Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Beyond representation: Role of women as voters in seven Assembly polls in 2022

Barring Gujarat, all the seven states that went to the polls this year saw the female voter turnout rise.

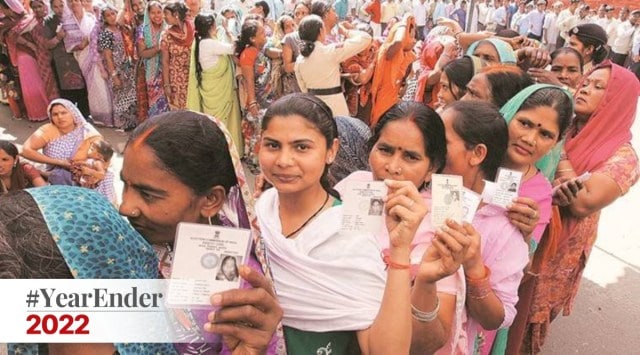

Even though parties fielded fewer female candidates than male ones, women played a key role in determining election results. (File)

Even though parties fielded fewer female candidates than male ones, women played a key role in determining election results. (File) Seven Indian states had Assembly elections in 2022. While five of them—Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Punjab and Goa—went to the polls early in February and March, Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh voted in November and December.

While discussions after the elections revolved chiefly around winners, losers and the number of seats and government formation, the role of women, not only as nominees, but also as voters was was less talked about. Even though parties fielded fewer female candidates than male ones, women played a key role in determining election results.

Let us take a critical look at the turnout of women in the seven states that witnessed elections, and the possible reasons behind it. In doing so, we borrow data from the Election Commission of India (EC) and Lokniti-CSDS, a think tank that studies democratic and electoral politics in the country.

The numbers

Article 326 of the Constitution grants every adult Indian citizen the right to exercise their vote, irrespective of gender, caste, religion or region. “There is a clear trend of increasing women’s electoral participation in the Assembly elections … it is not episodic,” said Sanjay Kumar, professor and co-director at Lokniti who has closely studied women and politics in India.

In the past two Assembly elections—2017 and 2022—the turnout of women voters were higher than that of men in all the seven states except Gujarat.

Uttar Pradesh

According to Lokniti-CSDS data, when the turnout in the two elections was about 61 per cent, the percentage for women voters were 63.46 and 62.27 per cent respectively. This is significantly higher than the percentage of men who voted (59.31 and 59.39 per cent, respectively).

Uttarakhand

In Uttarakhand, 68.72 and 67.16 per cent of female voters turned out to exercise their franchise in the 2017 and 2022 elections respectively.

Manipur & Goa

As per Lokniti-CSDS data, 87.99 and 90.51 per cent of female voters cast their votes in the two elections in Manipur, whereas 77.01 and 80.96 per cent of female voters turned out in Goa in 2017 and 2022 respectively

Punjab

Although very marginal, there lies a difference in the percentage of male and female voters in the Assembly elections in Punjab. While 75.88 per cent of men voted in 2017, the turnout for women was 77.9 per cent. In 2022, this difference reduced, with 71.32 per cent of male voters and 71.9 per cent of female voters exercising their franchise.

Himachal Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh presents an interesting case; female voters’ turnout exceeded that of their male counterparts in the past six elections. According to a report in The Indian Express, “the polling percentage of women and men electors was 72.2 and 71.23 per cent in 1998, 75.92 and 73.14 per cent in 2003, 74.10 and 68.36 per cent in 2007, 76.20 and 69.39 per cent in 2012 and 77.98 and 70.58 per cent in 2017”. And in 2022, 76.8 per cent of the female electorate voted, as against 72.4 per cent of male voters.

Gujarat

One would, however, witness a slightly different scenario in Gujarat. According to the Election Commission, of the 3.16 crore voters who exercised their franchise in the 2022 Assembly polls, 66.74 per cent were men and 61.75 per cent women.

Even in 2017, the percentage of female voters was lower than that of male voters in the western state. About 70 per cent of men and 66 per cent of women cast their votes in the Assembly elections, according to the EC website.

Reasons behind the increasing turnout

Kumar, the Lokniti co-director, describes “women’s exposure to social media” as one of the key reasons behind their increasing participation in politics. “Most young women use mobile phones, even some rural women…compared to what was the situation a decade ago. One also cannot deny the fact that what people watch on social media shapes their voting or political preferences, to some extent,” he said.

Moreover, “the provision of reservation for women in local body elections, be it urban body elections or village panchayat elections, has managed to efficiently mobilise women to participate in the electoral process”, he added.

The participation of rural women in local and state politics, according to Lokniti’s data, is higher than that of urban women, who are more interested in national politics. “More than one-thirds of the seats constitutionally reserved for women are seen to be filled by women in local governments, which indicates that they are getting elected from constituencies that are not reserved for them,” Kumar said. The elected female representatives at the local level, according to Kumar, have been able to mobilise a sizeable proportion of female voters.

One needs to recognise that women in South Asia are not a homogenous group. Factors such as class, caste, religion and region determine their political participation both as candidates and voters.

‘Winnability’ still low for female candidates

The number of women winning the Assembly elections this year has increased in all the seven states, even though marginally.

The number of female candidates elected from Uttar Pradesh constituencies were 42 and 47 in 2017 and 2022, respectively. The number of female MLAs in Uttarakhand increased from five in 2017 to eight this year.

In Manipur, women got elected from five seats in 2022, up from just two in the 2017 Assembly polls. Goa too witnessed a marginal increase in the number of female legislators—from two in 2017 to three in 2022.

In Punjab, the number saw a significant increase in 2022. As many as 13 Assembly seats were won by female candidates when 93 women contested the polls. In 2017, six of the 27 female candidates were elected MLAs.

While parties in Himachal Pradesh fielded 14 female candidates, only one of them—the BJP’s Pachhad candidate, Reena Kashyap—could make it to the Assembly in 2022.

In Gujarat, though the number of female nominees rose from 22 in 2017 to 40 in 2022, their success rate dropped, with only 15 getting elected when 139 women contested the polls.

The concluding paragraphs of “Women & Politics: Changing Trends and Emerging Patterns,” published by Lokniti, states that “the ‘elusive’ factor of ‘winnability’ is used as a ‘mask’ to explain why a high proportion of women candidates are not nominated by parties” (142). “Male politicians are still hesitant to field women as candidates, mainly because they believe that they cannot win elections,” Kumar elaborated.

However, this is not an accurate picture, according to Kumar. “Winnability” can be understood as the proportion of men or women getting elected in an election compared with the total number of candidates, he explained. Accordingly, “when we look at the number of women who contested a said election (which is lower than that of male candidates) and those who got elected to Assemblies or Parliament, the winnability of women is higher than that of men.”

Other factors that determine women’s electoral participation

Another important factor behind women’s increased participation as voters in the Assembly elections, except in Gujarat, is that parties offer beneficiary schemes for women.

Reena Kashyap, the sole woman who got elected in Himachal Pradesh this year, attributed her win to the “BJP’s women empowerment policies”.

According to Kumar, “the political parties in power are coming up with a large number of policies that cater to women… Through these schemes aimed at helping women, the parties are trying to send a message that they care about women voters … And it is being done by all the governments, across parties, in India. Each of them has a separate section for women in their manifestos.”

“An increasing number of women voters, recognising and exercising their right to vote, have convinced the contesting parties to include schemes catering to women in their manifestos,” he added.

According to the Lokniti-CSDS data, “every one in three women” surveyed for the study stated that “development, governance and welfare-oriented factors” influence their decisions.

The future

Although the Women’s Reservation Bill, which provides a quota for women in Assemblies and Parliament, has not been passed, the increasing female turnout can possibly help determine the fate of political parties and their attitude towards both female candidates and voters.