THE YATRA8217;S WRONG TURN

Ever since it was discovered by a Muslim shepherd in 1850, the Amarnath shrine and the annual pilgrimage to it signified a bond between Hindus and Muslims.

Ever since it was discovered by a Muslim shepherd in 1850, the Amarnath shrine and the annual pilgrimage to it signified a bond between Hindus and Muslims. Having survived the Valley8217;s worst years of violence, a land transfer now threatens to polarise the state. MUZAMIL JALEEL charts the journey of a raging controversy.

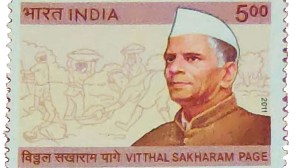

One of the most revered Hindu shrines, Amarnath was discovered by a Muslim shepherd in 1850. Buta Malik and his family became the custodians of the cave shrine along with Hindu priests who came from two religious organisations8212;Dashnami Akhara and Purohit Sabha Mattan. This unique ensemble of faiths turned the pilgrimage spot into a symbol of Kashmir8217;s centuries old communal harmony and composite culture.

In 2000, the J-K Government decided to intervene, ostensibly to help improve the facilities for the annual yatra and the then ruling National Conference enacted a legislation to form a shrine board, with the Governor of the state as its chairman.

As soon as the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board was formed, the Government evicted the Malik family as well as the Hindu organisations that were traditionally involved with the pilgrimage. The board did substantially streamline the pilgrimage but in the process completely destroyed the unique aspect of the yatra when they removed the Muslim custodians of the shrine.

In fact, the idea of a shrine board to provide better facilities to the pilgrims had taken shape following the recommendations of the Nitish Sengupta Committee in 1996, set up by the state Government to identify the causes behind the death of over 200 yatris who were caught in bad weather. The Shri Amarnath Shrine Board Act introduced by the then J-K tourism minister S.S. Salathia set up a board headed by the Governor to 8220;administer, manage and govern the affairs of the cave shrine8221;.

As per the Act, the board has to have 10 members8212;two people who have distinguished themselves in service of Hindu religion and culture, two women with exemplary service to Hindu religion, culture or social work, specially in regard to advancement of women, and three persons with renown in administration, legal affairs or financial matters. The board, however, has 8220;two eminent Hindus of the state8221; as its members while all others can be non-state subjects. Under the Act, if the Governor happened to be a non-Hindu, he can nominate any Hindu of the state to head the board.

The board8217;s finances come from funds consisting of grant-in-aid from the state and Central Governments, contributions from philanthropic organisations or persons, NGOs, registration fee and others who initiate economic activity en route and the 8216;chadawa8217; offerings made by pilgrims.

THE first signs of trouble surfaced soon after Lt Gen S.K. Sinha took over as the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir in 2003, succeeding Girish Chandra Saxena, an apolitical and non-controversial governor. The state had seen a major political upheaval with the defeat of National Conference in the 2002 assembly polls and the new coalition government led by the PDP8217;s Mufti Mohammad Sayeed was at the peak of its enthusiasm. Sinha decided to be a proactive Governor, despite the controversies he created during his stint in Assam, where political parties had similar complaints against him.

In Jammu and Kashmir, Sinha began intervening, first with the counter-insurgency security grid. A retired general, his association with Kashmir had begun in October 1947, when as a young lieutenant he had fought against Pakistan. It seemed Sinha8217;s entire discourse on Kashmir was caught in the trenches of the 1947 war in which he lost his close friend, Major Som Nath Sharma. He enjoyed a lot of clout in the Army, and at times officers would listen to him more than to the elected leadership of the state.

The Mufti government was upset when Sinha started seeking reports from deputy commissioners and superintendents of police. These steps of the Governor led to much bitterness. At one point of time, the acrimony reached such levels that Sayeed boycotted a Unified Command Headquarters meeting called by visiting Union Home Minister Shivraj Patel. The Chief Minister is the chairman of the Unified Command Headquarters, the counter-insurgency grid of the state that includes the Army, paramilitary, police and the intelligence agencies.

The rivalry between Sinha and the ruling PDP took an ugly turn when the Amarnath Shrine Board, of which Sinha was chairman, unilaterally extended the duration of the yatra to two months. Traditionally, the yatra was a 15-days affair, which had been extended to a month. Sayeed rejected the extension, pleading both the additional burden on the security forces and the administration as well as concerns about the weather. Sinha, however, took a confrontational route and soon four Congress ministers from Jammu resigned over the issue. The Congress party had come under severe pressure to part ways with PDP on the matter. The crisis subsided after the intervention of the Congress high command but the animosity grew.

Sinha steadily pushed his own ideas. His Principal Secretary, Arun Kumar, directly wrote to the then Forest Secretary, Sonali Kumar8212;who was also his wife8212;and managed to get around 4,000 kanals of forestland transferred to the Shrine Board. This order was immediately struck down by the Government and a show-cause notice slapped on Sonali Kumar for making the transfer without following procedures, especially the compulsory cabinet approval.

However, when Ghulam Nabi Azad of the Congress took over as chief minister, the relations with Raj Bhavan improved. But Sinha harboured a larger idea of his own 8220;solution to Kashmir problem8221;. He followed his agenda till the day he left Srinagar. Sinha came up with several measures, thinking that promotion of the Hindu past of Kashmir would help increase pro-India sentiment in the Valley. He wanted to create avenues and institutions for a 8220;patriotic8221; version of research into Kashmir8217;s history, politics and conflict in the Kashmir and Jammu universities.

He also came up with the idea of Operation Sadbhavna in which the Army would help renovate Kashmir8217;s Sufi shrines and mosques. Sinha, however, found himself in a controversy as the people started saying the step was aimed at creating a sectarian divide in Kashmir.

A few months ago, Sinha directly wrote to J-K Deputy Chief minister Muzaffar Hussain Beig seeking forest land in Nunwan, Pahalgam and Baltal and the setting up of an independent development authority run by Raj Bhavan. The Government didn8217;t agree to the proposal for an independent development authority but did simultaneously diverted 800 kanals of forestland to the Shrine Board in May.

THE opposition to the Shrine Board acquisition of the land has its roots in a sense of insecurity about any land transfer in Kashmir. People also raised serious questions about timing and purpose of this land transfer. The Shrine Board was constituted as a body to provide and improve services for the pilgrims with the active help of the state Government, police, civilian administration, army, paramilitary forces and also the local Muslim population. This has been happening for past more than a century. Why does the Shrine Board want land to be transferred to them when they already are using this land for decades for the yatra? If the Shrine Board is working to make the yatra smoother for the pilgrims, what scope does it have to conduct massive Sufi festivals everywhere? Why does Raj Bhavan use the Shrine Board to define the cultural and religious ethos of Kashmir in one particular manner? These questions have fuelled the fire of controversy.

Raj Bhavan8217;s desire to wrest control over land has dismayed many, especially since they see the Shrine Board as being an extra constitutional entity, outside legislative oversight. This has happened twice: the legislators asked questions about the functioning of the board and were told they could not ask questions to the constitutional head of the state. This means that whenever the elected legislators had queries about the functioning of the Shrine Board, its chairman took refuge in the constitutional privileges of the office of Governor.

When the new Governor N.N. Vohra took over on June 25, he had his job cut out for him. Kashmir has literally returned to the 1990s with hundreds of thousands of people out on the streets protesting about the land transfer. The situation is fast polarising the state along communal lines and if the crisis is not addressed immediately, it will cause the Government much harm, especially in an election year.

What is the importance of Amarnath?

Legend has it that when Shiva decided to tell Parvati the secret of his immortality Amar Katha, he begun looking for a place where nobody could overhear him. He chose the Amarnath cave, 3,888 m above sea level, in a gorge deep inside the Himalayas in south Kashmir that is accessible through Pahalgam and Baltal in Sonamarg. The cave can be reached only on foot or on ponies through a steep winding path, 46 km from Pahalgam and 16 km from Baltal.

How was the Cave discovered?

According to lore, in 1850 a saint gave a Muslim shepherd, Buta Malik, a bag full of coal while he was with his herd high up in the mountains of South Kashmir. When he reached home, Malik opened the bag to find it full of gold. An ecstatic Malik ran to thank the saint but couldn8217;t find him. Instead he found the cave and the ice lingam. He told the villagers about his discovery and that was the beginning of the pilgrimage.

Every year, lakhs of Hindu pilgrims walk up the mountain to reach the shrine. 8220;Originally the yatra used to be for 15 days or a month,8221; says the Purohit Sabha Mattan president. The sabha organised the yatra before the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board took over in 2000. In 2005, the board decided to extend the pilgrimage to over two months. There is no official record though of when the yatra first began. The annual yatra ends when Mahant Deependira Giri, the custodian of the Holy Mace, carries it to the cave.

How is the lingam formed?

The lingam is formed by a trickle of water falling from a small cleft in the cave8217;s roof. The water freezes as it drips slowly to form a tall, smooth cone of ice8212;the Shivlingam. It gets its full shape in May. Then it begins melting gradually and by August it is reduced to just a few feet in height. On the left side of the Shivlingam are two more ice stalagmites of Lord Ganesh and Parvati.

How did problems over the Yatra start?

n In 2000, the J-K State Legislative assembly passed Shri Amarnath Shrine Board Act, making the Governor the chairman of the board while his Principal Secretary became the Chief Executive Officer of the board. Till then the shrine was administered by Purohit Sabha, Mattan and Dashnami Akhara, Srinagar8212;two Hindu religious bodies.

In September 2003, the PDP led J-K Government took over the Muslim Auqaf Trust run by the National Conference and set up the J-K Muslim Waqf Board with the Chief Minister as its chairman. The government gave mismanagement as the reason but analysts saw a political angle in the issue as well: the PDP wanted to dislodge its arch rivals NC from the administration of the shrines and thus limit its influence.

In 2004, the J-K Government and Raj Bhavan locked horns on the issue of the duration of the Amarnath yatra. The Governor wanted the yatra to be extended to two months from the traditional month-long annual pilgrimage. The then Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed declined, citing an additional burden on security and the state machinery besides weather.

The issue threatened to assume a communal and regional dimension as four Congress ministers from Jammu resigned. Then Congress8217;s entire Jammu leadership along with BJP and other Hindu organisations openly came to Governor8217;s support. The crisis subsided only after the Centre intervened.

In March 2005, the then Forest Secretary Sonali Kumar issued orders for the transfer of 3642 kanals of forest land around the holy cave to the custody of the Shrine Board. The General Administration Department issued a show-cause notice to her, seeking explanation for violation of rules because the order didn8217;t adhere to the Forest Conservation Act and needed prior cabinet approval. Sonali Kumar is the wife of the Principal Secretary to Governor and CEO, Amarnath Shrine Board, Arun Kumar.

In 2005, the Shrine Board decided to bring in commercial helicopter service to ferry pilgrims to Amarnath. J-K Tourism Corporation insisted on using state helicopters but the Shrine Board termed it interference in its work and roped in private companies. The issue was settled in the High Court.

In 2005, Chief Minister Sayeed stayed away from a high-level security review meeting of Unified Headquarters called by visiting Union Home Minister Shivraj Patil, which was a direct fallout of his power struggle with the Governor.

In 2007, a top PDP minister disallowed the Board from constructing a motorable road from Baltal to Amarnath, citing its disastrous environmental implications as the reason.

In 2008, the state Government rejected a report of an advisory committee which had recommended transfer of land in Baltal to the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board for construction of road and raising hutments at various points. Forest Minister and PDP leader Qazi Afzal, however, constituted a committee to look into the issue.

What8217;s the forest land controversy all about?

June 2, 2008: Conceding to Raj Bhavan8217;s demands, the state Government sanctioned the transfer of around 40 hectares of forest land to the Shrine Board. The matter, at the centre of a controversy for the past four years involving Governor Sinha and the ruling People8217;s Democratic Party, is fast turning into a poll issue.

In a statement issued by Raj Bhavan, the state Government has okayed the diversion of forest land measuring 39.88 hectares in the Sindh Forest Division. 8220;The Amarnath Shrine Board is fulfilling all the conditions laid down for the transfer of the land at Baltal, which inter alia includes payment of over Rs 2.31 crore,8221; it said.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05