Chasing monsoon for 150 years: The origin story of India Meteorological Department

It has been a long journey from those early days and IMD now has evolved into a massive organisation, running hundreds of permanent observatories and thousands of automatic weather stations, covering every nook and corner of the country.

While weather forecasting remains its main raison d'être, IMD now provides a variety of related specialised services that are sought by a vast range of agencies. (File Photo)

While weather forecasting remains its main raison d'être, IMD now provides a variety of related specialised services that are sought by a vast range of agencies. (File Photo)Two monstrous cyclones in 1864, one striking Kolkata and the other hitting the Andhra coast, killed more than one lakh people. The loss of lives in the Kolkata cyclone, possibly the most destructive one till then, alone was estimated to be over 80,000. Two years later, in 1866, India faced severe drought and famine, pushing scores of people into malnutrition and deaths by starvation.

Though events like these were not uncommon in India in those times, the severity of these particular calamities, more than anything else, exposed the lack of a system of monitoring atmospheric parameters and foreseeing their changes. It is these events that triggered the eventual setting up of the India Meteorological Department, which on Monday, January 15, is entering its 150th year of existence.

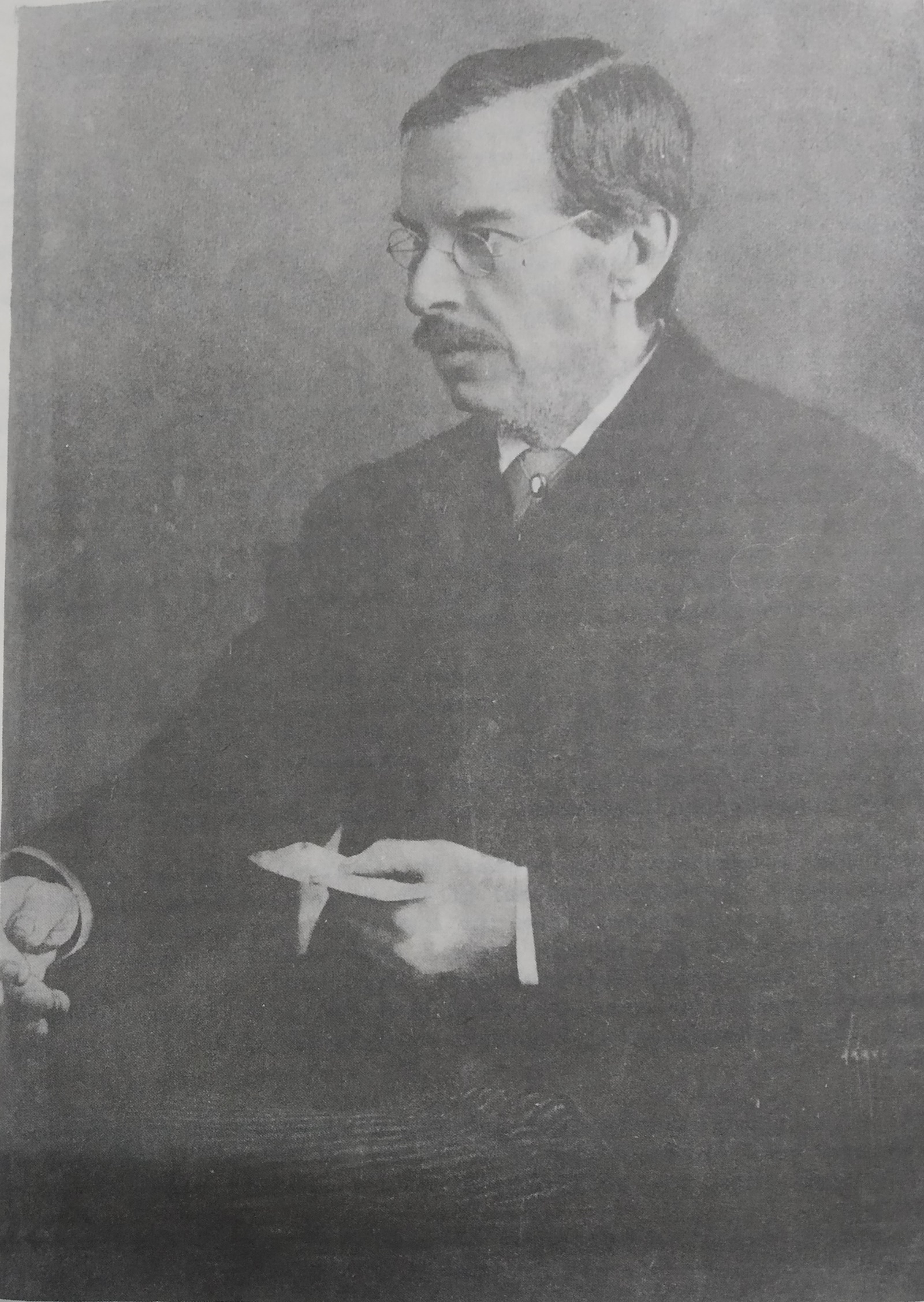

HF Blanford , first Imperial Meteorological Reporter, took charge as he landed in India on 15th January, 1875.

HF Blanford , first Imperial Meteorological Reporter, took charge as he landed in India on 15th January, 1875.

Though meteorological observations were being made from several observatories at least from the 1850s, these were being done largely by amateurs or the disparate wings of the British colonial system, including the military and the survey office. The Asiatic Society of Bengal, which had been publishing some of these observations in its journal, was among the first to push for the setting up of a separate office. It was on January 15, 1875, that the IMD officially started functioning, employing the services of just one person, Englishman HF Blanford, who used to be called the Imperial Meteorological Reporter. His job was to systematically study the climate and meteorology of India, and use this knowledge for weather forecasting and issuing cyclone warnings.

It has been a long journey from those early days and IMD now has evolved into a massive organisation, running hundreds of permanent observatories and thousands of automatic weather stations, covering every nook and corner of the country. While weather forecasting remains its main raison d’être, IMD now provides a variety of related specialised services that are sought by a vast range of agencies. Whether it is conducting general elections or examinations, sporting events or mountaineering expeditions or organising a big function or a space launch, there is hardly any major activity that happens without the inputs of the IMD. These, apart from the several regular forecast and advisory services for agriculture, railways, airways and ships, power plants, fishing community, water management agencies and the like. Climate change research, and assessment of risks and vulnerabilities, is another major IMD preoccupation.

“Weather affects many of our activities, and it is not surprising that the IMD is now called upon to provide its services across several sectors. It is what is expected from a country’s weather office. We are constantly upgrading our skills and capabilities, so that our information continues to be useful,” IMD director general Mrutyunjay Mohapatra said.

Many of these services are recent additions to IMD’s work profile. Rajan Kelkar, 80, who served at the IMD for 38 years till his retirement as the director general in 2003, vividly remembers the invite he received from K R Narayanan, the then President, in 1999.

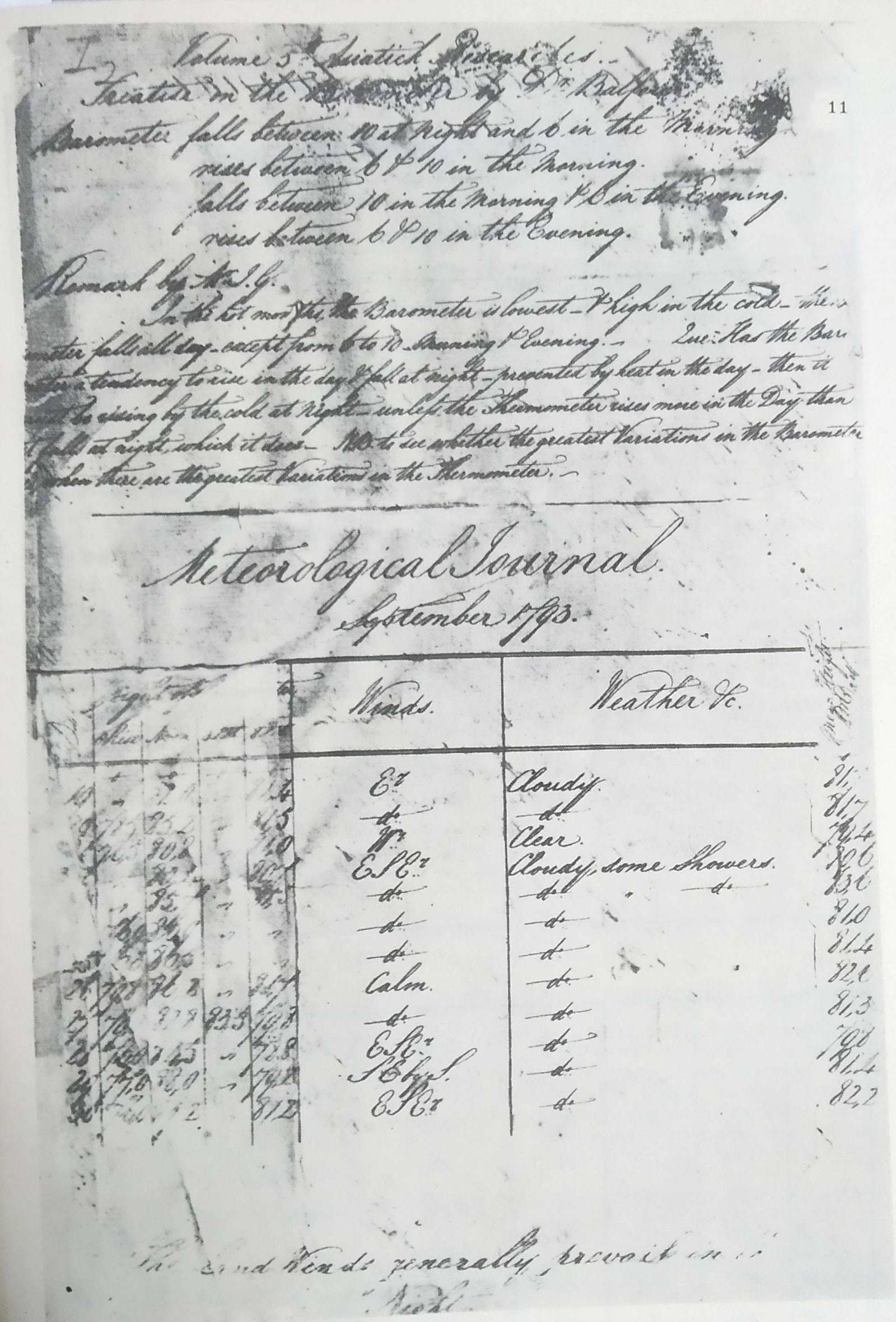

India’s first meteorological observation from Madras Observatory, dated September, 1793.

India’s first meteorological observation from Madras Observatory, dated September, 1793.

“President Narayanan was alone, seated on a sofa. He asked in great detail about the monsoon forecast and wanted to understand the ‘right’ time to conduct the general elections in 1999. At the end of 30 minutes, the President informed me to expect a call from the office of the Election Commission of India (ECI),” Kelkar recalled.

Within a few days, Kelkar met with Election Commission officials and made a presentation. Since then, the dates of the general elections, and also other state elections, are invariably decided after taking inputs from the IMD.

M Rajeevan, a former Secretary with the Ministry of Earth Sciences and an expert on Indian monsoons, has a similar fond recollection. As per IMD records, October 28, 2008, remains a heavy rainfall day, following the onset of the northeast monsoon. It was also the day that India launched its first space mission to the moon, Chandrayaan-1. Rajeevan led the team that predicted favourable weather conditions over Sriharikota at the time of the launch.

“Due to the approaching northeast monsoon, frequent thunder events were being reported during the days leading to the launch date of Chandrayaan-1. Based on simple physics and the local weather forecast, that indicated light rainfall during morning hours and thunder post afternoon, my team assured ISRO of a thunder-free window at the time of the launch. As predicted, there was no thunder and the launch was successful. It rained while we were packing to leave later in the evening,” Rajeevan said.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurating the weather radar at Delhi’s Safdarjung on 13th September, 1958.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurating the weather radar at Delhi’s Safdarjung on 13th September, 1958.

ISRO rockets are rain-proof but strong winds and thunder are not conducive conditions for a launch.

One thing that has remained largely unchanged over the last 150 years is the IMD’s quest to understand and predict Indian monsoon with increasing levels of efficiency. The monsoon system has always been extremely complex, but under the impacts of climate change, it has become even more erratic and difficult to predict. The last 15 years have seen a major improvement in IMD’s capabilities and it has shown up in its forecasts.

Kelkar said the obsession with the monsoon began with the start of the IMD, and early British meteorologists were flummoxed with what they experienced in their early days in India.

“Experiencing it for the first time, the early British officers serving at the department were amused by the monsoons. They wrote poetic and essay-like monsoon forecasts,” he said. IMD’s first long-range monsoon forecast was made in 1886 and, quantitatively, was a good one.

But IMD needed more stations and more people to work on monsoons. It even began to recruit Indians in officer ranks. The first Indian to be picked up for higher positions was Lala Ruchi Ram Sahni, who was shifted from Lahore to Kolkata, and offered scholarship, in addition to his salary, to continue studies at the Presidency College. However, Sahni, who happens to be the father of famous botanist Birbal Sahni after whom the Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleosciences in Lucknow is named, left IMD within two years due to differences with his English boss John Eliot, who had succeeded Blanford.

Among others who served at the IMD office in Kolkata later was Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, one of India’s best-known statisticians. Mahalanobis also stayed at IMD for a short-period, but left his bosses and the government officials impressed. One of his early works at IMD was a paper predicting monsoon floods in Mahanadi and Subarnarekha rivers. It was the presence of Mahalanobis that made Rabindranath Tagore, a close friend, a frequent visitor at the Alipore Meteorological Observatory. IMD archives take pride in recalling that many of Tagore’s poems were written under the banyan tree in the campus of this observatory.

The study of monsoons made major strides under Gilbert Walker who became the new head of IMD in 1903. A physicist and mathematician, Walker was the one who discovered the large-scale oscillations in atmospheric circulations, and its likely impacts on Indian monsoon and weather events around the world. It was the first and the most important discovery that laid the foundations of modern understanding of the El Nino phenomenon.

But monsoon prediction remained a tough nut to crack. Even during Walker’s 20-year tenure, some major droughts could not be predicted accurately. IMD forecasts were, however, still useful because the monsoon followed a relatively stable frequency cycle and was not as erratic as it is now. In the last one decade, however, monsoon prediction has improved several notches, and in quantitative terms, the IMD has got its forecast right in most of these years. Much more needs to be done in predicting the regional variations and the extreme events.

IMD has had much bigger success with the prediction of cyclones, however, which happened to be one of the main triggers for its establishment 150 years ago. Starting with the 2013 Phailin, the death toll from cyclones has come down to a minimal level. Earlier, cyclones those powerful could have easily killed hundreds or thousands of people. The credit has gone to IMD’s forecasts, combined with efficient evacuation measures put in place by local administration.

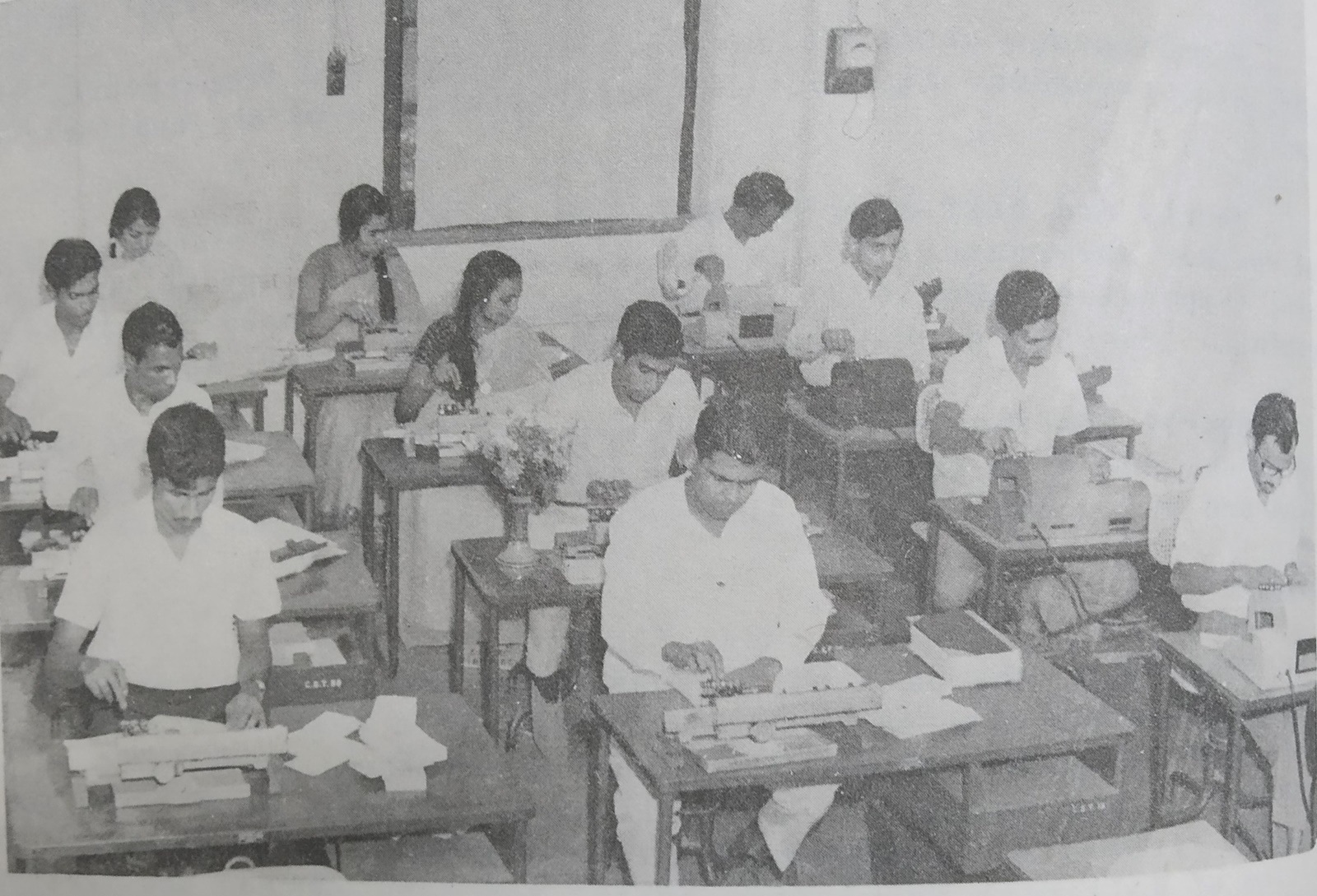

Staff involved in meteorological data punching , IMD, Pune. Cabinets used to store punched cards. Till 1975, over one million punched cards were archived at the Data Centre in IMD, Pune.

Staff involved in meteorological data punching , IMD, Pune. Cabinets used to store punched cards. Till 1975, over one million punched cards were archived at the Data Centre in IMD, Pune.

Mohapatra, who specialises in cyclones and was posted in Bhubaneswar during the 1999 Odisha super cyclone, said that event was his lowest point as a meteorologist.

“But that was also the turning point for IMD’s cyclone forecast capabilities. We made massive investments in time, manpower and technology, with the intent that something like this must never be repeated,” he said.

IMD’s cyclone forecasts now serve not just India but the entire neighbourhood, with as many as 13 countries in the region operating their cyclone management systems using these forecasts.

With its enhanced capabilities, IMD is now also playing a more active role at the global level. Nearly six years ago, the IMD, Pune, was recognised as the Regional Climate Centre for South Asia, under which the department issues seasonal climate outlook, monthly and seasonal El Nino and Indian Ocean Dipole status bulletins and prepares consensus monsoon forecasts for South Asia.

IMD operates three Regional Specialised Meteorological Centres each for tropical cyclones, severe weather and flash floods. In June last year, Mohapatra was elected as the third Vice President, WMO.

“In recent years, IMD’s role has been increasing and is also being recognised globally. It is a big responsibility,” Mohapatra said.

IMD has partnered to contribute to the United Nations’ ‘Early Warning for All’ programme, for which 30 countries have been identified. India has a defined early warning system, supported by essential infrastructure and technology but nearly 50 per cent of the countries in the world lack this facility.

“IMD will be working as the Peer Advisor for Bangladesh, Maldives, Mauritius and Nepal, works of which have commenced. IMD will help establish and calibrate instruments, start early warning forecasting and allied capacity building,” Mohapatra said.

But in the face of climate change, IMD needs to keep upgrading its skills and capabilities. The rise in the severity and frequency of extreme weather events is already visible and expected to worsen rapidly. Detecting, predicting and forecasting such events, especially estimating their impact over small areas, is extremely challenging with the present-day models.

“In order to detect these meso-scale severe weather events, there is a need for denser observational networks and frequent recording of observations. Here, we need to work with state governments in a private-public partnership model,” Mohapatra said.

Greater collaboration with universities and research institutions can foster better research and help IMD, says Rajeevan.

The role of IMD has diversified and increased many folds with services extended to the agriculture, aviation, disaster management, energy, health, hydrology, power, tourism and other sectors. In future too, the IMD will keep receiving service requirements and it will only keep increasing in the coming years. The challenge before the IMD would be dealing with unscientific and unreasonable demands, says Kelkar.

In future, Kelkar dreams of seeing IMD grow and become a union ministry by itself.

“The IMD serves the whole country and my futuristic wish is to see the IMD, with its own identity, become a ministry,” Kelkar says in the closing.