Opinion Adoor Gopalakrishnan, caste and cinema: A reckoning in Kerala

His comments on state support for SC, ST and women filmmakers reflect a deeper problem. Malayalam cinema, like many 'cultural' fields, remains an upper-caste bastion where dominant narratives are perpetuated, certain ways of seeing and knowing are universalised, and all other perspectives and histories are buried

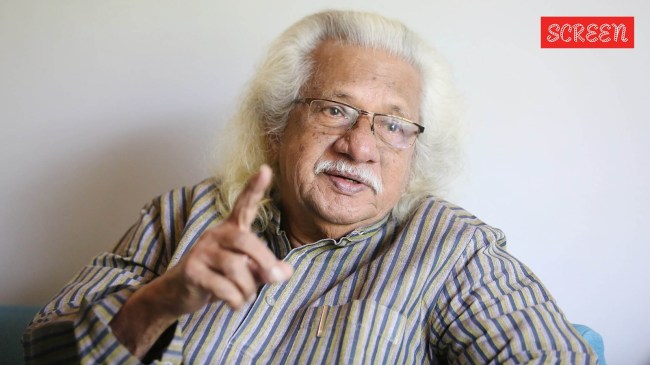

Filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan during an interview in New Delhi. (File Photo/Tashi Tobgyal)

Filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan during an interview in New Delhi. (File Photo/Tashi Tobgyal) What would Adivasi characters have been doing in the average Malayalam film 30 years ago? Perhaps depicted dancing in the jungle. What about women? Perhaps shown being slapped. Dalits? Probably not there at all. How many directors were there from each of these categories? Few to none.

That’s a point to keep in mind while thinking about renowned director Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s controversial remarks about the Kerala government’s programmes to support aspiring SC/ST and women filmmakers. At a film policy conclave on Sunday, he criticised the Kerala State Film Development Corporation’s (KSFDC) scheme allocating Rs 1.5 crore each to two selected projects by SC/ST filmmakers every year, claiming it was excessive and paved the way for corruption; he instead proposed giving Rs 50 lakh each to more filmmakers. He also said these directors should first go through three months of intensive training in budgeting and the basics of filmmaking. Gopalakrishnan was similarly dismissive of a scheme that allocates Rs 1.5 crore to two women filmmakers each year, saying they shouldn’t receive funding just because they are women. The matter escalated quickly, with a Dalit activist filing a police complaint against Gopalakrishnan, who has since doubled down, saying the government shouldn’t waste money on untrained filmmakers.

First, let’s get the facts straight about the schemes. The one for women was launched in 2019-20, and that for SC/ST filmmakers in 2020-21. Of the films funded through the schemes so far, at least three — Nishiddho (2022), B32 Muthal 44 Vare (2023) and Victoria (2024) — have reportedly won awards both at the state level and at international film festivals, suggesting it may not be such a waste of money after all. The “untrained” filmmakers are selected through an elaborate, multi-round process involving industry professionals, including a workshop and an interview by an expert panel, as Kerala Culture Minister Saji Cherian emphasised while rebutting Gopalakrishnan’s claims. National Award-winning director Bijukumar Damodaran, who has been part of the scheme’s selection jury, also issued a detailed counter to Gopalakrishnan’s claims in a social media post, in which he pointed to the mentorship selected candidates receive as part of the scheme.

Second, there’s another side to this story that hints at quite a different picture from that painted by Gopalakrishnan. Indu Lakshmi and Mini I G, two women filmmakers selected under the scheme, have previously made allegations about ill-treatment and verbal harassment by KSFDC officials, including its former chairman, the late Shaji N Karun, who denied the accusations. They’ve talked about how difficult it was to get funds released due to red tape, and how budget-related decisions were out of their control.

Challenging dominant narratives

It is vital to investigate and address such troubling allegations, but the schemes must be improved, not discarded. Their importance is twofold. On the one hand, it is a matter of right and equity to ensure that women and those from marginalised communities have access to these upper-caste, male-dominated fields. It is the state’s responsibility to intervene and actively make sure it happens.

The other aspect is to do with the stories that wouldn’t be told otherwise. The fact that many “cultural” fields remain such upper-caste bastions means that dominant narratives are perpetuated, certain ways of seeing and knowing are universalised, and all other perspectives and histories are buried. That epistemic domination is what leads to an abundance of “tribal dances” but very few tribal protagonists. Improving the representation of the marginalised in the production of knowledge and culture is the only antidote.

Malayalam cinema in particular has barely reckoned with caste. The wave of “feudal” films in the 1990s, representing a regression from a certain modernity and urbanity to out-of-time villages, lords and patriarchs, did not inspire a reaction in the form of anti-caste cinema. What little there is began, more or less, with Kammatipaadam (2016) and has been gradually picking up since then. It’s in this space that the KSFDC scheme for SC/ST filmmakers can make important contributions, and has already begun to do so. For example, Churul (2024), directed by Arun J Mohan and produced under the scheme, uses the murder of a retired police officer to frame a story of brutal casteism.

It is encouraging that the Kerala government and the CPI(M) have taken strong stances defending the schemes and issuing rebuttals to Gopalakrishnan. But it’s equally important to ensure that the functioning of the KSFDC and its schemes is transparent and any allegations are properly investigated.