POINT OF NO RETURN

This village in Punjab was once called Patton Nagar because in the Indo-Pak war of 1971, a large number Patton tanks were captured here.

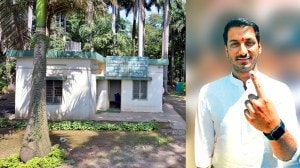

This village in Punjab was once called Patton Nagar because in the Indo-Pak war of 1971, a large number Patton tanks were captured here. Now called Bhikhwind, the village in Amritsar district is just 8 km from the Indo-Pak border. Amid the typical village houses here, there is a dilapidated, mud house that has, oddly, a marble nameplate at the front. Over the past few months, a large number of journalists and politicians have been making their way here, who stop and read the nameplate: Sarabjit Singh Atwal s/o Sulakhan Singh Atwal.

For his neighbours, friends and acquaintances the words gouged out on a marble slab are the only credentials of a man who has been sentenced to death in Pakistan after being accused of being a spy involved in bomb blasts that took 14 lives.

Each villager has his own version of how Sarabjit went to Pakistan but they all agree on one thing: Sarabjit, who worked as a daily wager was ‘‘nondescript, poor and not the type who would do such a horrific thing.’’

Jaswant Singh, one of the Sarabjit’s close friends, goes back to August 28, 1990. ‘‘We were both working as labourers on a construction site which was pretty close to the border. During those days, there no wire fencing separated the two sides. The border was demarcated by a few equidistant stones.’’ He admits that after their dinner, both of them got drunk and since it was ‘‘very humid’’ inside, they went out to sleep in the open. ‘‘Sometime during the night, I remember Sarabjit saying that he was going to ease himself. When he did not return, a couple of friends and I went looking for him and when we did not find him, we feared he might have strayed into Pakistan.’’

A few days later, their fears were confirmed. But they were to receive a further jolt when they were told that he had been arrested in Pakistan on charges of spying and engineering bomb blasts.

Even if Jaswant Singh’s version is dismissed, there are many who believe there are a lot of loopholes in the manner in which charges have been framed against Sarabjit. Gurcharan Singh, general secretary of the District Congress who claims to know Sarabjit’s family since he was a child, says, ‘‘The authorities claimed they had arrested someone called Manjit Singh who was wanted for perpetrating some disruptive activities in Pakistan. His confession was taken in police custody. Such a confession is not admissible in India. The police can forcibly put words in someone’s mouth.’’ Then, with some bitterness, he continues, ‘‘Look at the stark contrast. On one hand, Pakistan wants to execute Sarabjit on the basis of a dubious confession. On the other hand, the Indian Government is giving the opportunity of a proper trial even to those who were directly involved in the attack on Parliament House. We plead for mercy from Pakistan’s Government.’’

Whether his straying into Pakistan was accidental or not, the hiring of youngsters by intelligence agencies for espionage is not uncommon in the border districts of Punjab. In the absence of employment opportunities in Gurdaspur, Ferozepur and Amritsar, many young men agree to help the intelligence services.

‘‘It is not a matter of one Sarabjit. Most people have this misconception that Punjab is a rich state. Look around this area and you won’t find any decent industry, school, college or vocational training institute. What avenues does a youth have?’’ asks farmer and former sarpanch Tejpreet Sandhu, who goes by the name of Peter. He was the first to send a resolution to both the governments of Pakistan and Indian, saying that Sarabjit had been arrested under a mistaken identity.

Born into a wealthy family, Peter went to study at a famous public school and then went to London for higher studies before returning to join his family vocation of farming. Passionately concerned about his region, Peter, who is nearly the same age as Sarabjit, admits he was luckier. ‘‘Unless you are born with some advantage, it is difficult to sustain yourself in this part of the state. Sarabjit was a landless labourer who struggled to make ends meet. Many youths like him are toiling ceaselessly on harvesting other people’s crops or constructing someone else’s house for a pittance. They can be tempted by a lucrative option by any intelligence agency.’’

But the money that these agencies pay doesn’t last forever. As Kashmir Singh, who recently returned from Pakistan after 35 years of captivity, says, ‘‘In my absence, no pension, no stipend was ever given to my family.’’

In Sarabjeet’s case, influential residents have done their bit. A request to former Chief Minister Amarinder Singh facilitated a class IV job at the University in Amritsar for his wife. Other than his wife, Sarabjit’s family comprises two daughters and a sister who has been the most visible in the media. There are murmurs that the limited financial assistance has soured the relations between Sarabjit’s wife and his sister. The latter and the elder daughter are in Delhi these days, taking up Sarabjit’s case with higher authorities. The younger daughter, 16-year-old Poonam, seems to be oblivious of any such rift. She was not even a month old when ‘‘papa went missing.’’ Today she is preparing for her Class X exams. Concerned about her mother, who she says has got a fresh lease of life ‘‘after the death sentence was postponed’’, Poonam is mindful of the relentless media attention. ‘‘I know they are concerned but I am preparing for my exams and sometimes the media can be distracting. Someone or the other comes to our house every day and, like yesterday, they often leave way past midnight.’’

The intrusion apart, the media appears to have left an impression on her. So Poonam wants to ‘‘pursue humanities and then become a journalist, preferably the ones who are on television. This will make people remember my work as well as my face.’’

Eight kilometres from Sarabjit’s house is another village, a village that now has instant recall. Locals direct us here to the place from where Sarabjit ‘‘accidentally strayed’’. Farmers point to the enormous fence that has been erected in the middle of their fields. ‘‘This pretty much shows the apathy of Government. Without their consent, a portion of the fields has been taken away from the farmers. Till about a few years ago, there would be a monthly compensation of Rs 2,500 per acre, but even that has stopped. The farmers aren’t even allowed to install tube wells,’’ says Sandhu.

A farmer, whose land has been ‘‘separated’’, explains how his movement is restricted. ‘‘Please don’t take my name. The authorities might not like it, but I tell you that if I have to visit my field on the other side I have to depend on the goodwill of the Pak Rangers and BSF. The entry is barred during the times when relations are tense and even normally there are a lot of restrictions.’’

If he has to tend to his field, he has to be accompanied by BSF soldiers. He can cross the border between 9 am to 5 pm. But the fields and the houses on both sides of the border look alike.

A short story by Sadaat Hasan Manto is very popular in these parts. Titled Toba Tek Singh, it is the tale of a simpleton who loses his life as he is unable to differentiate between the two countries. For the people of his village, Sarabjit Singh’s life is at stake because of a similar but inadvertent error.

— With inputs from Dharmendra Rataul

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05