The Udaipur Mewar family feud: Of kings, palaces and ‘royal’ trouble

Earlier this week, the decades-long property feud among the former Mewar royals played out in full public view following the ‘coronation’ of BJP MLA Vishvaraj Singh Mewar. The Indian Express travels to Udaipur as battles and palace intrigues of a bygone era come alive in a fight for royal legacy.

A view of the Udaipur Palace (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

A view of the Udaipur Palace (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)Samor Bagh, with its old-money grandeur, is a space fit for a king — rich wall-to-floor carpets, framed black-and-white photographs of family members, intricate wooden wall pieces and delicate chinaware lining a wooden shelf. But Vishvaraj Singh Mewar, the occupant of this sprawling 60-bigha estate in Udaipur, believes he rightfully belongs elsewhere: to the 16th Century City Palace, the five-acre headquarters of the erstwhile Mewar royal family.

It’s a desire that has placed the 55-year-old at the centre of a public tussle in his extended family as, on November 25, hours after he was ‘anointed’ the head of the Mewar royal family, Vishvaraj and his followers were involved in a public skirmish with the family of his estranged uncle Arvind Singh Mewar, 79, and cousin Lakshyaraj Mewar, 39.

The skirmish, which led to stone pelting and clashes, came after Vishvaraj and his entourage were prevented from entering the disputed Udaipur City Palace, which is currently under the control of Arvind Singh’s family, to make a customary visit to Dhuni, a piece of land within the palace compound that’s considered sacred by the family.

Vishvaraj Singh Mewar and his wife Mahima Kumari at Samor Bagh, Udaipur (Express photo by Parul Kulshrestha)

Vishvaraj Singh Mewar and his wife Mahima Kumari at Samor Bagh, Udaipur (Express photo by Parul Kulshrestha)

The events served to not only highlight the relatively unknown battle for the Mewar family property, estimated to run into several crores, but also brought into focus the lives of Rajasthan’s erstwhile royals, and the sway they hold over the public.

“It was my right to visit Dhuni after my father’s death,” Vishvaraj, who is also a BJP MLA from Nathdwara, tells The Indian Express as he sits on a plush black sofa in his office with his wife Mahima Kumari, 52, the BJP MP from Rajsamand.

Politics, he says, is an extension of his public persona. Vishvaraj, whose father Mahendra Singh was a former BJP leader who later moved to the Congress, contested his first Assembly election last year, months after joining the BJP, and was fielded in Nathdwara against Congress veteran C P Joshi, a five-time MLA. Although Nathdwara was considered a Congress stronghold — Joshi had won his previous election by 16,000 votes — Vishvaraj Singh defeated him by 7,504 votes.

The gates of the City Palace where Vishvarah and his supporters were stopped by his cousin Lakhsyaraj. (Express photo by Parul Kulshrestha)

The gates of the City Palace where Vishvarah and his supporters were stopped by his cousin Lakhsyaraj. (Express photo by Parul Kulshrestha)

Earlier this year, Vishvaraj’s wife Mahima, who helped him with his campaign, beat Congress’s Damodar Gurjar in the general election by 3,92,223 votes. Since his “coronation ceremony” at Chittorgarh — once the capital of the erstwhile Mewar kingdom and home to the Chittorgarh Fort — earlier this week, the BJP MLA has been referred to as ‘Hujoor’, a royal honorific given to the ‘king’. Arvind Singh and Lakshyaraj continue to be referred to as ‘Hukum’, a broader term of respect for male members of the Rajasthan ‘royal’ family.

At palace gates, a public feud

One of the oldest royal families in Rajasthan, the Mewar family traces its lineage to Udai Singh-II and his son Maharana Pratap or Pratap Singh I, among Rajasthan’s most revered warrior kings. The erstwhile kingdom of Mewar comprises the present-day areas of Udaipur, Chittorgarh, Banswara, Rajsamand and Pratapgarh.

The current feud in the Mewar family is between two sets of descendants of Bhagwat Singh. The 75th Maharana of Mewar, Bhagwat Singh was the adopted son of Maharana Bhupal Singh, who ruled Mewar from 1930 to 1955. Bhagwat Singh had three children — former Chittorgarh MP Mahendra Singh, Arvind Singh and a daughter, Yogeshwari.

A car belonging to the royal family inside the Udaipur Palace. (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

A car belonging to the royal family inside the Udaipur Palace. (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

The dispute is between the families of Mahendra and Arvind Singh and dates back to the 1980s. At the core of it is the Udaipur City Palace, a 16th Century architectural marvel with its grand arches, magnificent water fountains, and rich and vintage furnishings that’s the city’s most popular tourist spot.

Police stationed outside the gates of Udaipur Palace (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

Police stationed outside the gates of Udaipur Palace (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

The City Palace has three hotels — Taj Lake Palace, Fateh Prakash, and Shiv Nivas, all landmarks of Udaipur city. Arvind Singh’s branch of the family oversees all three properties. Apart from this, the Hindu Undivided Family property also comprises schools and the Samor Bagh palace, currently serving as Vishvaraj Singh’s residence.

According to palace sources, at the root of the dispute was Bhagwat Singh’s decision to lease out many properties of the royal family from 1963 to 1983, even selling his stake in some of them. In addition, he also set up a Trust, the Maharana Mewar Charitable Foundation, in 1969, donating to it the main portions of the City Palace as well as offering an endowment.

Arvind Singh currently heads the Trust. His father’s handling of the royal properties angered Bhagwat Singh’s son Mahendra Singh, who filed a lawsuit against him in 1983. Ousted by his father over the lawsuit, Mahendra Singh eventually went to settle at Samor Bagh, also part of the family estate.

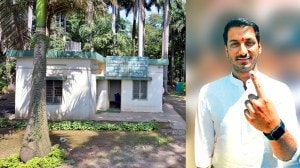

A temple inside Samor Bagh, the residence of BJP MLA Vishvaraj Singh Mewar, in Udaipur (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

A temple inside Samor Bagh, the residence of BJP MLA Vishvaraj Singh Mewar, in Udaipur (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

After 37 years of hearing, the Udaipur district court finally gave its ruling in 2020, equally dividing three properties — Shambhu Niwas Palace, the family residence inside the City Palace; Badi Pal, a promenade; and Ghas Ghar, once a storage space for fodder that’s now a cultural centre — between Bhagwat’s three children, says Mahendra Singh’s lawyer Narendra Singh.

Significantly, the court also considered the properties under the Mewar estate and the trust as HUF properties that will be partitioned according to the Hindu law. “Along with this, the court said that Mahendra Mewar, Yogeshwari and Arvind Singh will stay at Shambhu Niwas inside the City Palace for four years each from April 1, 2021,” he says.

Arvind Singh, who has been living at Shambhu Niwas for over 35 years, challenged this ruling in the Rajasthan High Court, which stayed the lower court order. It was after the death of Mahendra Singh Mewar earlier this month that his son Vishvaraj was ‘anointed’ as the head of the royal family of Mewar.

Lakshyaraj Singh at Udaipur Palace (Express photo by Parul Kulshrestha)

Lakshyaraj Singh at Udaipur Palace (Express photo by Parul Kulshrestha)

Soon after his ‘anointment’ in a ceremony at Chittorgarh, Vishvaraj and his caravan of nearly 1,000 people arrived at the gates of the City Palace but encountered police barricades. It was during this chaos that things took a violent turn. According to eyewitnesses, stones were pelted from both sides, with each one blaming the other.

On his part, Arvind Singh’s son Lakshyaraj has claimed he was trying to “protect” his own family, including, according to palace sources, his bedridden father. “Entering someone else’s property without permission is unlawful,” he said at a press conference he held on Tuesday, a day after the violence.

The City Palace’s Badi Pal entrance (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

The City Palace’s Badi Pal entrance (Express photo by Yogesh Mali)

Vishvaraj, meanwhile, claims he was prevented from doing his “social duties”. “I’ve never been as good at public relations as Lakshyaraj Mewar. I went to the palace to visit the Dhuni, which everyone is allowed to visit. I just wanted to fulfil the customs after the coronation,” he says.

Asked why he didn’t seek permission from the palace authorities, Vishvaraj points to the property dispute being pending in the Rajasthan High Court. “Until that’s settled, I have every right to enter the palace, which is part of the family,” he said. On the evening of November 27, temperatures lowered somewhat when four people, along with Vishvaraj, were allowed to enter the palace gates for the darshan at Dhuni.

Once upon a time…

Back at Samor Bagh, a white shamiana stands on the vast and well-manicured lawns, shimmering in the sun. Inside, hundreds of black chairs are lined up for the guests, all facing a stage.

On the platform sits a pink sofa — a raj gaddi for the “newly coronated” king. The whole setup bears an after party-look, with several men working to clean up the place.

On Wednesday, the palace grounds played host to hundreds of the people, all of whom had come to pay their respects to their new “Hujoor”. “This place was teeming then,” a palace guard says. “There was no place to stand.”

When the Constitution of India came into effect in 1950, all royal titles were abolished. The abolition of the privy purses in 1971 — a payment that was made to erstwhile royal families as part of their agreement to integrate their state with India — further eroded the standing of the former royals, making them emblematic of a bygone era in most parts of the country.

However, in the minds of the general public, and in their own, they continued to inhabit their older world with its rigid conventions and traditions – from customary coronations to grand Diwali and Ganesh Puja celebrations.

According to the established Mewar customs, a newly coronated ‘Maharana’ is expected to visit two temples – the family deity on the Udaipur Palace Grounds and the 8th Century Eklingji temple in Udaipur district’s Kailashpuri village, under whom the Maharaja of Mewar is meant to work as diwan (minister). The visit to Eklingji Temple marks the end of the mourning period — after which, the ‘Maharana’ swaps his white pagdi, or turban, meant for grieving for the traditional pink one that symbolises Mewar.

According to Ajatshatru Singh Mewar, a member of the royal family, one needs the support of 16 Umraos to become the Maharana in Mewar. Landowners of old, these Umraos and their families were considered the king’s primary support system. “The majority of the Umraos, barring a few, were present at the time of Vishvaraj’s coronation,” Ajatshatru Singh says.

“The crowd that followed him to the palace grounds on November 25 consisted of those who still consider Mahendra Singh Mewar as the rightful heir. Mahendra Singh was also crowned after the death of his father but he was ousted from the City Palace because of the legal dispute.”

The incident of this week seems to have turned the tide of public sympathy towards Vishvaraj and against Lakshyaraj. What seems to have fueled this public sentiment against Lakshyaraj is his absence at his uncle Mahendra Singh’s funeral earlier this month. Kamlesh Soni, a 55-year-old shopkeeper near the City Palace, said the city markets were shut down four hours after the news of the former MP’s death spread. “We all went to pay our respects to him. In the city and in the rural areas, Vishvaraj ji is the one who is respected as the Maharana,” he says.

Prakash Rajpurohit, 45, who owns a hotel near the palace, comes to Lakshyaraj’s defence. “Since Lakshayraj had claimed to be the heir of the royal title, allowing Vishvaraj inside the palace after the coronation would have meant that he accepted him as the next Maharaja. It was a way to display his power,” he says, adding, “But by keeping the palace doors shut, Lakshyaraj has made Vishvaraj famous, not just in Rajasthan but in the entire country.”

A new-age ‘prince’

It’s 7.30 pm, and a cold winter chill surrounds the City Palace. Lakshyaraj, dressed in a grey and red sweatshirt and a yellow T-shirt, sits in a grand visitors’ room that has hues of beige and red. Behind him are portraits of three men, all in traditional Rajputi attire – a white angrakha kurta adorned with beads, a cummerpatti (waistband), a white pyjama, red jootis and a pagdi, complete with swords hanging by their side.

The legend under Lakshyaraj’s portrait says “Maharaja” while next to him, his father’s portrait bears the title “Shriji”. The rooms also feature a portrait of Lakshyaraj’s six-year-old son, one of his two children, in full royal attire.

Only an hour earlier, Lakshyaraj had opened the gates of the palace, shut since November 25, to the public. Since this week’s incident, he’s held several press conferences and interviews, and now settles himself on a comfortable beige sofa for one more.

“Thousands of people marched with swords towards the palace,” he tells The Indian Express, furious at the entire episode. “When the doors were not open, they broke the three-layer barricades and tried to climb the palace walls. They made allegations of stone pelting but why don’t people ask them about the hooligans who were with them?”

Lakshyaraj maintains a very public image. A tech-savvy ex-royal with 1 million followers on Instagram, the 39-year-old has been invited to several talk shows all over the country and has been on magazine covers.

Lakshyaraj is married to Nivritti Kumari, a member of the erstwhile royal family of the princely state of Patna in western Odisha. Although he is yet to contest an election, Lakshyaraj is not averse to politics, admitting that it could happen “in the future”.

Asked why he didn’t attend his uncle Mahendra Singh’s funeral, Lakshayraj claims to have been threatened. “Our families aren’t on talking terms but I would still have gone for the funeral. But after receiving such information, it would have been a foolish thing to do,” he says.

There are challenges to being a royal, he says. “You will find good people but there will also be many who are envious and pull you down. I do have few close friends but things can get rough with so many expectations.” At least there, the two feuding cousins share common ground. Back at Samor Bagh, Vishvaraj says, “The public wants me to serve them. Being ‘Maharana’ is not only part of my family legacy but also a cultural legacy.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05