Opinion Dalits denied temple entry in West Bengal busts the myth of a casteless state

What distinguishes Bengali society is not absence of casteism per se but the invisibility of caste in public life. Observers tend to confuse this invisibility with its absence

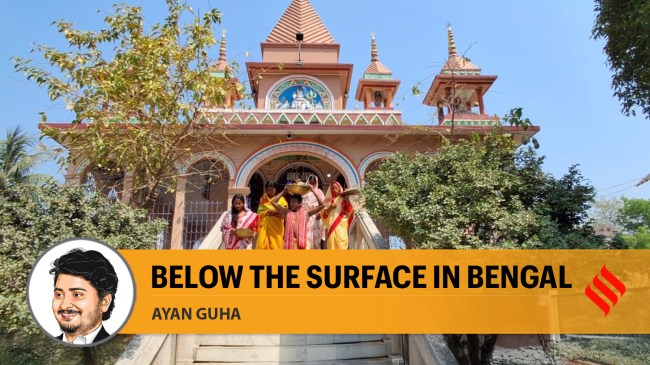

Heavy police protection outside the temple in West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district as members of a Dalit family offer prayers. (Express Photo: Partha Paul)

Heavy police protection outside the temple in West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district as members of a Dalit family offer prayers. (Express Photo: Partha Paul) One of the widely prevalent and hegemonic notions peddled by the Bhadralok, West Bengal’s enlightened upper and middle classes, is that the state’s social life is “casteless” and therefore “exceptional” compared to other states. This sense of distinctiveness has become intrinsic to the Bhadralok’s portrayal of modern Bengali identity. However, the recent denial of entry to a Dalit group into a local Shiva temple in a Burdwan village again brings into question the notion of West Bengal’s exceptionalism. This is not a one-off incident. In 2001, a Pratichi Trust survey revealed that in some schools, Scheduled Caste (SC) students were forced to sit separately. In 2004, a few newspapers carried stories on higher caste parents’ objection to their children eating cooked meals prepared by the SC volunteers.

All these incidents suggest that though caste discrimination is not a major public issue, caste still remains a reality in Bengal’s everyday life. What distinguishes Bengali society is not absence of casteism per se but the invisibility of caste in public life. Observers tend to confuse the invisibility of caste with its absence. The invisibility of caste is an expression of a casteism of a different kind, which, despite being deeply entrenched, disguises itself into inconspicuous forms. To make sense of casteism in Bengali society, one needs to unpack this curious invisibility of caste.

The hyper-invisibility of caste in Bengal is an outcome of the Bhadralok’s hegemonic social position. The Bhadralok, primarily, if not exclusively, belonging to the higher castes, were a product of the 19th century Bengal Renaissance. Being the earliest beneficiaries of western education and modernity by virtue of their advantageous caste position, they ended up acquiring the hegemonic power to define the legitimate norms of social and political behaviour. After independence, they emerged as the intellectual driving force of the class politics of the Left, which de-legitimised the lexicon of caste in the name of secularisation of the public sphere. This obscured the caste dynamics of Bhadralok dominance. As a result, though power relations are segregated along caste lines, sustained social dialogue on everyday experiences of caste remains absent, precluding the emergence of an effective and powerful Dalit counter-culture.

Heavy police protection outside the temple in West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district as members of a Dalit family offer prayers. (Express Photo: Partha Paul)

Heavy police protection outside the temple in West Bengal’s Purba Bardhaman district as members of a Dalit family offer prayers. (Express Photo: Partha Paul)

Such a scenario allows the practice of different forms of everyday casteism with impunity, inflicting symbolic violence. One such form of everyday casteism manifests in frequent use of casteist slurs like chamar and chotolok. The fact that most people use these words quite casually, often being unaware of their casteist connotations, goes to show the extent to which casual casteism has become normalised in Bengali society. It is true that caste riots are not frequent occurrences in Bengal. But when caste violence takes place, it is conveniently presented as a law-and-order problem. It is only recently that the researchers have started to explore the casteist angle of a forgotten chapter of history — the merciless massacre of Dalit refugees in Sundarban’s Marichjhapi, allegedly by police and Left cadres in 1979.

However, the most potent form of casteism is embedded in the persistent attempts by the higher-caste-dominated power structure to block all avenues of social mobility for the lower castes. For instance, the Dalits have remained abysmally under-represented in the West Bengal Assembly and Cabinet for decades. Moreover, the dominant disposition towards reservation remains overwhelmingly negative. Opposing the identification of the OBCs (Other Backward Classes) on the basis of caste, Jyoti Basu, then chief minister, submitted before the Mandal Commission that West Bengal has only two castes: rich and poor.

In 1994, the Left Front government grudgingly implemented a meagre five per cent OBC quota in government employment, which was later raised to seven per cent. Currently, OBC quota in West Bengal is 17 per cent, much lower than Mandal Commission recommendation of 27 per cent. Still, caste-based stigmatisation of beneficiaries of reservation is quite pervasive. Terms like Sonar Chand (golden moon) and Sonar Tukro (piece of gold) are widely used to demean the SCs and STs (Scheduled Tribes). In 1992, Chuni Kotal, a Vidyasagar University student and first woman graduate from the Lodha tribe, died by suicide, subjected to casteist humiliation by one of her professors. In the recent past, even a well-known professor of Jadavpur University, Maroona Murmu, got trolled online over her tribal identity.

In the literary and cultural worlds too, Dalits face exclusion. Bengali Dalit literature as a movement emerged in the 1990s, much later than its counterparts in other parts of the country and is still jostling for attention in the Bhadralok-dominated space. While a few Bengali Dalit writers have gained recognition, the readership still remains limited due to the reluctance of mainstream publishing houses to publish their writings.

The invisibility of caste in West Bengal is a complex story woven with intricate plots and subplots. The key to comprehending such complexities lies in acknowledging that, whether as villains or not, the central protagonists of this story are certainly the Bhadralok, the high priests of Bengali culture.

Ayan Guha is a British Academy International Fellow at the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, UK. He is the author of The Curious Trajectory of Caste in West Bengal Politics: Chronicling Continuity and Change (Brill, 2022)