Opinion Sara Abubakar: A champion of justice, in work and life

Her works expressed solidarity with the persecuted and the downtrodden — be it women or those being persecuted for their ideologies or pushed to the margins by corporate interests. Undoubtedly, her writings and memories will remain an inspiration for generations to come

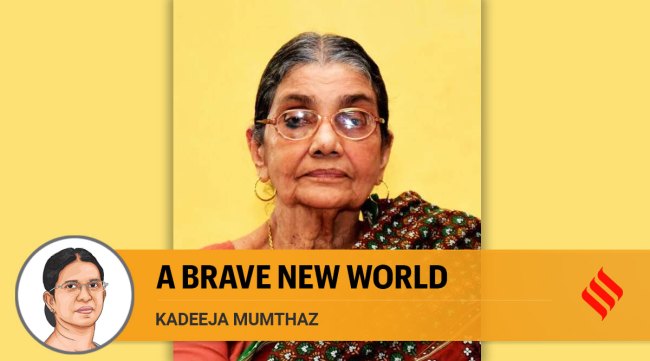

Sara Abubakar passed away last week in Mangalore at 86. (File Photo)

Sara Abubakar passed away last week in Mangalore at 86. (File Photo) Adieu, dearest Sara Abubakar! I wish I were there to bid you the final goodbye. But the next day, as I was speaking to her daughters-in-law, I, for once, felt not going was a good decision after all. It would have been painful to see that angelic face worn down by the wrinkles of time and illness. Her kind and beautiful face is etched in my mind forever.

Who was the writer Sara Abubakar, who passed away last week in Mangalore at 86, to me? Sara and I, like the multitude of contemporary writers born in my community, and the ones yet to tread the same path, are beads on the same string.

Wasn’t Sara a Kannada writer, you may ask? She wrote her novels and stories in Kannada, of course. In that sense, she belongs to the same cohort of literary greats such as Banu Mushtaq, whose works bared the stark realities of life. But why should there be a differentiation based on community and language? The same moral conscience binds us all women writers. A writer’s consciousness comes from shaking off the constraints of our lives and marching forward.

However, for me, Sara is a Malayalam writer. A Kasaragod native, she was born and brought up near the Chandragiri river. She was that gentle presence from an older generation who frequented Kozhikode to attend literary programmes and let others experience the unique Malayalam of northern Kerala.

Her much-acclaimed novel Chandragiriya Theeradalli (in Kannada) is a fine example of Sara’s brave writing. She had studied till Class 11, a feat not small — in fact, rarely possible — for other Muslim girls born in the 1930s in Gadinadu, a socially and educationally backward region on the Kerala-Karnataka border. Although Sara learned Malayalam in primary school, she shifted to Basel Mission School, a Kannada medium school, in fourth grade. Though proficient in both Malayalam and Kannada, she preferred to write in Kannada having shifted to Karnataka after marriage.

Sara became a regular reader of Lankesh Patrike, which also may have led her to take up writing. How could Sara not be attracted to the publication’s sense of independence, social consciousness and honesty? Sara’s essence was no different. She began writing stories and articles. During her childhood, a number of women used to visit her mother to narrate their experiences of domestic life. The embers of one such incident were slowly burning within her and became the subject of her novel Chandragiriya Theeradalli. The novel centres around a woman who is forced to follow an extremely anti-woman custom of marriage, divorce and remarriage in Islam. She ends up challenging religious leaders by killing herself.

But how can a simple, ordinary woman challenge such leaders through her death? That’s where Sara showed her brilliance and courage. The female protagonist, who grew up on the banks of River Chandragiri, did not kill herself by jumping into the river. Instead, she chose the pond in the mosque premises, generally inaccessible to women, for the final act and left the community leaders shell-shocked.

The novel created a furore when it was serialised in Lankesh Patrike. Sara was targeted by Muslim fundamentalists. She was not one to be intimated; it only added more fire to her writing. Editor P Lankesh backed her. The bond with the publication became stronger when Gauri Lankesh took over the reigns of Lankesh Patrike after her father’s demise.

It was while sharing the stage at an event in Kozhikode that Sara expressed her interest to translate Barsa, my Malayalam novel that had a Muslim context, into Kannada. I was shocked for two reasons. One, how was she able to keep a track of the latest works in Malayalam? The second reason was that someone 20 years older than me and a winner of many awards, including the Kannada Sahitya Akademi Award, said she wanted to translate it herself. By then, she had started her own publishing venture and could have easily got the novel translated by someone else. Yet, she chose to do the translation herself because she related to Barsa’s theme. Her words expressed the passion and exhilaration of seeing someone, much junior to her, tread the same path as her. She titled the translation as “Mumbelak” (leading lamp). Sara gave Barsa (the one who doesn’t hide her face, who is brave) a lamp to hold!

Her battles were not confined to the Muslim community. Sara stood shoulder to shoulder with Lankesh and Gauri Lankesh publications that took a strong stand against Hindutva communalism. She translated police officer R B Sreekumar’s work on Gujarat communal violence, Gujarat: Behind the Curtain. She backed the diverse cultural activities organised by Gauri Lankesh. She attended protest meetings in solidarity with the victims of Endosulfan pesticide in Kasaragod.

A sense of justice motivated her writing and actions. Her works expressed solidarity with the persecuted and the downtrodden — be it women or those being persecuted for their ideologies or pushed to the margins by corporate interests. Undoubtedly, her writings and memories will remain an inspiration for generations to come.

Mumthaz is a novelist. Translated from Malayalam by Anita Babu