Opinion Beijing’s trade war response: More bonds, new tools and warnings of tough times ahead

A recent Politburo meeting stressed the importance of 'stabilising employment, enterprises, markets, and expectations'. But what does this mean in tangible terms?

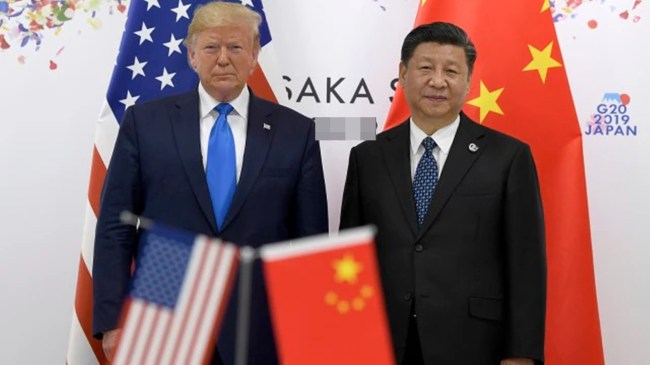

US President Donald Trump with Chinese President Xi Jinping. (Source: Reuters)

US President Donald Trump with Chinese President Xi Jinping. (Source: Reuters) The Politburo of the Communist Party of China met last week to discuss the state of the country’s economy. Dealing with the effects of the trade war with the US occupied top priority. The readout issued after the meeting offered significant clues on the future direction of policy, particularly the framing of the issue and the fiscal support that one can expect for the moment.

The official report of the meeting deployed the language of “struggle” to describe “international economic and trade” issues. This is indicative of a shift in ideological approach and perception in terms of the severity of the challenges of the external trading environment. Such a framing of the issue is also a mobilisational tool for the Party. Implicit in the notion of struggle is the idea of contradiction — a fundamental conflict between two ideas or forces — which must be resolved for history to progress. Doing so will entail challenges and require sacrifices.

In that sense, the concept also sends a message to the Chinese people that tough times are ahead. It is within this context of the concept of struggle that one must view writings in China that term the US tariff hikes part of a “protracted war” or comments by officials that cast Chinese pushback as existential and in the interest of the world at large.

In regard to specific economic policy implications of the tariff war, the Politburo meeting stressed the importance of “stabilising employment, enterprises, markets, and expectations”. But what does this mean in tangible terms?

First, there is a greater urgency in issuing local government bonds to meet the growing spending requirements. The Politburo meeting called to “accelerate the issuance and use of local government special bonds and ultra-long-term special government bonds.” For 2025, the target for local government special-purpose bonds was set at 4.4 trillion yuan, up 500 billion yuan from 2024. This fund is earmarked to be used for major regional strategies, developing new quality productive forces, and promoting high-quality development. The target for ultra-long special treasury bonds has been set at 1.3 trillion, up 300 billion yuan year-on-year.

Out of this, 800 billion yuan is planned for the implementation of major national strategies and security capacity-building in key areas, and 500 billion yuan for large-scale equipment upgrading and the continuing consumer goods trade-in programme. Already, in Q1 2024, local governments have issued 1.24 trillion yuan worth of special and general bonds, an increase of nearly 60 per cent from a year earlier. Likewise, the issuance of this year’s ultra-long-term special bonds started in April, nearly a month earlier than last year.

Second, the Politburo also called to cut key rates in a timely manner to “maintain ample liquidity, and strengthen support for the real economy”. It also demanded the creation of “new structural monetary policy tools” and “new policy-based financial instruments” to support technological innovation, expand consumption, and stabilise foreign trade.

The last key cut by the People’s Bank of China of the reserve requirement ratio was in September 2024. The average RRR (Reserve Requirement Ratio) for China’s financial institutions now stands at 6.6 per cent. So, there is room for the central bank to further slash rates in the future. In terms of new policy instruments to expand consumption, measures have already been announced to expand tax refunds that tourists can avail.

Additionally, the country’s top planner, the National Development and Reform Commission, has said that new “measures will be adopted to boost service consumption, improve eldercare services for disabled seniors, stimulate auto sales, and establish skills-oriented wage distribution systems.” In addition, the Politburo has indicated that steps would be taken to use pension re-lending to support consumption.

Third, the Politburo meeting report talked about the integration of domestic and foreign trade. Additionally, it called for increasing the income of low and middle-income groups and clearing restrictive measures in the consumption field at the earliest. How China expands consumption will be the key in dealing with the impact of the tariffs. This is also critical from an employment and social stability perspective. Roughly 20 per cent of the Chinese workforce — around 180 million people — is estimated to be engaged in export-oriented jobs. If one were to assume that all of China’s exports to the US, around 3.7 trillion yuan in 2024, were to cease, then these goods will need to be either directed elsewhere or consumed domestically. If this is not possible, there will be job losses.

China’s domestic retail sales amounted to 48.78 trillion yuan in 2024. So this consumption would need to expand by around 7.6 per cent in the extreme scenario. Practically, however, the percentage of goods impacted will be far lower. The year-on-year expansion of retail sales in China from 2023 to 2024 was around 3.5 per cent. In the first quarter of this year, retail sales have grown by 4.6 per cent year-on-year. The first quarter, however, is usually strong, owing to Spring Festival holidays. Sustaining this momentum is what will be required. Doing so, however, will entail a lot to be done rather quickly, and for greater demand-side stimulus measures.

The Communist Party, however, has largely been averse to these, viewing them as welfarism. What’s needed are immediate expansion of disposable cash and strengthening of consumer confidence. One key to this is the real estate market. If the real estate market begins to stabilise, then there is likely to be some certainty among people to spend further. But thus far, there are few indicators that the Chinese leadership is looking to strengthen support for the property market.

Finally, although the Politburo meeting did not announce any specific stimulus, the measures that were mentioned will require far more spending in the months ahead. It, therefore, seems inevitable that the fiscal deficit target of four per cent of GDP that was set in March will be overshot. For instance, the Politburo meeting report called to adopt several measures to help enterprises in difficulty, strengthening financing support for these entities. Specifically, it called to expand the proportion of unemployment insurance fund refunds for those enterprises that are “greatly affected by tariffs”.

The important point to note here, however, is that while spending is likely to expand, revenue is shrinking. China’s fiscal revenue in 2024 grew 1.3 per cent from a year earlier, slowing from a 6.4 per cent rise in 2023. Tax revenue fell 3.4 per cent in 2024, while non-tax revenue surged 25.4 per cent. Even in 2025 Q1, China’s government spending grew 4.2 per cent year-on-year, but overall revenue fell by 1.1 per cent. This resulted in the fiscal deficit reaching 1.26 trillion yuan, the highest first-quarter reading on record. Breaking down the revenue in Q1 2025, while tax revenue fell 3.5 per cent, non-tax revenue expanded 8.5 per cent. This non-tax revenue comprises land use rights sales revenue — which is falling owing to the real estate sector policies — and fees and fines, among other things. The fees and fines, however, undermine private sector confidence, which Beijing wants to boost. It is, thus, evident that Beijing faces a catch-22 kind of situation.

The writer is chairperson, Indo-Pacific Studies Programme, Takshashila Institution