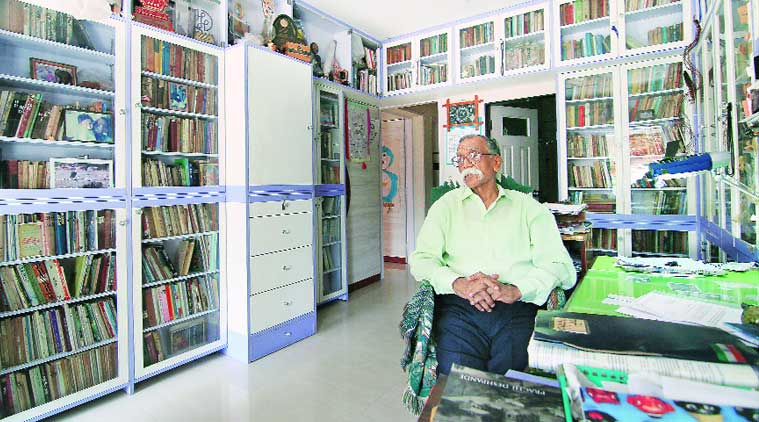

There is a caricature of a four-legged animal with a large moustache on the wall of 76-year-old Jnanpith award-winner Bhalchandra Nemade’s study in his house in Santacruz, Mumbai. It’s captioned Aabu, the name his granddaughter fondly calls him by. This little bit of whimsy is in sharp contrast to the way the veteran novelist, poet, critic and retired professor from Mumbai University is perceived. His debut novel Kosla (Cocoon, 1963), the story of a boy from rural Maharashtra who goes to Pune for an education, changed the course of the Marathi novel. Since then, Nemade’s ideas of nativism, the opposition of globalisation, and the cynicism of his characters has garnered a steady following. Kosla was followed by four novels: Bidhar and Hool (1967, published as one novel initially and later identified as two separate novels), Jarila (1977), Jhool (1979) as well as two collections of poems, Dekhani and Melody. In 2010, he released the first part of his forthcoming quartet of novels, Hindu — Jagnyachi Samruddha Adgal (A rich clutter of living). He is currently working on the second volume. Excerpts:

After you were awarded the Jnanpith award, your comments about Salman Rushdie and VS Naipaul and Rushdie’s retort made news. But once, you had praised him for Midnight’s Children. What made you change your opinion?

I have praised Midnight’s Children for its creative use of language and it is undoubtedly a great novel. But I object to the portrayal of various civilisations by these writers, and to their appeasement of Western civilisations. Why don’t you write about the place where you live and belong to? They may argue that it is their choice of subject. But then, we as readers also have the choice to have reservations about their portrayal of these subjects.

Story continues below this ad

You are known to be an advocate of nativism or Deshivaad. Some people are infuriated by the idea while others respect it. Where and how did Deshivaad come about?

I won’t be able to pinpoint the exact time, but ever since I started writing and thinking about what was being written in Marathi at the time, I began to feel that most of the works were like an appeasement of Western culture and were blindly copying the West. These works were disconnected from our society and culture. I come from a small village in the Satpura ranges; in our village there used to recitals of the Mahabharata, and the Puranas. We knew the works of Maharashtra’s sant kavis by heart, we grew up listening to folklore. Over the years, the contrast between what was being written as I was growing up, and what our roots told us, led me to believe that any form of artistic expression, particularly literature, can only flourish in its own soil, own language — and there is no exception to this the world over. It cannot sustain itself on borrowed themes. When we have a rich tradition of Ghalib, Mir, Kabir and Tukaram, why look outside for inspiration?

Some may compare this belief to the ideologies of certain nationalist groups or language fundamentalists.

Yes, it is possible that Deshivaad is seen in the same way. But every thought has its own autonomy. The perspective of some fundamentalists, and mine, may walk together, but it is important to know at what point our paths diverge. I believe that Ghalib is one of the greatest modern poets, but do they feel the same? When I say that every one of us belongs to the Hindu culture, I am not talking about the religion at all. One of the reasons I feel Vijay Tendulkar’s Ghashiram Kotwal (1972) is great because it uses all the native forms of art and literature. This is where the fundamentalists and I walk away from each other. People may find similarities in our love for native language or culture but they stem from different origins and have different motivations.

Deshivaad opposes the wave of globalisation — it does not stop you from acquiring knowledge from other languages or cultures.

The protagonist of your first novel, Kosla, Pandurang Sangvikar is a cynic. Many contemporary writers at the time, especially those from the Little Magazine movement in Marathi, were cynical, non-confirmist and non-populist. Was that source of Sangvikar’s attitude?

Yes, it is true. Pandurang Sangvikar is very cynical and so were the likes of Manohar Oak, Arun Kolatkar, Dilip Chitre, Ashok Shahane and several other talented writers of that time. I believe that the attitude of questioning everything came as a reaction to the established writers of that time. It also provided new writers with a way to distance themselves from the society they live in. These writings were a reaction to the monopoly of the literary world; it led to our growth.

Story continues below this ad

Sangvikar is cynical. Changdeo Patil from the next four novels (Hool, Bidhar, Jarila and Jhool) seems to compromise and adjusts to the situation around him. And Khanderao from your latest work, Hindu, is searching for his roots. Have you personally gone through the same transformations?

Yes. I believe that plots and characters have to be honest to the writer’s perspective and politics, and also to what is going on around him or her. These things can’t be borrowed or stolen. At the end of Kosla, Sangvikar comes to realise that there is a battle between freedom and equality, and he will have to adjust to the world. And so, Changdeo Patil is born. He has to become a draught animal, like a bullock, and so the names Jhool and Jarila are used, which refer to a bullock. There is an internal rebellion as I make these adjustments.

The Little Magazines, in Marathi and even in other languages, captured themes that were absent from popular literature. Do you think the young generation of writers are doing the same?

They’re doing it better than we did. At that time, ours was the only group, and there was only a handful of us. But today, people are writing from all walks of life, all sections of society. Issues of the oppressed classes, of tribal populations, of youth from rural areas. The young generation is writing about their frustrations, the adjustments they have to make to survive, their struggles, their rebellion. What is the quality of the work is another issue, but the question should be this: are they able to put their finger on the pulse of what is happening around them and are they honest to that reality? I believe poets, novelists, playwrights of the young generation are doing so. I’m not very comfortable with the internet, blogs and social media. But from whatever little I can gather, I feel even this sphere of artistic expression is vibrant.

You have fiercely criticised awards and award ceremonies. You’ve also criticised cults which are formed around writers. But you have accepted the Jnanpith award and some others. And there is ‘Nemadpanth’ — a cult formed around your works. What do you think about this?

I do not like the idea of such cults but if people with similar viewpoints come together, the formation of such cults is but natural. I have observed that as one grows old, one starts turning into a lifeless institution. Even I fear I am becoming one. I am still against the awards for which people have to apply and I have never applied for an award. But people start thinking of you as an arrogant man.

Do you think the rise of right-wing powers has affected public discourse?

Yes it has, deeply. I also believe that this is a cycle. Public discourse itself has resulted in the rise of these powers. In the past, the majority believed that right-wing organisations were backward. But the alternatives available to them failed to deliver and steer a public discourse. The result is before us and if one believes in the democratic process, one has to accept this.

Story continues below this ad

You have criticised the short story form. Why?

It’s not just about the length of a work. For example, a couplet in a ghazal or an abhang by Tukaram or a doha by Kabir contain thoughts, arguments, which even lengthy forms of writing cannot accommodate. I oppose a culture of writing a story on Monday, finishing it by Friday and waiting for royalties without achieving any depth. There have been great writers — Premchand, Phanishwar Nath ‘Renu’, Rabindranath Tagore, Saadat Hasan Manto — who have used the short story form to create some of the finest literary works from India. One has to accept the greatness of Leo Tolstoy, Guy de Maupassant, Anton Chekhov. I have reservations about the lack of the conceptual and emotional expanse of a work and not the length per se. If Manto had written a novel, it would have been one of the greatest in the world.

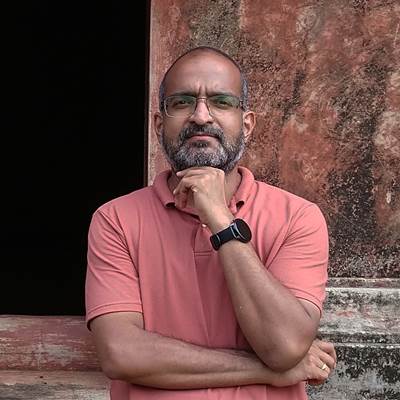

Marathi writer Bhalchandra Nemade

Marathi writer Bhalchandra Nemade