Tales from Lollywood

Recent movies from Pakistan with edgy characters and relevant stories,hold the promise of a new wave of cinema.

Recent movies from Pakistan with edgy characters and relevant stories,hold the promise of a new wave of cinema.

A group of privileged and fashionable 20-somethings drive around in swanky cars through a city. Drifting between hukka joints and eateries,they spend their days smoking,drinking and partying. This familiar world,however,finds an unusual backdrop in filmmaker Hammad Khans Slackistan,shot in Islamabad.

The 2010 indie film by Khan,a British filmmaker of Pakistani origin,steps away from clichés to bring out unknown facets of the Pakistani capital without denying the countrys turmoil and terror. Mostly in English,Slackistan didnt release in its home country the censor board had suggested cuts that the director refused to comply with but found patronage on the internet and social media. To Khan,the message was clear: Pakistans audience eagerly awaits a new wave of cinema.

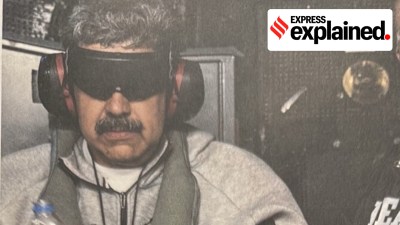

This fact was established more recently when the promo of Bilal Lasharis Waar was released online this year. In contrast to Slackistan,Waar is a slick action thriller with a multi-million dollar budget and mainstream actors. Counter-terrorism is the central plot but Lashari says that it explores this without being preachy or taking sides. It is essentially a revenge saga that will offer people a good cinema experience, explains the 30-year-old.

While Lashari is overwhelmed by the response to the trailer,he does not believe this film will turn around Lollywoods fortunes. Citing Shoaib Mansoors Khuda Kay Liye 2006 and Bol 2010,he adds,Quality films that succeed at the box office are too few and it is unlikely to help an industry that has come too far from its magnificent past.

The 1960s and 70s are considered the most glorious years in Pakistani cinema. After Partition,Pakistan received its fair share of talent but lacked funds and equipment. Singer-actress Noor Jehans directorial debut Chan wey in 1951 was the first big commercial success,which then ushered in the colour film era with Zahir Raihans Sangam 1964,the first full-length feature film.

Pakistans intellectuals often blame Zia-ul-Haq for single-handedly causing a huge setback to the performing arts in the late 70s and 80s. With his overzealous religious ideas,the maulavis gained power and began to exercise moral censorship and the government withdrew all support, says Usmaan Peerzada,founder of the 38-year-old Peer Group,a non-governmental cultural outfit in Pakistan.

As a result,the common man started to shy away from cinema halls,films became an immoral career option,filmmaking became an unviable business opportunity and filmmakers stopped taking any risks. The few movies made were mostly formulaic with a Robin Hood-like hero and a parallel love story. Basically,masala entertainers for the masses, says Shaan Shahid,a prominent Pakistani actor who made his debut two decades ago. Born to the illustrious Pakistani filmmaker Riaz Shahid and actress mother Neelo,Shahid had access to world cinema and understood the drawbacks of his local industry. But I also knew that the industry or the audience was not looking to change yet, says the actor who made his directorial debut with Guns n Roses Aik Junoon in 1999,which made an attempt to fuel the change he craved. However,Shahid admits that he too became a victim of the system and resorted to formula filmmaking.

After the 70s,entertainment had,however,only lost social and public acceptability,the audience still welcomed it into their drawing rooms. The television industry flourished. Socially relevant subjects,tight scripts and strong acting talent gave the medium respectability.

In this scenario of suppression,President Pervez Musharraf is looked upon as a hero. In 2002,Musharraf welcomed private channels into the market and in 2008,lifted the ban on Indian films. He also revived cinema as a subject in mainstream education by financially aiding the courses and purchasing equipment at Lahores National College of Arts. He also helped develop shooting floors at Lahore University. Today,several colleges offer degree courses and parents willingly send their children to international film schools.

But according to Peerzada,Musharrafs biggest contribution was that the requirement for a No Objection Certificate from local authorities for every cultural and entertainment event was nearly nullified. This gave back the artistes their freedom of expression.

Mainstream cinema,however,continues to be plagued by several issues. To begin with,financiers and distributers are still unwilling to take risks. Formula films in Punjabi and Pashto continue to do well and are considered safer bets than mainstream films with contemporary subjects, says Zuraiz Lashari,the president of the All Pakistan Cinema Association.

While Bollywood films have helped fuel the multiplex culture by bringing the audience back to theatres,they have also irked Pakistani filmmakers because a local release is often sidelined as the Indian release is allotted more screens.

The censor board also has double standards as the rules for clearing a Bollywood film and a local production are not the same. Slackistan was banned for the use of the word lesbian and showing youngsters smoking and drinking. But the same rules do not apply to Bollywood films showing here, says Shahid.

Despite these issues,a wind of change is blowing. The emerging talent from the cinema schools is currently being absorbed by TV and music industries after which it spills over into documentary filmmaking and then cinema. The success of Mansoors films has also encouraged the youth tremendously.

Technology to shoot in high definition with inexpensive equipment is further fuelling the indie film scene. The last two years have seen the release of Omar Ali Khans Zibahkhana,which won international awards,Shahbaz Shigris short Sole Search and Afia Nathanials Neither The Veil Nor The Four Walls have been well received in urban centres. This year,Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy became the first Pakistani filmmaker to bag an Oscar nomination for her documentary Saving Face.

You can credit the internet and social media for this change. The country is realising the power of films as a medium and the new,educated generation refuses to be left behind as the world,especially the subcontinent,progresses. So these contemporary films find a platform through Facebook,Twitter and YouTube when they do not find mainstream support, says Peerzada,who feels Pakistani films will carve out an independent identity by addressing social issues.

Shahid,however,says the indie filmmakers need to unite with mainstream players if Pakistani cinema is to be revived. We are a small community of forward-thinking people. If we stand with divided views and approaches,then we can never bring about a change, explains the actor who plays the protagonist in Lasharis Waar. With an active career spanning over two decades,he considers himself privileged to partake of this new wave.

Meanwhile,Pakistan is looking at Bollywood with hope. If Indian distributors bring down the rates from Rs 2 lakh per print then new theatres can come up in the smaller towns of Pakistan, says Zuhair. Both Shahid and Peerzada are hoping that India will screen Pakistani films and then possibly even co-produce a few. The two countries share the culture and language and may find a discerning audience in each other, says Shahid.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05