Handbook of the Indian Constitution review: A Site of Struggle

A fine collection of thoughtful essays on the Indian Constitution, but this is not a handbook as advertised

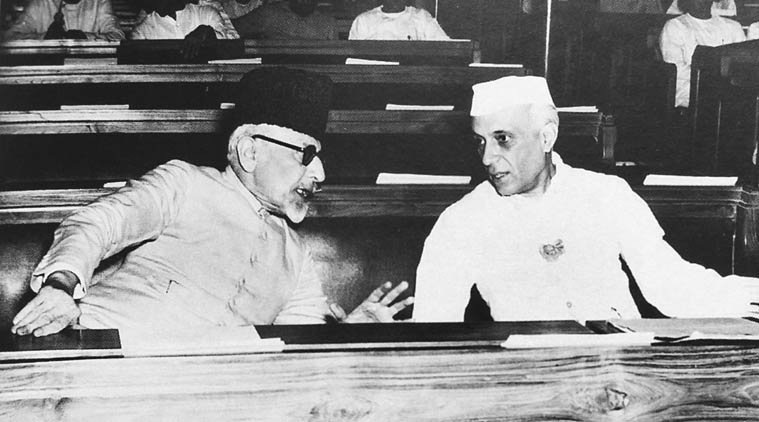

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru with Maulana Abul Kalam Azad at the Constituent Assembly session of 1946 (Source: Express Archive)

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru with Maulana Abul Kalam Azad at the Constituent Assembly session of 1946 (Source: Express Archive)

The Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution

Authors: Sujit Choudhry, Madhav Khosla and Pratap Bhanu Mehta

Publishers: Oxford University Press

Pages: 1072

Price: 960

Having been asked belatedly to contribute to this book by a disturbingly peripatetic editor, here’s a caveat: I may not be the best person to review it. The Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution broods a galaxy of writers: two former Supreme Court judges, 14 practising advocates (including a pupil barrister), 22 teaching abroad, three from the Centre for Policy Research from which this book was born, seven students, the rest academics of various description. What an incredible team to examine the Constitution “as a charter through which an ancient civilisation was set on the road to modernity and social reform” and to “guide the fluidity of Indian Constitution law”! Meant for students and lawyers, it might belie the expectations of both as they journey through the uneven contributions of the book — at times, strikingly intense, and at times, somewhat ordinary.

Indian constitutional law suffers from a lack of serious writing. MC Setalvad’s Indian Constitution 1950-65 portrays the brilliance of a practising attorney general. HM Seervai’s Constitutional Law was incomparably analytical before it became acerbic and died for want of editions. Mohammad Hidayatullah’s project for a Halsbury on constitutional law failed. Indian academics like PK Tripathi and Upendra Baxi provided sporadic constitutional consciousness. The new law schools have produced brilliant researchers and writers without the help of national law school teachers (including the ubiquitous Madhava Menon), along with Indian scholars abroad and, of course, foreign scholars offering sustained and unsustained interest (HCL Merillat, Marc Galanter). This book is by the new “brood”, as I call them, and it showcases their most imaginative scholarship. No anthology of essays on India’s Constitution is to be more treasured than this book. But beware of the title, it is not a handbook of the Indian Constitution — just a collection of damned good essays by thoughtful writers.

There are two parts to Indian constitutional law. The first is constitutional legal doctrine, entirely been created by lawyers and judges. Academics have played no role whatsoever. Decades ago, there was some critique by the Indian Law Institute, which collapsed as it was under judicial control. Indian judges like to be praised and resent non-appreciation to the same extent as Supreme Court judges do not like to be called “Your Honour”, preferring “My Lord”. The second aspect of the actual working of the Indian Constitution is in the hands of politicians, administrators, businessmen, corrupters, the corrupted and the like who feel they can buy and sell parts of the Constitution. There is no point pretending that there is some kind of morality binding the Constitution. This is what we preach when we use words like “constitutional morality” or the “real underlying of the Constitution”, as this book urges. Of course, as against constitutional predators, there are good people faced with horrible choices to which they succumb. This book is blind to those concerns.

We hope, we pray, but India’s Constitution (peace be upon it) is sinking, exploited to the maximal extent in every unscrupulous direction — rigged and violent elections, non-functioning of Parliament and Assemblies, a judiciary which suffers from ordinariness subject to exception, a violent and sexist society, vulnerability at every level and rampant corruption. Spin as many doctrines as you like but if you can’t see the collapse, you are blind. I am not saying that the rule of law texts (including institutional moralities) should not confront the political, bureaucratic and judicial texts and pull them up. They must. But it’s going to be an ever more daunting task to avoid shreds of the Constitution from being bought and sold, humiliated and destroyed. Ruma Pal (quoting Seervai) reminds us, like a candle in the wind, that power is not property.

I now turn to the book. Was such a thin discussion on administrative law necessary? Should fiscal federalism have been left incomplete? Or trade and commerce limited to issues of compensatory tax? Is there any point in picking out an unimportant case on “pith and substance” for a lecture on legislative competence? Can the large canvas of service law be impressed with such angularity? Can we say that from 1980 the Supreme Court, rather than constitutional amendments, became the arena of change? And what of the reservation amendments (1995-2003)? Is there really a growing respect for international law, or is it pick and choose? My friend Harish Salve has a bone to pick on the Mullaperiyar case, which we both lost. Isn’t the old controversy about tribunals over? Baxi’s extravaganza always delights and should find its place in constitutional history.

I read and continue to read the book. What makes the going difficult is its uneven tone — it’s sometimes comprehensive, sometimes dilatory and sometimes, a researcher’s personal agenda.

For me, the Constitution is the site of struggle — to preserve it, make something of it and allow those engaged in a struggle for dignity and opportunity to use it.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05