The politics of laughter

Historians explain the past, and with that our duty is finished. The dead are dead,'' stated A.J.P. Taylor in his essay on the 1945 fami...

Historians explain the past, and with that our duty is finished. “The dead are dead,” stated A.J.P. Taylor in his essay on the 1945 famine in Ireland. “They have become so many figures in a notebook.” Yet their histories need to be told, their values understood and interpreted to unravel the past in all its complexities. This column is more in the nature of constructing, in the words of the Fernand Braudel, a history of brief, rapid, nervous fluctuations in the life of a family tucked away in Masauli village in the Barabanki district of Uttar Pradesh.

It is about a humorist whose writings in English are much imbued with the spirit of the age in which they were written an active, self-confident spirit infused by the rising tide of Indian nationalism. The fact that they are so eminently representative of the period enhance their appeal and ensure to them an enduring quality of historic interest.

Wilayat Ali Bambooq’ (1884-1918), a member of the Kidwai gentry, was educated at the M.A.O. College, Aligarh, the nursery of outstanding young Muslims who were to be heard of a great deal in politics, literature or journalism of the following decades. He experienced the intellectual and political ferment spanning the first two decades of the 20th century, and was a witness to the tremendous upsurge of anti-British feelings among Muslims that paved the way for the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation campaigns (1919-22). He belonged to a movement with serious intents, but while his contemporaries and friends held forth from public platforms, he laughed at British rule and made fun of it in his skits and sketches.

His political pursuits were highly serious but their expression was humorous and satirical. He made roaring fun of that mongrel culture which had evolved in India under British rule. Thus, in his gallery of caricatures, are the England Returned Barrister’ desperately aping the sahibs in manners and speech and pretending to have forgotten his native tongue during his brief sojourn in England. There are, in addition, specimens of the baboo culture in India from the patwari to the deputy collector and the honorary magistrate, comic both in their servility to their white superiors and their arrogance towards the common people.

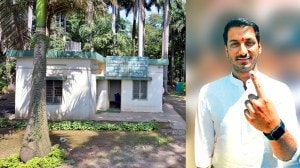

Bambooq’s home in Barabanki was the centre of a lively group of radical intellectuals and simple lovers of good food and intelligent conversation. On many weekends his friends would travel to this dusty town armed with resolutions or memoranda for forthcoming Congress or Muslim League meetings, and spend the evening pulling leisurely at a long hubble-bubble, filling the air with the smoke of scented tobacco, bandying Urdu or Persian ghazals, reciting their compositions in verse or prose, or shouting at each other in violent, political argument. Sons of the feudal families whose earlier generation had never earned their own living, they were no lean and hungry carcasses with dire intents against the colonial government. The nationalist agitation was still the affair of the educated middle class; freedom’s battle was still fought with words.

It was the kind of political setting in which the writer and the speech maker rapidly came to the forefront. Bambooq, for one, made his mark quickly as a writer. And yet Bambooq had only one foot in Lucknow’s political and literary elite; the other foot was firmly planted in the family past. He tried preserving the values he had inherited from his family past hospitality, filial devotion and constancy in friendship. His house was packed with guests and poor relations. It was a free hostel for any boy from the village who had to study in the local high school. It was a gratuitous inn for country bumpkins whom business with the magistracy brought to the district town. It was the den of local nationalist agitators, the rendezvous of politicians and journalists.

In this house, rustic coarseness and urban refinement lived cheek by jowl and country yokels and sophisticated gentleman sat down to eat at the same table. Bambooq accepted every tie of kinship or friendship he had inherited. He was not the least embarrassed if his rustic past intruded on his urbane present. As he sat among friends, a country bumpkin with his dhoti tucked up to his knees and bedding swung on his long staff would barge in.

Invariably, he would announce to the company that he was his uncle or cousin by some twist or turn of the Kidwai blood stream. His generosity was clandestine and only limited by his income and the debts he could raise. When he would drag one of his ragged and shabby looking visitors into a corner to whisper to him, the household would suspect that some money was being passed on. His acts of generosity came to light after his premature death at the age of 33 in July 1918.

Bambooq’s values and way of life would have perished with him but for the fact that Rafi Ahmad Kidwai, his nephew, was growing up in the same house. His uncle’s example sank deep into the recesses of his being. From his uncle, he learnt to take no heed for the morrow, to cast his bread on the waters, to conceal the bounty of his heart like a private vice, to defy time and circumstance to stale his friendships or wither his loves and loyalties.

Joking and laughing, he made events and things look easy. When Rafi moved to ministerial mansions in free India, he recreated in them the setting and atmosphere of the home in which he had grown up as a boy. At New Delhi’s 6, Edward Road (now Maulana Azad Road), the past and the present lived cheek by jowl.

Rafi largely relived Bambooq’s political style. Like his uncle, he transacted business amidst roaring fun, and banter and gossip. He did not run around the world looking for a Hero because he had found one in Jawaharlal Nehru. He took after his uncle’s terror of the public platform and his preference for the backrooms of politics. “When he talked,” recalled the civil servant Y.D. Gundevia, “he blinked and blinked and blinked, and sometimes looked at you with his eyes almost shut.” As it turned out, his commitment and his staying power were greater than that of almost anybody else who was thundering from the platform of the district.As an essayist Bambooq could hardly be expected to create a large following.

What he could do was to stimulate the imagination of his readers, and this he did not only in special cases where minds similarly attuned used his articles creatively but also in the widest circle of his readers. Credited with literary excellence, his sketches’ claim to survival rests on being part of the social history of the time.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05