A highway rescue act, a turtle with patched-up shell — and now a wait

The turtle's shell had cracked open, leaving a gaping wound in the area right around its neck — it didn't look like it would make it alive.

Former physics teacher Vikendra Sharma who rescued the turtle. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Former physics teacher Vikendra Sharma who rescued the turtle. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)“Look, she’s burrowing deeper into the mud… she’s preparing to lay eggs soon. Turtles bury their eggs deep in the mud,” says Vikendra Sharma in a high-pitched whisper, barely able to conceal his excitement.

For the last few days, the turtle, lying in a large green tub in Sharma’s foyer, has been recuperating from a recent accident that left it shattered. As Sharma gently moves the foliage, letting in a stream of light, the turtle pulls back into its shell.

Around 12:30 pm on July 8, Sharma, a former physics teacher, was on his way home to Budaun from a gau raksha sammelan in Moradabad when he got a call about a turtle in distress on the highway between Budaun and Bareilly. The caller had found an Indian Flapshell turtle (Lissemys punctata), a species that’s categorised as ‘vulnerable’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) red list of wildlife species.

The turtle’s shell had cracked open, leaving a gaping wound in the area right around its neck — it didn’t look like it would make it alive. What followed were a harrowing few hours at a clinic of the Centre for Wildlife Conservation, Management and Disease Surveillance of the Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI) in Bareilly, where the turtle went through an emergency procedure to put the shell back in place.

“She must have come under a car while she was trying to cross the road to get to a pond on the other side,” says Sharma, an animal lover who spends his days tending to rescue calls and treating animals at his rescue centre, 15 kilometres from his house.

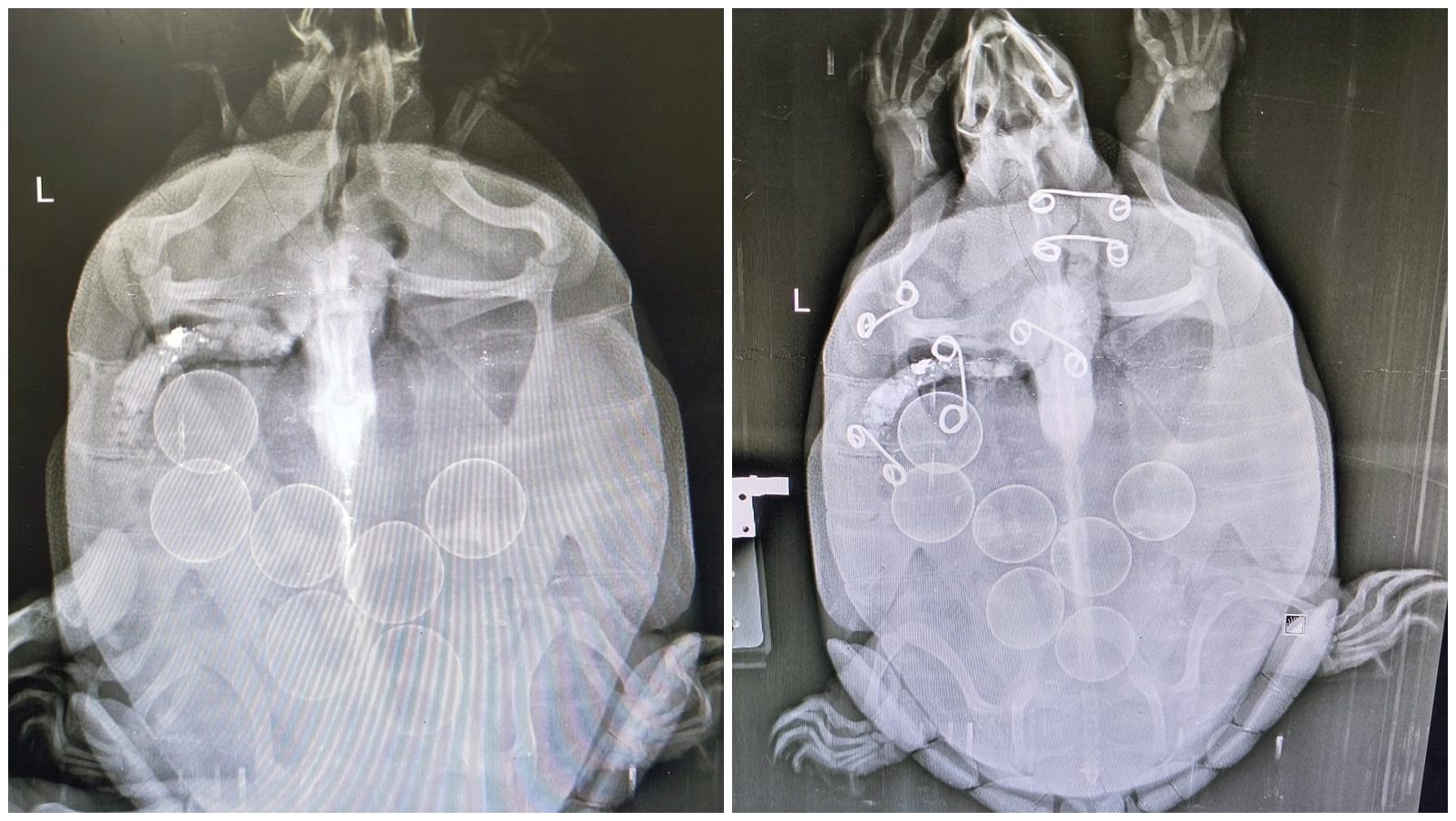

Pre surgery (Left), post-surgery (Right) X-ray of the turtle that shows its eggs. (Express Photo)

Pre surgery (Left), post-surgery (Right) X-ray of the turtle that shows its eggs. (Express Photo)

Several pieces of the turtle’s shell had fallen off and the wound on the neck was surrounded by multiple cracks, which the IVRI doctors said were “multiple displaced fractures” or “compound fractures”.

“I thought she was dead. I picked her up to move it to the side of the road before some vehicle would have crushed her further. Just then, she moved her limb and stuck out her neck. I couldn’t believe she was alive!” says Sharma.

He immediately called Dr Abhijit Pawde, Principal Scientist of the Department of Surgery and the Centre for Wildlife Conservation, Management and Disease Surveillance at the Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI) in Bareilly, someone Sharma has often reached out to after his various rescue acts – of cows, bulls and dogs. He once even sent a peacock and a rat to the institute for post-mortem procedures.

But never a turtle. So Dr Pawde, a stickler for rules, asked Sharma to seek the permission of the Budaun District Forest Officer (DFO) and the police before the endangered reptile could be transferred to the clinic.

As he waited for the permissions to come through, Sharma applied a generous layer of Betadine to the turtle’s wounds and held the shell in place with tape. When the nod finally came around 2 pm, Sharma took the turtle to IVRI in a basket. By the time he reached the clinic in Bareilly, it was 4.30 pm, half an hour left for the clinic’s closing time.

There were other issues too. The clinic had run out of orthopaedic glue and the doctors were unsure about how to proceed with reattaching the shell. “At first glance, it was obvious that it was a critical case. In fact, when we saw it for the first time, we thought it was highly unlikely that the turtle would survive,” says Dr Kamalesh Kumar K S, a PhD scholar who assisted Dr Pawde in the surgery.

“There was a lot of bleeding and there were multiple fractures on the carapace (the hard, upper part of the shell) and we had to ensure that there was no internal damage,” says Dr Kumar, explaining that the carapace’s shape and strength are critical for the turtle’s survival.

Explaining that the shell is the only protection turtles have, Dr Kumar says, “The shell is attached to the soft tissue below, making it difficult to treat internal injuries. If the fractures are not treated quickly, they can quickly become infected.”

While it did seem like a complicated procedure, doctors were optimistic because there were no missing parts to the shell and the jigsaw fell into place neatly. “Any small gap or hole left behind by a missing shard of the shell would have led to an infection,” adds Dr Kumar, who is currently pursuing his PhD from IVRI.

The initial X-rays showed that the injuries did not extend to the soft tissue. The doctors were also pleasantly surprised to see that the turtle was in fact pregnant with seven eggs. However, the conundrum still persisted: how does one reattach a shattered shell with no orthopaedic glue?

“At first we thought we would ask Mr Sharma to buy the glue but then decided against it because that would have taken too much time – we weren’t sure if he would have found it in Bareilly. So we sent him out to get some Fevikwik,” says Dr Kumar, before quickly adding that while the choice of the superglue may seem odd, it has been used in veterinary surgeries before.

While Sharma was out getting the glue, the surgical team put the turtle under mild anaesthesia and washed its wounds with antiseptic and antibiotic solutions.

The superglue was only meant to be a short-term fix and the shell’s parts needed to be fastened in place. Blouse hooks used in saree blouses were briefly considered — it could be glued in place with wires hooked across them, keeping the shell tightly in place. But again, time was running out and the clinic did not have blouse hooks in ready supply.

Incidentally, Dr. Kamalesh’s doctoral research at IVRI – he’s attempting to recreate stainless steel replicas of animal hip joints to make hip replacement surgeries for dogs and cattle cost-effective – requires him to use stainless steel orthopaedic wires and dental cement for making hip joint moulds.

The surgical team decided to use these orthopaedic wires as hooks to keep the shell’s parts in place. The shell parts were then fastened into position using bright pink dental cement.

With that, the turtle was put back in the box and handed over to its rescuer. “We have instructed Mr Sharma to keep the turtle in not more than two inches of water, so that the water doesn’t touch its wounds and infect them,” says Dr Pawde.

For now, the doctors are cautiously optimistic about the turtle’s chances of making it alive. “We’ve asked him (Sharma) to bring it back to us after 40 days so that we can remove the dental cement,” says Dr Kumar. “If it’s alright after 10-15 days with no infection, I think it has a good chance of survival.”

Back at Sharma’s house in Kalyan Nagar in Budaun, which Sharma shares with a group of monkeys, dogs, pigeons and a cat, it’s the turtle that’s getting all the attention. “Turtles bury their eggs deep in the mud,” he says, picking up the turtle and stroking its head. “I think I’ll name her Mallika – a queen,” he says, before adding, “I think I won’t feel as bad if she dies after her eggs hatch… at least she’ll be survived by her baby turtles. But if she does survive, I’ll release her near a big pond with no roads nearby… or the Ganga, maybe.”