A time to remember: A museum that has many Partition stories to tell

An upcoming museum intends to be the repository of Partition stories

Updesh Bevli reading the letter from her classmate

Updesh Bevli reading the letter from her classmate

Updesh Bevli holds a yellowed letter carefully in her open palms and reads out a line from the faded pages. It is a letter from a classmate named Amena, written in September 1946, describing the rise of communal violence in Calcutta, the city they both lived in, as “a cats and dogs fight”. Bevli and Amena were only 16 years old then. “I have to locate the rest of them. I don’t know where they are. I was able to find only a couple of them,” she says. After attending the launch of the Partition Museum Project last week in Delhi, Bevli has begun searching for letters she had received around the time of Partition to donate to the museum, which will open its doors either in Delhi or in Punjab in 2017.

The idea of a Partition Museum was first proposed in the 1950s by veteran journalist Kuldip Nayar, but the wounds of the separation were still too raw. It would be another 65 years before author Kishwar Desai would start the Partition Project, but this time she was moved by a sense of urgency to create a physical space of remembrance of that fateful year. “Now is the time. There are very few people left of the Partition generation,” she says. Desai’s father, Padam Rosha was 22 and living in Lahore during Partition. He migrated to Jalandhar when the violence broke out, and is still haunted by images from that journey. “The most horrendous sight was that of people moving on foot. The poorest, the most helpless, old, sick, weak, and with hardly any belongings in the world — people were forced to move in long caravans. They were preyed upon again and again along the way. Robbed, abducted. And then, all this misery was compounded by the rains. It rained and rained and the floods came and thousands of these caravans were swept away,” he said at the inauguration ceremony. Rosha’s account will be part of the museum, which will feature stories of thousands of survivors that are being sent to the Project’s email id, thepartitionmuseum@gmail.com. These stories will be portrayed through oral testimonies, books, photographs, film, music and fine art.

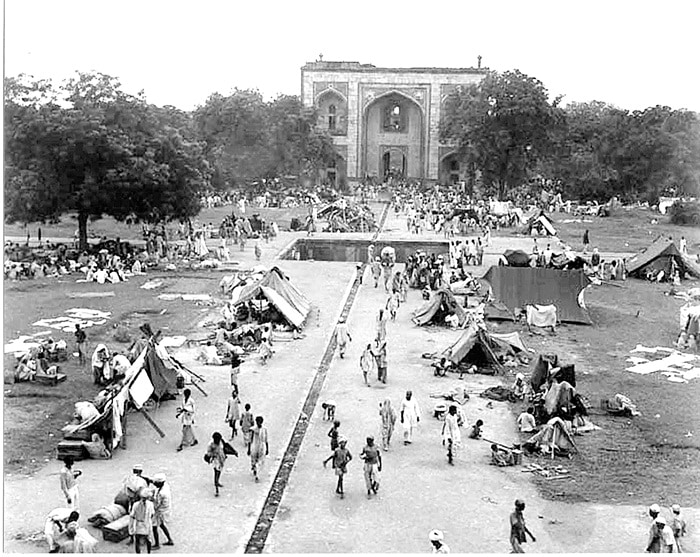

Refugee camps at Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi

Refugee camps at Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi

Soon after receiving that letter in 1946, Bevli would see a Muslim boy get stabbed to death from her balcony in a Hindu majority neighbourhood, Kalighat, an incident that she has never been able to forget. Yet, she speaks of a time before the bitter Partition as one of harmony. “I was a Sikh and I attended a Muslim school called Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ High School in the early 1940s. We were not unwelcome, we never felt strange. We made friends, played sports, ate at the same table. That was the happiest time,” she says. Bevli, now 85, left Calcutta when she got married to an Indian Air Force officer in 1950. She travelled across India with him, until they settled in Delhi 50 years ago. After earning her PhD at the IIT, Delhi, Belvi has had a successful career as a child psychologist.

Sunaina Anand, director of Delhi-based art gallery, Art Alive, recalls how her grandfather, Masudan Lal Puri, who passed away in 1997, had been a prosperous merchant in Shekupura near Lahore in Pakistan. Puri owned six general stores, all of which he lost. He barely managed to escape. “He hid for many days inside a water tank when the riots started. A lot of people knew him and came looking for him because he was quite popular. He watched all of his shops being gutted. That is when he thought that he needed to get to Delhi,” says Anand, 50, who contributed her grandfather’s story and a photograph to the museum. It had, however, been the foresight of a Muslim friend that prompted Puri to send his wife and six daughters ahead of him to Delhi. “He had a very dear Muslim friend who told him that he felt something was going to go wrong and that he should send the girls away. This was 20 days before the violence began. The family was to attend a wedding in Delhi, so the women left early,” she says.

Photos of Bevli and her family

Photos of Bevli and her family

Puri would later join them in one of the refugee camps in Delhi in 1947. After selling whatever he could get hold of on the streets, he formed a community of merchants who had lost their businesses during Partition. “He said they must go to Nehru and ask for proper shops. He started making an association of refugees. They would sit together and draft appeals for some sort of permanent area,” says Anand. That was how Delhi’s now thriving Janpath market was born. Puri himself opened an import business and a general store in the market. He went on to work in the shoe industry, where he owned five stores across Delhi, and was the main distributor for many big brands. “When he would narrate these stories, he would tell us never to lose hope. He started from scratch and worked his way up. Nothing is impossible, he’d say,” says Anand.

While Desai says such stories of remarkable human resilience will hold a prominent place in the museum, she also recognises the fear of what sharing memories of the biggest migration in human history, and one of the most violent events of the 20th century could bring. “There are still people who say we don’t want to talk about it or go there. There is a fear that there could be some violence again because they’ve seen so much of it already,” she says.

Yet, remembrance brings with it redemption too. Bevli’s daughter Poonam, 57, visited Rawalpindi, the hometown of her father and maternal grandparents, this year. “I found a beautiful, lush country. The people were warm, there was no bitterness. But when I went to Rawalpindi, my own emotion was one of loss. I felt the anguish my parents had left behind. I wept and wept for them, for the life that they had left behind. The feeling was no way connected to the people; it was just for my parent’s loss,” she says.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05