Opinion And the hawks have it

Nawaz counted on Delhi appreciating his flexibility, without looking capitulatory at home. It didn’t work.

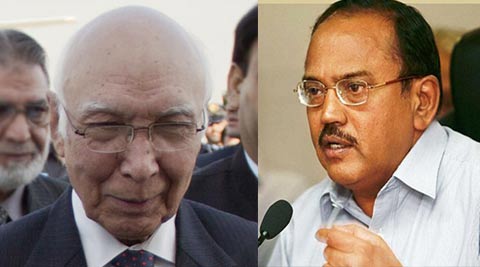

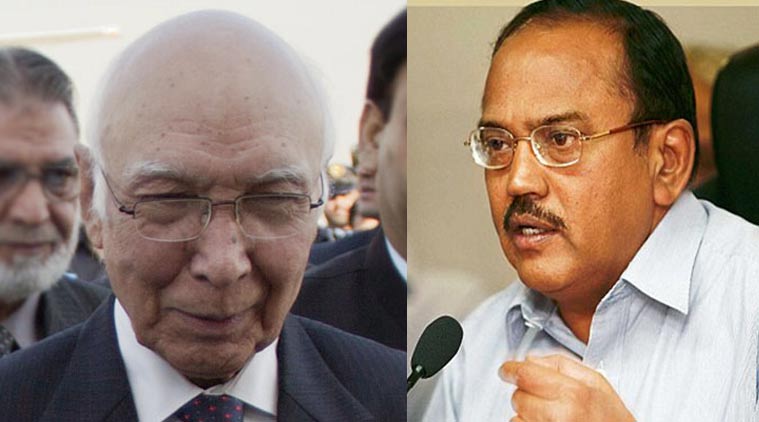

Pakistan NSA Sartaj Aziz and his Indian counterpart Ajit Doval.

Pakistan NSA Sartaj Aziz and his Indian counterpart Ajit Doval.

The August 23-24 meeting between the national security advisors of India and Pakistan, Ajit Doval and Sartaj Aziz respectively, had to be cancelled after Islamabad and New Delhi exchanged challenging statements on why it couldn’t be held. India said Aziz couldn’t meet the Hurriyat leaders from India-administered Kashmir before meeting with his counterpart, implying that the meeting would somehow undermine India’s position on Kashmir. Pakistan couldn’t do without meeting the Hurriyat leaders, although one has seen that happen without affecting the bilateral dialogue at whatever level. An empty gesture of the past has suddenly taken on significance. Precedents hurt when you want to change the game.

There was an earlier, top-level India-Pakistan meeting in Ufa, Russia, which had set the tone for what happened to the NSA-level meeting that was suggested by Delhi after it cancelled an earlier meeting. Retired military officers hogging Pakistan TV discussions on Islamabad’s India policy lost their cool on the way Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif had met his Indian counterpart in Ufa. Already tense from what the Indian army was doing on the Line of Control and the regular boundary, the audience swallowed the opinion that India was in a rejectionist mode, firming up PM Narendra Modi’s standing with an angry anti-India public opinion. The media fed on it and Nawaz Sharif was hauled over coals even for the kind of joint statement issued after Ufa. “Kashmir was not mentioned” took the field in Pakistan, and everyone who could go on TV to blow his top over it, did so.

The Ufa statement had mentioned bilateral issues in general, but terrorism was highlighted in what India then started calling the “operative part”. Nawaz Sharif had made a gesture to Modi in the statement that was generally interpreted negatively back home except by a few who understood the spirit behind it. One hoped that Delhi would grasp the gesture and be mollified, even given the roster of complaints nursed by Modi’s rank and file with an eye to Doordarshan debates. Predictably, Delhi ignored the gesture of a beleaguered PM based on the Indian wisdom that if the army is in control, why have any truck with an elected leader clearly wanting to be soft. But in the India-Pakistan arena, people are more interested in showing muscle than even obliquely considering peace.

Nawaz Sharif had counted on Delhi appreciating his “incremental”, flexible approach to India, without looking capitulatory at home. But it didn’t work either with India or at home. His handshake with Modi on the latter’s investiture didn’t go down well with public opinion, already in a warlike crouch after hearing about Indian shelling across the border killing two-three civilians every time. (Indians, too, have to react to news of cross-border terrorist penetrations from Pakistan, rendering the situation confusing to the outside world.) Add to that the action taken by Indian troops against protesting Kashmiris in Srinagar on a daily basis, and you have Muslims in Pakistan unrealistically bristling with nuclear-tipped jihad.

The post-Ufa situation was tempting. India had cut itself off from past practice, disallowing the Pakistan delegation’s meeting with the Hurriyat leaders and it didn’t want to let go of it. Pakistan couldn’t let go either of a meaningless decades-old ritual that had yielded no dividends except a hardening of attitudes in an Indian establishment that told the world Kashmir was troubled because the Hurriyat was propped up by Pakistan through all kinds of assistance, including cross-border violations.

It was media murder. Many opinion-makers who can’t resist appearing on TV rang me to ask why Pakistan is obsessive about Kashmir when no one in the world wants it to go to Pakistan, even if conscious of what India is doing to the Muslims there. They were faced with the same kind of situation as Nawaz Sharif — sick of having to carry the baggage of Kashmir, while he actually wants to do business with an Indian counterpart he had heard wanted to put business and trade on the front-burner. It was unpleasant to see the discussions on TV as some anchors tried to suck up to the hawks by proposing all sorts of punishments for the “renegade” PM. So, Aziz ended up making the ultimate show-stopping reference to Pakistan’s bomb, winning an approving nod from A.Q. Khan.

India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj made political capital out of interpreting the Ufa statement as disallowing Pakistan to pronounce the word Kashmir and meet Hurriyat leaders “before” the NSA-level meeting. She meant Pakistan was supposed to discuss terrorism only, ignoring the fact that Kashmir was strictly a part of the comprehensive bilateral dialogue that has been taking place off and on without getting anywhere, but which was the big fig leaf that allowed the two enemy states to unobtrusively embark on the normalisation of relations through trade and overland routes not opposed by any of Pakistan’s “external friends”. The NSA-level meeting was a precursor to that bilateral process which the world would have approved and the quarters inside Pakistan opposed to it could have done nothing about.

The Congress coalition could not talk because it was weak; the BJP cannot talk because it is too strong. All the cards on terrorism were with Delhi. The entire world is with India on terrorism, including most of Pakistan, which wants its army to finish off the non-state actors who indulge in terrorism, knowing full well that some of these actors are self-produced. The Pakistan Peoples Party government wanted to lean on India to get things right in Pakistan. The Muslim League thought it would do the same. It didn’t know that it would be kicked from the wrong quarters. It probably relied too much on the precedent established by an earlier Indian PM, Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

The writer is consulting editor, ‘Newsweek Pakistan’