Don’t Look Back in Anger

Why an outspoken memoir by an LTTE fighter and head of its women’s political wing has the Tamil community divided.

Thamilini; a Sri Lankan soldier looks on as a town goes up in flames in Putumatalan in 2009. (Photo: Reuters)

Thamilini; a Sri Lankan soldier looks on as a town goes up in flames in Putumatalan in 2009. (Photo: Reuters)

The northern region of Sri Lanka is one of the most beautiful places on earth. Sea drenches the edges of its green-spangled plains from three directions, except the south. Roads dissect lagoons in thin, straight strips to reach small, sparsely populated villages or bustling towns that appear orderly and surprisingly clean. I was there last month. It was hard to imagine that a war was fought in that land six years ago. The scars are there, no doubt, to remind us that war is misery, destitution, destruction and, finally, death.

Six years ago, this minuscule parcel of land, where hundreds of thousands of civilians were hemmed in, was pounded by heavy pieces of artillery, bombarded from air and targetted upon by missiles. The stranded had no other option except to wait. If the Sri Lankan army bayonetted them or shot them from close range for the crime of being born Tamils, the Tigers, one of the most ruthless terrorist organisations the world has ever seen, coralled them and used them as human shields.

That was a dirty war — perhaps the dirtiest in recent history. Velu Pillai Prabakharan, the supremo of the LTTE, was an unrepentant killer and the list of murders and assassinations committed under his orders is almost endless. On the other hand, the Sri Lankan government was always ruthless in dealing with violent dissent. In the 1970s and 1980s, they killed the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) activists without any compunction — almost all of them Sinhalese and in the prime of their youth —in tens of thousands. With the Tamils, too, they adopted similar tactics.

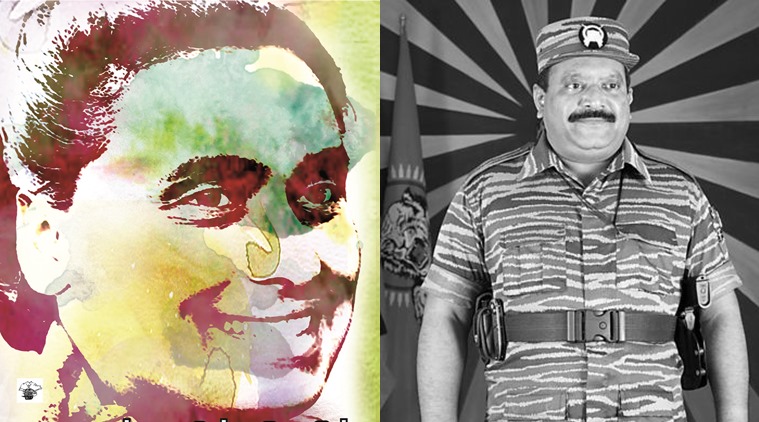

Cover of the book (L); and LTTE head Prabhakaran.

Cover of the book (L); and LTTE head Prabhakaran.

There are several recent books that speak about this sordid period in the history of Sri Lanka. Gordon Weiss, who had a ringside view of the war as the UN spokesman in Colombo, wrote a gripping account of the war and its genesis in a book called The Cage (2011). Frances Harrison, who was the BBC correspondent during the war, recounted the survivors’ tales in Still Counting the Dead (2012). Samanth Subramanian writes the stories of this war in This Divided Island (2014) in splendid prose. If KM Desilva’s Sri Lanka and the Defeat of the LTTE (2012) gives us the Sinhalese perspective, N Malathy’s A Fleeting Moment in My Country (2012) tells us the experience of a Tamil volunteer who spent her time in the war zone during the last days of the war.

Why then is S Thamilini’s book in Tamil, Oru Koorvalin Nizhalil, (In the Shadow of a Sharp Sword) unique?

Thamilini was an idealist school girl who went on to become the head of the LTTE’s women’s political wing . In 1991, she was heading the school band which played during the funerals of Tamil fighters. Moved by that sight, she joined the movement. She was a member of many fighting formations and took part in important battles. She moved up the ladder and became the head of the women’s political wing in 2000. She fought for the rights of women within the movement and achieved some success. She was the political face of LTTE women in international forums.

In 2009, with the battle ending in a catastrophic defeat for the LTTE, she discarded her uniform, mingled with the civilians and hoped to get away. But she was identified and arrested. She spent a few years in jail and was released in 2013 with the help of a doughty Sinhalese human rights lawyer. She found in jail that human beings, even the Sinhalese, want to live peaceably. She stumped death on countless occasions during the war. But last year, death overcame her at 43 in the guise of cancer. She fully knew about the disease stalking her and she thought she should tell the Tamil people a few truths. The result is this insuperable book.

Tamil refugees from Jaffna at a camp in Vavuniya. (Express photo by Praveen Jain)

Tamil refugees from Jaffna at a camp in Vavuniya. (Express photo by Praveen Jain)

She is unafraid to answer the question every Tamil was asking: What was the reason for a movement, which was built with so much hope and on the lives of hundreds of thousands of persons to become, finally, an insignificant zero? She answers several such uncomfortable questions in the book.

It is not that Thamilini has come to hate the LTTE supremo. It is clear from the book that her admiration for Prabhakaran remains unsullied. But she has been critical of the indefensible stands taken by him during his last years. For instance, she narrates the conversation she had with another woman commander, Vidusha, about shooting Tamil civilians in the leg in order to prevent them from escaping to areas controlled by the Sri Lankan army. In the words of the commander, “Our boys ask: How can we shoot at our fathers, mothers and siblings? We can as well train the guns on ourselves and die.”

The dilemma of the LTTE was that it was flush with weapons but didn’t have enough persons to use them in battle. The solution found by the leadership was to pressgang unwilling youngsters, many of them minors, and send them to battle without adequate training. That she could never reconcile herself to this unforgivable act comes out clearly in the book. She speaks with obvious agony when she says that the very people who loved the Tigers had started hating them intensely because of the unrelieved misery caused by war.

She also tells us how the Tamil society received the women fighters of the LTTE when they returned after the defeat of the movement. “Instead of returning like this, they should have bitten the cyanide capsules” was the reaction. She says her experience has taught her that one cannot do any good by taking up arms or seeking revenge and it is peace that will lead to a society’s progress.

The book has created a minor storm in Tamil circles. An overwhelming majority of Tamil readers have welcomed it. Diehard LTTE supporters have, however, started a campaign that the book is at least partially ghost-written and the passages that criticise the movement are insertions after her death by the enemies of the movement. But any neutral person who reads her book will immediately feel the searing heat of the work. The book deserves a wider audience and needs to be translated into English.

PA Krishnan is a writer in Tamil and English.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05