A granddaughter writes: Before CJI Ahmadi, there was Aziz the prankster

Justice Ahmadi was part of the nine-judge bench in the 1994 S R Bommai v Union of India case which placed the guardrails on the imposition of President’s rule over a state under Article 356 of the Constitution of India

Former CJI Ahmadi with his granddaughter Insiyah Vahanvaty in Pune in 2022. Photo Credit: Shaurya Roy

Former CJI Ahmadi with his granddaughter Insiyah Vahanvaty in Pune in 2022. Photo Credit: Shaurya RoyAt a time when India was caught in the throes of the independence movement and the allied powers were embroiled in World War II, a teenager who went by the name of Aziz Mushabber Ahmadi was involved in far simpler pursuits — getting into street fights and playing pranks on the local police in Surat.

It was beyond anyone’s expectations that this “wild, uncontrollable child” with a “zest for adventure (that) could not be contained” would go on to become a lawyer, let alone a judge and eventually the Chief Justice of India — only the third Muslim to ever be CJI. Before he moved to the Supreme Court, where he was CJI from 1994 to 1997, Justice Ahmadi was a judge of the Gujarat High Court and earlier, was part of the bar in the Bombay High Court.

It is this seemingly audacious arc that Justice Ahmadi’s granddaughter, journalist Insiyah Vahanvaty, traces in The Fearless Judge: The Life and Times of Justice A.M. Ahmadi. Published by Juggernaut, the biography holds a mirror to the life and times of a judge who has been at the centre of some of the most seminal judgments of independent India.

Justice Ahmadi was part of the nine-judge bench in the 1994 S R Bommai v Union of India case which placed the guardrails on the imposition of President’s rule over a state under Article 356 of the Constitution of India. In 1992, he was a part of another nine-judge bench in Indra Sawhney v Union of India, where the court recognised the ‘creamy layer’ exclusion in reservation for Other Backward Castes and upheld the 50% ceiling for reservation.

Aziz Ahmadi after his appointment as a judge of the Ahmedabad civil court in 1965. Special

Aziz Ahmadi after his appointment as a judge of the Ahmedabad civil court in 1965. Special

But as the author notes, it all began on a much discordant note for “prankster” Aziz, a young boy born in 1932 to a non-practising Dawoodi Bohra family in Surat.

“Bohras from that era reminisce about their school days with affection. Educated at Hindu-dominated schools taught by Hindu teachers, these cultured, well-dressed and soft-spoken children were teachers’ pets,” Vahanvaty writes.

Yet, there was at least one such Bohra youth, the young Aziz, who refused to play by any of these etiquette rules. The book talks of a prank that Aziz pulled off as a teenager.

Riding on their cycles fitted with kerosene lamps towards the Nanpura police station in Surat, Aziz and his friends rode through town “looking as innocent as the day they were born”. Those days, cyclists were required to have a light while riding at night. Aziz blew out his lamp just as they approached the policemen on their rounds.

Aziz Ahmadi, aged 9, in Kalyan in 1941. Special

Aziz Ahmadi, aged 9, in Kalyan in 1941. Special

“Farrrrrrr… the sound of a whistle. Leaping out of the shadows amid the charged air with a triumphant ‘Light kidhar hai (Where is the light)?’ was a portly constable. Red faced and panting, he was sure he had finally caught up to the rascals. Aziz responded calmly, ‘Bhai, tha… abhi batti olaayi gayi (Brother, the lamp was on; it has only just blown out).’ The constable, determined to get the gang of boys this time, responded, ‘Mein kem maanu (How do I know this is true)?’ ‘Toh dekh (Then look),’ said Aziz, grabbing his hand and placing it firmly on the scalding hot lantern that was, indeed, alight a minute ago. Amid a cacophony of yells and profanities, the constable snatched his smarting hand back as the boys, in a symphony of jangling bicycle bells and kicking up a trail of dust, pedalled away as fast as they could, guffawing like impish daredevils,” Vahanvaty writes.

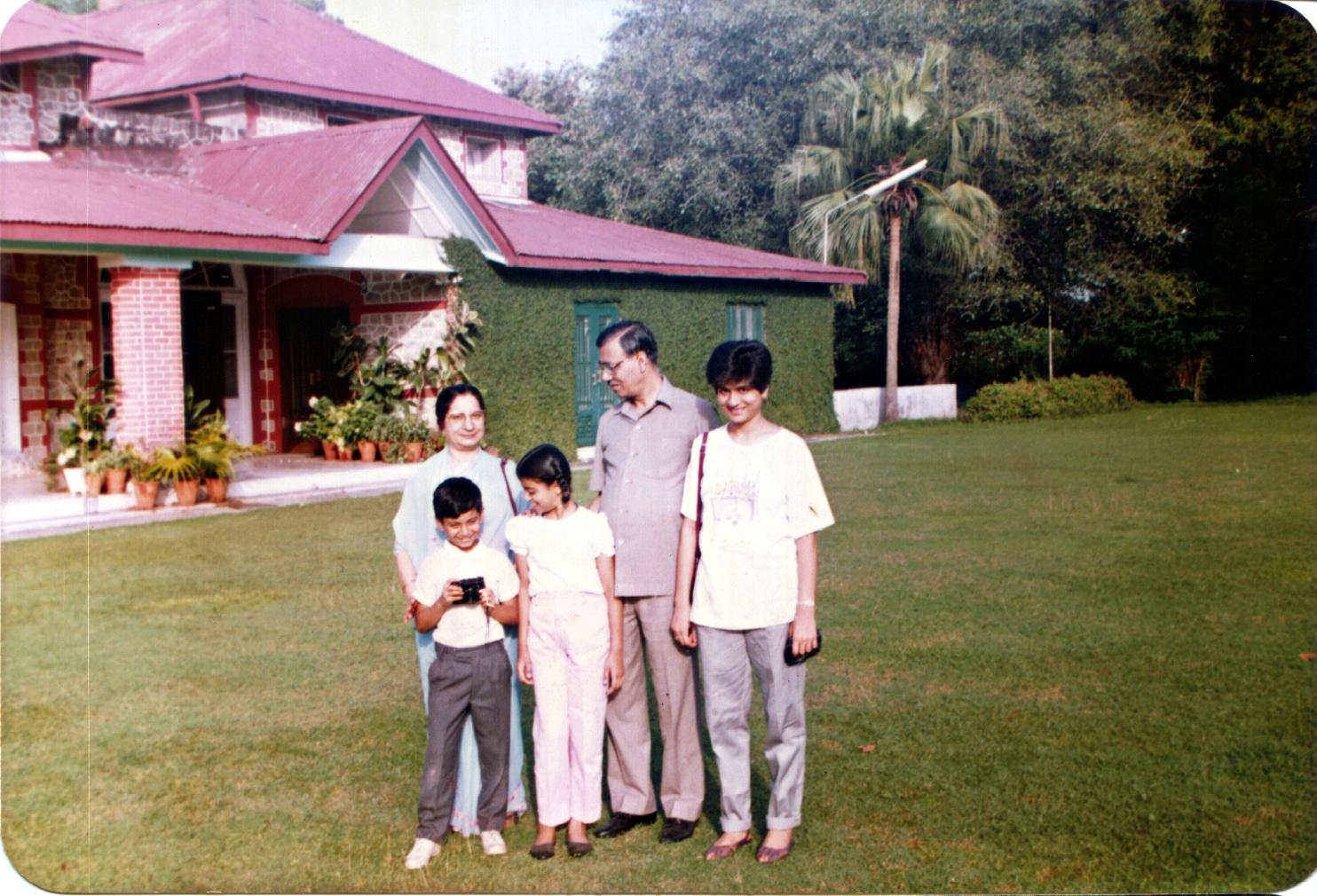

Amena and Aziz Ahmadi with their daughter Tasneem and grandchildren Insiyah and Adnan Vahanvaty in Dehradun in 1991. Special

Amena and Aziz Ahmadi with their daughter Tasneem and grandchildren Insiyah and Adnan Vahanvaty in Dehradun in 1991. Special

Born to Shirin Bensaab, a “no-nonsense woman who ran a tight ship”, and Mushabber Imran Ahmadi, a judge who “viewed his family’s conduct as a reflection on his own esteemed reputation and respect in society”, Aziz’s antics were the source of much friction in the Ahmadi household. As Vahanvaty puts it, “…Aziz was well acquainted with the back of his mother’s hand”.

His father meanwhile, dreamt of his son becoming an engineer and “Aziz was forced into the Science stream immediately after passing his matriculation exam…”

Justice A M Ahmadi at his official residence in Ahmedabad in 1985. Special

Justice A M Ahmadi at his official residence in Ahmedabad in 1985. Special

However, young Aziz’s true passion was not in science. “Borderline obsessive about sports, he embraced a wide variety of games — table tennis, football, cricket. Cricket, in particular, held a special place in his heart…This deep enduring love for sports was to remain a constant in his life until his Supreme Court days where friendly cricket matches between the bar and bench were a common activity,” the author writes.

What finally prompted his shift from the science stream to arts was an act of rebellion against his father.

In an attempt to steer his life in a direction of his choosing, Aziz had clandestinely applied to the Merchant Navy, “enthralled by the idea of a sailor’s life at sea, full of freedom and adventure”. However, when his father tore a letter he got in reply to his application, Aziz was furious.

(From left) Justice Ahmadi, Insiyah Vahanvaty, Shaurya Roy and then Vice-President Hamid Ansari at Insiyah and Shaurya’s wedding reception in 2009.

(From left) Justice Ahmadi, Insiyah Vahanvaty, Shaurya Roy and then Vice-President Hamid Ansari at Insiyah and Shaurya’s wedding reception in 2009.

As Vahanvaty writes, “He yearned to be unburdened by another’s expectations. And so, in his usual impulsive way, Aziz marched straight up to the administration office the very next day to request a change in streams. Now enrolled in Arts, he heaved a sigh of relief…A while later, his decision to study law immediately upon finishing his intermediate level would be guided by the same detachment.”

Justice Ahmadi’s decision to join the law, where his father’s presence would loom large, may seem like a counter-intuitive form of rebellion. However, as Vahanvaty explains, her grandfather was very clear about what inspired his decision, writing, “Making no secret of his motivations, he would openly state that his reason for choosing law at that early stage…was a calculated move designed to carve out more free time for cricket”.

Amena and Aziz Ahmadi with their daughter Tasneem at their family home in 1966. Special

Amena and Aziz Ahmadi with their daughter Tasneem at their family home in 1966. Special

That then is how an angry young man and his early choices unwittingly laid the groundwork for a legal career that would span decades, his pen signing on some of the most important judicial decisions in the modern era.

“As he would often joke in his later years, ‘I did not choose the law, the law chose me.’ It was a fact; the fates had deposited Aziz exactly where he needed to be,” writes Vahanvaty.