‘That’s the sense of fulfilment… when you go back at night, to feel that you have done everything you can’

• I’m in Chennai, this week, in what you might describe as the corridors of compassion. With me today is Dr. V. Shanta, chairperso...

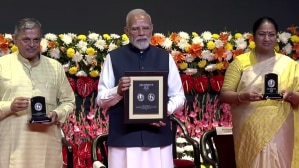

• I’m in Chennai, this week, in what you might describe as the corridors of compassion. With me today is Dr. V. Shanta, chairperson of the Adyar Cancer Institute. Congratulations, first of all, for your Magsaysay Award: one of the very few, I believe, to go to a doctor.

(smiles) That’s what I’m told and I certainly feel very privileged and honoured — I was overwhelmed when we got the news. But the most important thing is that the whole Institute feels proud. We all believe that it is the Institute that has got the award. The Institute is one, we are all part of it, and I am so proud everyone feels here they are part of the family of the Cancer Institute.

• But, Dr. Shanta, while I’m sure they are very proud of you, as we are as well, it’s not easy to run an institution like this in India, particularly one that caters mainly to the poor and runs on very little more than donations.

It certainly has been a very long and arduous task, right from January 18, 1954, when we started with a hospital of twelve beds and just two doctors, and our patients were all housed in Seva Gram-type huts.

• And in those days cancer treatment was quite a rarity.

There was no perception about cancer at all. People said cancer is something that people die of. When our founder, Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy, was campaigning for a cancer hospital, the Tamil Nadu Health Minister of the time told her: Why a cancer hospital? Only old people get cancer, and they die of it in any case. Why do you want to want to waste money on them? That was how people thought then. Dr. Reddy had lost her sister to cancer at a very young age, in 1923. She herself was the first woman medical graduate in the country. We were under British rule then, and there were no facilities for cancer treatment. She determined that she would build a cancer hospital; that was her dream.

• Since the 1950s, you have not only maintained this tradition of free treatment for the poor, you’ve also kept your technology at the cutting edge. I believe this is among the very best equipped cancer treatment centres in the country.

I think it was our founder’s wish to make us an institution of service for all. We have always tried to maintain the best treatment procedures available, to provide state of the art treatment to everyone, irrespective of class or community. It’s been hard because the cost of medical care has gone up. When we started in 1955, the only procedures were surgery or radiation—and without the present day sophistication. So it didn’t cost much. Food for our patients used to be sent here from Dr. Reddy’s house.

• I can see the foundation stone here, laid in 1952 by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. You were there.

I was very much there. We still have some photographs with Nehru.

• But this is amazing — I mean, in those days, who in India knew about cancer care? Cancer was seen as a near-certain death sentence until just 10 or 15 years ago.

Well, the perception isn’t very good, even now. But back then there were people like Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy who felt strongly that cancer was treatable. She had seen a lot of people being cured of cancer when she trained in Boston. So she said: It’s no use saying cancer is incurable; it’s up to us to see that something is done for it.

• Today many cancers are curable, but it’s very tough if you get cancer and you happen to be poor. Cancer treatments are very expensive — it’s wrong.

It is very wrong. But there is something I’d like like to say, as a message to people. Treating early cancer is not a prolonged procedure, it is not expensive. The majority of our people tend to come at a late stage and that’s why the cancer becomes difficult to handle. Therefore, our major focus is to establish a network of early detection centres.

• Particularly among the poor, providing them regular, extensive and detailed medical check-ups.

Our first problem is the lack of awareness, the lack of education. People have to be educated about cancer — that it is curable and, not only that, it is preventable. There are so many methods of treatment — over the years medical advances have made so many strides. Now we are even able to diagnose a cancer in what is called the pre-cancerous condition.

• But at a centre like this, which mainly caters to the very poor, are you able to detect a lot of early cancers, or pre-cancerous cases?

Of course not. That is our greatest failure. And that is why I said we should establish an early detection network. Nearly 75 per cent of the patients who come here are in the advanced stage.

• And I would say that more than 90 per cent of those who come here are very poor.

Not 90 — maybe about 65 to 70 per cent of our patients are poor. We have 428 beds, out of which 60 per cent are general beds and 40 per cent pay us. It is hard — each patient costs a lot of money. They come from such long distances. We even have patients from the North-Eastern states — anybody from Assam or Nagaland who can come here for treatment does so. And, of course, there are people from Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Pondicherry and Tamil Nadu.

• And you provide them the same treatment as you would your paying patients?

There is no difference in treatment. Whatever an A-class or a Super A-Class patient can get is provided to all, irrespective. That has been our greatest advantage, our greatest achievement, and at the same time our greatest burden.

• Many would be surprised to know that, even at this stage, you still conduct surgeries. I know people cue up saying: Get Dr. Shanta to do my surgery. Do you choose between patients, or do you go by the seriousness of the case?

At the moment I see only a restricted number of patients — after all, age also has its limitations.

• We are in one of your general wards now, and I can see almost every bed has been funded by donors. When your poor patients come to you, do you find they have an understanding of what they are up against?

The majority — no. But 50 per cent of them come because they have been referred here by doctors who have told them they have cancer. Gradually though, over these 50 years, I have seen that people’s awareness has grown. And, as we always say, our patients have been our best ambassadors. If you go to Nellore or some area like that, you will see patients telling others they can come to such this place and it will be alright; they don’t have to worry about cancer. That’s one of the achievements of treatment today — if patients come in early, we can send them back to normal living.

• This is a unique experiment. The Magsaysay Foundation may have recognised it now, but I think the people who have known the Institute have talked about it for a long time.

Well, by the grace of God they do know because it is the poor who carry the message. We always find that it is not the rich who carry the message — they always find something to criticise. But the poor are very, very happy.

• You’ve done battle againt cancer for fifty years, and I see such joy in your face when you talk about advancement in treatment. Do you now see cancer being conquered in your lifetime?

No, I don’t believe that cancer will be conquered in my lifetime. But so much has been achieved. From a time when there was no cure at all — no child with leukemia survived beyond 10 to 12 months in 1955. Look at the paediatric ward today — 50 per cent of them go back to normal lives. They grow up, they get married, they have children, they come back to visit us. I tell them that’s my greatest joy, to see them coming back. That’s the sense of fulfilment: when you go back at night, to feel that you have done everything you can.

• Did you ever imagine in the fifties that you would come to this stage? That a child leukemia patient would come back as an adult with a normal life?

No, not in the 1950s. But science grew very rapidly in the period between 1965 to ’75 or ’80. That was a period of extensive medical information.

• Talking to your peers, other people who specialise in cancer, I am told that you’ve also contributed a lot to research. It’s also mentioned in your Magsaysay citation, you’ve been contributing articles to journals….

You cannot make any progress in clinical work unless you study your own patients. Your patients are your best material — you can call it research or whatever you like, but research is not just what happens in the laboratory. You have to study your patients, the long term effects of treatment, results, and you have to see how to change your methods to improve those results. Even now, our major work is to enhance results in the advanced stage of the disease. There’s no point in my sitting back and saying: They are advanced, I can’t do anything. That has also been our major contribution in cancer care.

• But how come, while we have so much of the disease in India, Indian cancer research has not really kept pace. As you say, there are so many patients, but no real breakthroughs have come out of India.

This is, unfortunately, a question we repeatedly have to answer, about Indian research not being up to the mark. There are two types of research. One is clinical research, which as clinicians we can see and study. A lot of work has been done on the epidemiology of cancer, how it comes about, how it spreads and what you can do in terms of treatment. But what we don’t have is laboratory research, which costs a lot of money. Today, we have a very good oncology department, but the cost per investigation is very high. We have the country’s first hereditary cancer clinic, which means we are able to detect certain types of cancer, especially of the breast, which have a genetic basis. We can locate whether or not an individual has the gene. Per test, this costs about Rs 50,000 — which is probably what most corporate hospitals charge.

• What are the big disappointments, so far, in the way cancer treatment has progressed?

I think we have not done enough in the area of cancer education. We have not done enough to get patients to come in early.

• I am surprised to see how many young women there are here.

Our cancer patients are about 10 years younger than in most affluent countries—probably because they have gone through more problems. So we have cancers, especially cervical and breast cancers, in a much younger age-group. Most Western women with cancer are post-menopausal, whereas we have a much larger number of pre-menopausal patients. It is a biological difference we are trying to investigate, and that is where gene expression studies are very important. But they are very expensive—my molecular oncology division wants at least a crore of rupees per year.

• What are some of the firsts that the Institute can count? Quality of care….

Certainly quality of care, but we have many firsts to our credit. The most important is the Cobalt-16 radiotherapy machine installed here, the first in the country and in the whole of Asia. It was a gift to us from Canada—it was almost a Christmas gift, December 25, 1957. We always call it our tryst with destiny because it made us famous overnight. It was almost as big as the (Magsaysay) Award. It made a lot of awakening happen—everyone wanted to know about this hospital in huts that had a cobalt unit.

• How does the care here compare now to other centres in India?

I think, as far as cancer care goes, I am very proud to say that we are one of the best. I don’t want to compare with others, but I think that we provide the best in terms of quality and personalised care.

• The big problem right now is that while available facilities are increasing, so are the costs. So how do you take medical care to the poor? It’s very cruel to tell a family that all this is available, but your child, your spouse, your sibling cannot get it, because you can’t afford the cost.

This is what I have been saying all the time about changing medi-care. The corporate ethos is becoming a major problem. We have tried to do the best we can.

• This is the city where Apollo came from.

I know. But things have changed all over the country. I think Apollo came much later. The corporate ethos had already started in Bombay.

• You keep saying that we should build centres like Mayo, where the rich pay for the poor. Can it happen?

I don’t know. We tried it, but we were not successful. When I visited Mayo, I decided we would start something like this. We asked an IAS officer — I don’t want to name him, he came with his mother who had breast cancer. All we wanted was one month’s salary, and he said: My mother’s salary is Rs 100.

• So she should get free treatment? And this was an IAS officer?

Yes. This was in 1957 or ’58.

• So, anybody who can get away with free treatment in India, wants it?

We have a very good way of evaluating our people. But it is not very easy. Many times, we are taken for a ride.

• But your dream would still be the Mayo clinic?

Very much so. I think it is so ennobling when you go there — people are so happy because you don’t talk in terms of money when it comes to health and disease. When a person is ill, they don’t want to talk about what money they have to pay

• That is the saddest part. There are economists who will tell you that it is one thing to say that there are only such-and-such number of Indians below the poverty line. But of those who are marginally above the poverty line, 99 per cent will go below it should there be one illness in the family. Cancer would drive a very large number of lower middle class families below the poverty line, in fact.

Absolutely. It’s not only the lower socio-economic groups. Even middle-class people, a teacher, or somebody who earns about Rs 8000 — how can they afford treatment?

• And now we’re in the paediatric ward?

That’s right. Most of the children here have leukemia, blood cancer. Leukemias and lymphomas constitutes 50 per cent of all cancers in children. My work with leukemia started under international collaboration with the NCI (the National Cancer Institute in the US). In those days, there was no blood cancer treatment specialisation. We found we were able to give the same treatment in India as was being given in the United Kingdom or the United States. But our results were not as good. Many of our patients came back. So we talked to many people and we started the collaboration with the NCI, and now with the INCTR—that is the International Network for Cancer Treatment and Research in Brussels. We have found that, biologically, the types of leukemias here are very different from those that occur in the affluent countries.

• Dr. Shanta, tell me—you’ve been doing this for 55 years. It must have been tough going at many times. Tell me some incident, some story that’s kept you going.

There are any number every day. We had a girl here once who was doing her Ph.d. at IIT. I forget her name, but she had leukemia. We treated her and she’s perfectly alright now. She was very bright — she applied to the Commonwealth Foundation and she was selected. Unfortunately, when it came to her medical examination, they tried to reject her because she had had leukemia. I took up the challenge with the Commonwealth Foundation; I wrote to one of our major leukemia experts in the UK; I told them her chances of recurrence were extremely low — why on earth were they doing this? She got through — she got her Commonwealth Fellowship, and now she’s doing research in the US, she’s married, she has children.

• You also had competition within the family, didn’t you? Two of your maternal uncles were Nobel laureates: Dr. C.V. Raman and Dr. Chandrashekhar. That must have put pressure on you.

Well, we certainly looked at them with awe and reverence; they were an inspiration.

• And nobody said, in this family of mathematicians and physicists, what is this young woman doing taking up medicine?

Yes, nobody in the family had gone into medicine. But I felt I would never come up to their level, so I thought I’d take it up.

• Dr. Shanta, what you’ve done for the last 55 years has been very remarkable.

It’s the team — the team has been very good. I’ve been fortunate and very privileged that this opportunity has come to me. As for the award, it’s just the name that has come to me — I keep telling everybody that I’ve taken the name for all the work they have done.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05