Storms in a world cup

Whenever I wish to get an update on our One World order 8212; how much it is coming together, how much it is falling apart 8212; I try to ...

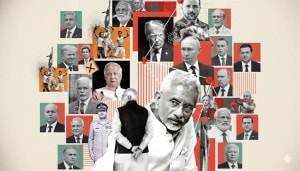

Whenever I wish to get an update on our One World order 8212; how much it is coming together, how much it is falling apart 8212; I try to take myself to an Olympic Games,8221; Pico Iyer once said. When we finish canning the confetti and locking away the firecrackers we had been hoarding for Sunday8217;s final, we may find that the World Cup just concluded too offers an update on our multi-world disorder. Flag and logo fluttered in a fierce breeze of nationalism and corporate control, whispering warnings about the emerging international and financial powers being balanced beyond many a boundary. It is a balance being calibrated with boycotts, or at least the threat of them.

World Cup 2003 leaves more omens than memories. The portents were abundant. The logo police were on permanent patrol, their sensors alert to that contraband can of cola not produced by the official sponsor, or that T-shirt promoting a mobile phone competing with the official product. Elsewhere, confusion prevailed well into the tournament on whether rival captains would show up for the scheduled toss.

Don8217;t blame any of it on the cricketers. It8217;s the game itself that appears to be in great danger, the commonwealth of cricket could be heading for a split. The eighth World Cup may have been fashioned as a celebration of racial unity, but the cracks are deepening along potent faultlines: rich versus poor, black/brown versus white. Scan cricket8217;s few remaining journals, and you find more foreign policy and security interventions than lyrical descriptions of reverse sweeps and leg-cutters. In the latest issue of Wisden Cricket Monthly, the ratings are back. But with focus on South Africa 2003, it is cricket8217;s crises that are being ranked not the performances of the men in coloured pyjamas.

At the epicentre lies England8217;s boycott of their league match in Robert Mugabe8217;s Zimbabwe. More than the final decision to stay away from Harare, it was the preceding now-we-play-now-we-don8217;t routine by Nasser Hussain8217;s squad that was more telling. First, the folks at Whitehall murmured doubts about the ethicality of gracing an event in a country run by a man with little respect for land or human rights, but clarified that the Blair regime would leave it the cricketers to determine whether to forfeit their four points and compensate the organisers. England, to hasten over the soap opera in London, in the end sought relocation of their match on grounds of safety and security 8212; the only grounds, it so happens, on which the ICC is entitled to shift a match venue.

Australia8217;s politicians too had made demurring noises about transacting cricketing business in a country suspended from the Commonwealth, but in the end Ricky Ponting 038; Co turned up for their fixture. As did India and Pakistan, the other major teams in the Group of Death, clucking in solidarity. The Indians dismissed any suggestion of a security threat, while former Pakistan captain Imran Khan reasoned that if England could moot a boycott on moral grounds, Islamabad too had better consider calling off a tour of England, given its membership of 8220;the coalition of the willing8221; then readying to invade Iraq. And to complete this show of Afro-Asian unity, South Africa threatened that they too could join Zimbabwe in calling off a forthcoming tour of England.

It did not begin here, and it shall not end here. New Zealand shipped out of Pakistan mid-tour last summer; Pakistan went on to play a home series against Australia in Sri Lanka and Sharjah! On the eve of their Caribbean tour, Australia have already begun making inquiries about shifting their matches from strife-torn Guyana.

8217;Tis truly the season for boycott bargains. India appear to be waking up to the leverage their audiences and markets provide. Pakistan, their cricket board depleted of funds and desperate for the crowds and endorsements clashes with their subcontinental rivals garner, are appealing to India to rescind their pledge to suspend bilateral tours till cross-border terrorism registers a dip. The ICC had to meekly see through a lively World Cup with the patronage of Indian spectators 8212; on television and at South African venues 8212; before it could contemplate reissuing its earlier ultimatum: that it could ban India if the contracts issue, tactically kept in cold storage for the past six weeks, is not settled to the council8217;s satisfaction.

There was never a golden age of cricket untainted by political and financial spats. In the years preceding independence, writers marvelled at C.K. Nayudu8217;s exploits against the English, likening each six to a nail in coffin of Empire. West Indies made a case for self-government 8212; to themselves and to their colonial masters 8212; by establishing moral equivalence on the field. The Australians, in the 19th century, trounced visiting English teams to prove that the descendants of convicts were equal to the best the mother country could produce.

Those engagements took place on the field, the flow and ebb of the game paralleled wider historical and social narratives. Now, wider political and financial expediencies appear to dictate whether teams will even take the field.

The boycotts threatened range from the ludicrous to the judicious. As the war on terror rages in ever more instalments, personal safety is a query each person assesses anew each day, professional and tourist alike. But safety concerns can so easily fall captive to cultural stereotypes. In an era of orange alerts on the lonely superpower8217;s shores, leaving it to England8217;s men in blue to make individual declarations on the centres of cricket they would dare venture into post-9/11 must be deemed ludicrous. On the other hand, premising tour cancellations on specific terrorist strikes or intelligence information 8212; as the Kiwis did 8212; is understandable.

Cricket has always made the commonwealth a safe place for hypocrisy, the noble game has always made it easy to mask petulance and greed with the moral position. Trouble is, finding neutral umpires to make judgement calls on these may be nigh impossible.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05