Opinion The battles of Bishan Singh Bedi

It is Bedi the rebel captain, Bedi the seeker of justice and Bedi the voice of the marginalised that he would want people to remember even more than his on-field accomplishments

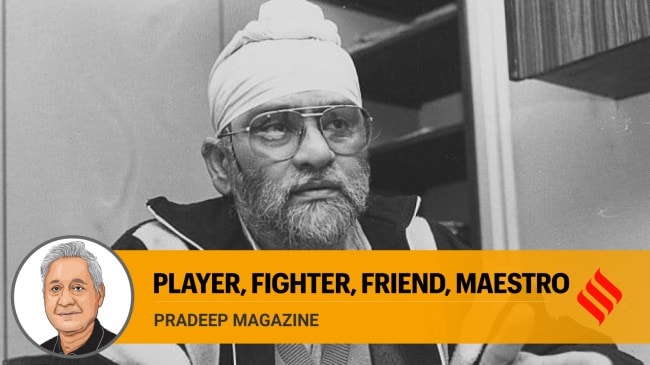

Bishan Singh Bedi’s loud and generous laughter while he narrated, with humour and care, his unending treasure trove of anecdotes, will continue to ring in the ears of those fortunate enough to have known him well. (Express Archives)

Bishan Singh Bedi’s loud and generous laughter while he narrated, with humour and care, his unending treasure trove of anecdotes, will continue to ring in the ears of those fortunate enough to have known him well. (Express Archives) Bishan Singh Bedi combined in him many diverse traits that make him a rare, colossal figure in our sporting fraternity. He was a giant among us, a man who loved a good fight and would battle to the end regardless of what the consequences could be.

Generous to a fault, yet never meek — in the middle of a difficult, unequal fight, standing up to the might of errant sports administrators, he would cloak himself in unbending steely resolve. A resolve whose nourishment came from his deep spiritual roots. Right from his childhood in Amritsar, when his father had introduced him to the Guru Granth Sahib, to the end of his journey today, he was essentially a believer who had strayed onto a cricket field.

His two lifelong companions were a cricket ball and his “Sikhi”, which, as he put it, taught him to never give up and “fight for the just rights of his fraternity.”

The craft he purveyed required a subtlety that could be mastered only through great discipline of body and mind. Never shy of taking a dig at himself, he would remember with great delight how flabby he was as a child and how his friends would say “Look, football is playing football” when he would play the game. He shifted to cricket and right from the day he bowled for the first time and uprooted the stumps of a more reputed batsman, Bedi had found his calling.

The flabby child grew up to become one of the greatest spin wizards of the game, an iconic figure whose control of the spinning ball, the variations of speed, line and length and the fluidity of his action inspired many writers to go lyrical. I remember watching him in a North Zone versus England match in 1974 in Amritsar, and wondering why were the batsmen finding it so difficult to play his innocuously tossed-up deliveries. So simple was his execution of a very difficult craft that the batsmen were literally lulled into a sense of false security. The maestro slowly and steadily entangled the batsmen in a web of deception from where the only escape route for them was to the safety of the dressing room.

He never talked about his own skills and how he honed them but he loved to talk about the greatness of others, especially his legendary spin colleagues, Prasanna, Chandrasekhar and Venkat “Without them, I was nothing,” he would say. He loved it when a batsman would hit him for a six. He would chuckle and say, “I would clap when a batsman would hit me outside the ground.” The clap meant Bedi was succeeding in letting the batsman think he had the upper hand. They were doomed after that.

Once, the great Barry Richards came out to bat against him in a county match in England, where Bedi played for Northamptonshire for many years. “I played on his ego. Packed the inside cordon, which incensed him so much that soon enough he played an indiscreet stroke and got out,” he would recall.

The genius of Bedi the bowler is strewn with many such stories that make him the most loved and admired spinner the world has seen but the Bedi story does not end here. It is Bedi the rebel captain, Bedi the seeker of justice and Bedi the voice of the marginalised that he would want people to remember even more than his on-field accomplishments.

Among the legion of battles he fought and the accusations he faced, he felt the most hurt when he was dropped and removed as the Northamptonshire captain in the year 1977. It hurt him immensely that the MCC accused him of chucking, post the Vaseline affair, when Bedi had charged England pace bowler John Lever of applying Vaseline on the ball in the Delhi Test match. The Englishmen did not forgive the humiliation of being called cheats and the establishment in England reacted by dubbing one of the finest bowling actions ever known to the cricket world as being “impure”.

He was not new to controversies nor to facing the wrath of the administrators, who feared his fearless voice, on the cricket field or outside of it. In the 1977-78 series in the West Indies, where his team chased the then world record of 404 runs to win a Test match, his batsmen were treated to a barrage of short-pitched deliveries. Fearing serious injuries to his tailenders, Bedi made a bold statement and declared. He went public in his criticism as keeping quiet was not in his character – what is wrong was to be expressly stated.

In Pakistan, he withdrew his batsmen from a one-day game in protest against umpires who were not calling short pitched deliveries as wides. But his greatest battles were fought on the home pitch. Be it for better amenities for the players who represented India or Delhi or for the wider community of sportsmen, which included Arjuna awardees. He was not a political animal but the hounding out of Sikhs in Delhi in the 1984 riots and the treatment he himself got riled him up a lot.

He may have been angry or upset with many things, yet he fought all his battles with a sense of gratitude for what life had offered him. He was the soul and wit of any gathering. Bedi’s loud and generous laughter while he narrated, with humour and care, his unending treasure trove of anecdotes, will continue to ring in the ears of those fortunate enough to have known him well.

The writer is author of two books, Not Quite Cricket and, more recently, Not Just Cricket, A reporter’s journey Through Modern India