. This short essay is a personal tribute to the man who pioneered the writing of “subaltern histories” — histories of socially subordinated groups and peoples — and whose writings and thoughts profoundly inspired many historians and social scientists of my and later generations in India and elsewhere. Guha, however, was much more than a historian. Truly a creative intellectual, his work took several turns, as many have recounted already. Probably the last phase was the most remarkable for the surprise it created. Just as the world celebrated him as the champion of the histories of subaltern classes, he decided to stop writing in English and wrote a series of pathbreaking books and essays in Bengali that dealt with issues that were at once literary and philosophical.

In my last meeting with him on March 15 this year, he mentioned his interest in memory and time in his final decades. Life is about what engages you, he said, using the Bengali word for enthusiasm (utshaho), and added something to this effect: “Whatever engages you becomes memory and gives life its temporal dimension.”

Ranajitda and his wife Mechthild, an anthropologist, came to the Australian National University in 1980 when I was a doctoral student. My supervisor, D A Low, was instrumental in creating a position for him. I had met Ranajitda the year before in England and had been inducted into what became the famed circle of “Subaltern Studies.” Ranajitda and Mechthild spent the next 15 or so years in Canberra. That was when I had the privilege of getting to know him closely as a scholar and a human being.

In fact, one could not separate the two. Ranajitda was not required to offer any courses. What I learned from him was mostly learned in informal settings, over long walks around Lake Burley Griffin that laced the campus, over cups of coffee or lunch at the university, or over delicious meals that Mechthild — and sometimes Ranajitda himself — prepared. It was very special when Ranajitda himself was the chef. He was as meticulous in his cooking as he was in his writing. Nothing was rushed. He might spend the whole day in the kitchen following some delicate recipe for a delectable Bengali dish. There was something remarkable about Ranajitda’s relationship to time. He refused to be rushed. When academic lives all around him were getting more and more frenetic, he made sure he never had more deadlines than he could manage without getting stressed, so that he could give his writing all the care and time it needed. In this respect, his life was a standing critique of the overwhelming sense of acceleration that was taking over academic lives as digital technology began to unleash its powers.

It was not surprising then that the Socratic method was a large part of how he taught. He was both a teacher, a guru, and a friend who took a deep interest in my everyday life. I remember the day my son was born. When I called him from the hospital to give him the news, he told me that he had already thought up a name for my son, a name that my son will bear all his life. Warm and affectionate, he was also capable of strong dislikes and disagreements. Most of all, however, he loved a good argument. But if you conceded too quickly, he would object in a friendly show of disappointment as though a game had ended much sooner than the scheduled time! “You can’t give up so quickly,” he would say. “Find an argument you can defend for longer.”

Ranajitda was undoubtedly a very creative historian. But the purely empirical and time-and-place-bound nature of historical arguments did not satisfy his quest for understanding the human condition, which is why, I think, he turned towards literature and philosophy in the last phase of his writing. But his philosophical interests were obvious even as we worked on subaltern history. He would often say to us, “you can’t read a thinker on his or her own, you have to read backwards and read the people they were reading.” So, to read Marx, you had to read Hegel; to read Derrida, you had read Heidegger; to read Foucault, you needed to get back to Nietzsche, and so on, till you got to the fundamentals. My personal copy of Hegel’s shorter Logic is still the one that he gifted me, his name signed in Bengali in his beautiful hand on the title page.

Ranajitda made us see how joyous and idealistic the pursuit of ideas could be even as we wrote and debated histories. Idealistic, because it took time, hard work, and concentration to master difficult ideas. Joyous because the effort lets you discover how globally influential texts often constitute long traditions of thought within which we debate our contemporary questions. If work in the humanities is an unending series of conversations with our intellectual ancestors, Ranajitda will remain one such ancestor for years to come.

The writer is Lawrence A Kimpton distinguished service professor of history, South Asian languages and civilizations, University of Chicago. He is also a founding member of the Subaltern Studies