Purple anklets of pain

Malka Pukhraj died at 92 in Lahore on Wednesday and is buried in her family graveyard, the Shah Jamal. One can readily imagine the earth mur...

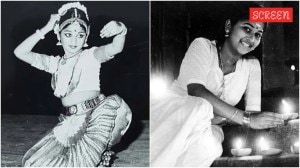

Malka Pukhraj died at 92 in Lahore on Wednesday and is buried in her family graveyard, the Shah Jamal. One can readily imagine the earth murmuring azad nazm (free verse) from her beloved Faiz: Tum mere paas raho/mere qatil mere dildar/jis ghadi raat chale…beyn karti hui hasti hui gaati nikle/dard ke kaasni paazeb bajaati nikle. ‘Stay by me, beloved assassin/when the Night sets out intoxicated, laughing, singing, tinkling her purple anklets of pain’. Pukhraj loved free verse, she seemed to have a modern, open, elegant mind which absorbed the semi-classical masterpieces of Ghalib, Dagh (Zahid na ki buri), Meer and Allama Iqbal (Tere ishq ki itna chahta hoon). She also researched and showcased hidden treasures like her native Dogri and Pahari songs (Palpal bei jaana, bei jaana, o jinde: ‘Stop a moment, dear one’), the eternally haunting ‘Lehra ke jhoom jhoom ke’ or the exquisite nazm, ‘Lo phir basant aayi’. And especially, she sang Hafiz Jullundry’s lyrics that became her signature tune, Abhi toh main jawaan hoon. This essential gentleness expressed itself in her later love of quiet solitary pursuits like gardening and embroidery.

Born into a peasant family in Jammu, she was the child of a bitterly unhappy marriage and wrote with brutal honesty in her life story, published last year, that she grew up willful and moody, unable to demonstrate her affection to anyone, even her own husband and children. She began her talim at age three with Ustad Ali Baksh Qasuria, father of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, learned dance from other ustads in Delhi and at age nine became a civil servant, earning Rs 500 a month as a gazetted officer in Maharaja Hari Singh’s government, growing into a favourite despite court intrigues. She escaped by a whisker from the furious Maharaja of Patiala because she refused to kiss his foot and amidst the growing communal discord, left for Lahore at eighteen, where she eventually married a government employee Syed Shabbir Hussain Shah, who was also a literary figure and introduced her to educated society. Concerts, children, shikar parties, failed businesses, greedy relatives and a cheating son were later highs and lows. Not only did she sing bhajans at the Jammu temples in Hari Singh’s time, she embroidered a portrait of Babaji (Guru Nanak) that a Sikh admirer installed in a Toronto gurdwara.

Though Pukhraj stayed on in Pakistan, she yearned for India where she had a devoted following. When I met her daughter Tahira Syed in New Delhi for an Express interview, I found her eloquent and dignified. It was hard to relate her to the grainy, black-and-white memory I had of her mother singing on Doordarshan, eyes hidden by enormous diamante-rimmed shades. But when she sang in Connaught Place in the heart of Delhi the connection was evident in the misting eyes all around.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05