From assisting composers for survival to an Academy Award, here’s the MM Keeravani story

Keeravani’s oeuvre spans over 200 films and a clutch of languages including Hindi, Tamil and Malayalam.

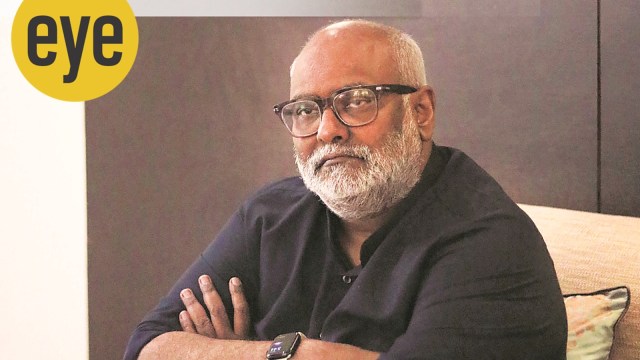

MM Keeravani won an Oscar for RRR's 'Naatu Naatu'. (Express photo by Pallavi TO)

MM Keeravani won an Oscar for RRR's 'Naatu Naatu'. (Express photo by Pallavi TO) When actor Irrfan was fighting an endocrine tumour at Princess Grace Hospital in London, filmmaker Mahesh Bhatt paid his old friend a visit. In a quiet moment, Bhatt wrote on social media, he held his friend’s hand gently and hummed, Maine dil se kaha, dhoond laana khushi/ nasamajh laya gham, to yeh gham hi sahi (I asked the heart to find and bring back happiness/ The innocent heart brought back sorrow, so well, then, sorrow it is).

The ditty was from Bhatt’s production, Rog (2005), a psychological thriller in which this wistful ballad sung by KK is picturised on Irrfan, an insomniac detective who while investigating the murder of a model, falls in love with the dead woman.

Created by MM Kreem, known mainly as a composer from Telugu cinema then, the melody was brooding and powerful with a certain haunting and ghazalnuma quality. Just like some of his other tunes – Tum mile (Criminal, 1995), Chup tum raho (Iss raat ki Subah Nahi, 1996), Gali mein aaj chaand (Zakhm 1998), among others, which were always a notch above the usual music of the time despite being set in a very similar milieu. The tunes have stayed on, as fond reflections. In the present, they’ve become invitations to enter his unique musical landscape.

So when MM Kreem, better known as MM Keeravani in Telugu cinema, walked away with the Golden Globe and the Academy Award earlier this year for Naatu naatu followed by a National Award last month, for the vigorous song and dance centerpiece in his cousin SS Rajamouli’s anti-colonial part-mythology-part-history action drama, RRR, it felt like an acknowledgment of Keeravani’s oeuvre that spans across 220 films in various languages. It was finally a step into the spotlight.

Here was a rambunctious dance number – a dance-off that represented the Indian struggle against colonialism, that had found attention from many, especially from the West. Tiktok and Instagram exploded over what felt, for many Indians, like just any other piece from Telugu cinema – with a catchy hook, an elementary tune, and heavily percussive and gritty rhythms – taken from the world of the street folk form of Kuthu.

Keeravani is acutely aware of the diverse opinions over his Oscar-winning success. “If I am sitting with a bunch of classical musicians, they will hate Naatu naatu. Art cannot be defined. I may find something artistic that others may find disgusting and vice versa. Naatu Naatu may be condemned by some people, who will call it a bulls**t song while others may dance to it. The opinions will exist till diversity does,” says Keeravani in a conversation in his hotel suite in Delhi post the acceptance of the National Award, his second.

There is an earnestness and candour in how Keeravani talks of his life and music. His sarcasm and sense of humour hit you slowly. “An advantage to working with Rajamouli is that if I am in the restroom, he can just knock on the door and ask any question; and I’ll answer. Others have to take prior appointment,” says Keeravani with a straight face. Twelve years older than the RRR director, he says he can “command him” to use one piece of music over another because he thinks it is better. “I cannot command another director like that,” he says.

In a career spanning over three decades, Keeravani may have finally received global recognition, but he says his life remains unaltered. “These are honours, of course. But they have not changed my life. Unfortunately, the only thing that will get you work is success at the box office. Not the Oscar, not the Padma Shri, not your good conduct. People produce films to earn money,” he says.

Naatu Naatu composer MM Keeravani (right) and lyricist Chandrabose with their Oscars (ANI)

Naatu Naatu composer MM Keeravani (right) and lyricist Chandrabose with their Oscars (ANI)

Born in Kovvur in Andhra Pradesh as Koduri Marakathamani Keeravaani, to painter and screenwriter Koduri Siva Shakthi Datta and his wife Bhanumathi, Keeravani began learning to play the violin when he was four. His father, a product of Sir JJ School of Art, put him under the tutelage of a neighbouring violin teacher. “My father, however, was my first guru, who taught me how to play the harmonium, compose tunes, modulate a sentence, just about everything,” says Keeravani.

Growing up on a steady diet of film songs on the radio, especially those by SD Burman (he distinctly remembers Kaahe ko roye from Aradhna (1969), by the age of 12, Keeravani was travelling with a band from Kakinada and would be featured as a guest child artiste who’d play Laxmikant Pyarelal’s Ek pyar ka nahgma on the violin. For about three years, Keeravani travelled with the band and loved the attention.

A science student, when he was unable to crack the engineering entrance exam, Keeravani turned to commercial music out of necessity. He began assisting Telugu composers K Chakravarthy and C Rajamani so that the money earned could sustain his large joint family. While his father and uncle (Rajamouli’s father) were script repairers in the Telugu film industry, the intermittent money wasn’t enough to support a 25-member family.

While Keeravani’s grandfather had been a wealthy zamindar (landlord) once, his father’s generation that had no steady jobs went through the money. “We have a saying in Telugu that if you sit and eat, even mountains will melt. The money was not there for my generation. I was the eldest, the sole earning member. Rajamouli was still in college. As an assistant, I was paid Rs 120 per song. We’d record two songs a day. I’d get Rs 240 plus Rs 25 conveyance. Since I’d take my cycle to work, I’d save that too,” says Keeravani, who for years put his head down and kept working, 365 days a year.

Keeravani’s first film as an independent composer was TSBK Moulee’s Telugu film, Manasu Mamatha (1990). But it was Ram Gopal Varma’s Telugu thriller Kshana Kshanam (1991), which put the spotlight on him. Varma was very excited after he found out that Keervani was a Stephen King fan and thought he would be able lend a slightly spectral tone to his film. “I was a newcomer and an absolute nobody. People wondered who is this Mr Keeravani who’s been employed by Ram Gopal Varma of Shiva fame. This made so many producers come to me like a herd of sheep,” he says. Varma’s film tanked, but by that time, Keeravani had bagged a bunch of Telugu projects. This was a turning point.

What cemented his position in the industry were also the 20 songs he composed for Annamayya (1997), a Telugu film, on the 15th-century composer Annamacharya. It fetched him his first National Award. This was also the time when AR Rahman was rising in the Tamil industry and was making a mark in Hindi film music. It wasn’t difficult for Keeravani, who was relatively shy and had a screen name but not much screen time, to be overshadowed by Rahman. But he persisted.

In the pre-internet days, the Hindi film industry was unaware of composer MM Keeravani. But they knew MM Kreem. Tum mile, dil khile, the memorable song by Kumar Sanu in Bhatt’s bilingual film Criminal, had won him much affection. People in Kerala however, did not know any of these two names. They knew him as Maragathamani, who was creating melodious Malayalam songs.

Seemingly inspired by Stephen King, the aliases brought about a comic opera of sorts. Once, producer and entrepreneur Ramoji Rao wanted to fire MM Keeravani, even though they had worked together on many films. The composer wanted to leave Rao’s film over a conflict with a director. Rao told one of his guys to go and hire a new composer named MM Kreem, who’d done an impressive Hindi album, Tanuja Chandra’s Sur (2002). “Back in the day, the secrecy was great fun,” says Keeravani.

After Keeravani worked with Bhatt in Criminal, the filmmaker offered the composer his most personal yet – Zakhm – set against the 1993 Mumbai riots and the story of an unwed closet Muslim mother who keeps hoping for her Hindu partner to marry her but dies after being burnt by a mob who takes her for a Hindu. It was a unique combination of politics, relationships and a director telling his personal story. Keeravani gave his soul to Gali mein aaj chaand nikla. It was conventional – there was Alaka Yagnik, the dholak and synth sound at the helm – yet it felt like a reminder of a song from the golden era.

Keeravani cherishes his relationship with Bhatt, his “guru” who is a “philosopher disguised as a moviemaker”. “Whatever he speaks, he wants to penetrate into the truth, thus shattering the hypocrisy. I have only done four-five films with him but it looks like I dedicated my whole life to Bhatt saab. It feels like that because those songs have a huge shelf life,” says Keeravani.

For Sur, a film that captures a complex teacher-student relationship with threads of fame, jealousy and creativity, Chandra wanted a certain madness in the music. “I needed audacity as well as a heart wrenching quality. Keeravani ji understood the soul of the story, its ebb and flow, the complexities of human nature in the story and the heights I wanted to touch in it, musically. He’s instinctive and has a childlike quality to him and likes to go in all sorts of wacky directions in order to come up with a tune that he feels is close to his heart. At the same time, he knows each musical note intimately,” says Chandra.

Another popular project was Jism (2003) in which he used 18-year-old Shreya Ghoshal’s innocent one-song-old voice for a seductress played by Bipasha Basu. “Here was a woman who used her body to get whatever she wanted. When you want to get a voice for such a character, people look for husky, bass voices. I wanted to change the pattern and go for a honey-coated dagger. The dagger was Bipasha Basu, the honey came from Shreya. A sweet voice for a villain. This is what I call going out of the box,” says Keeravani, who recorded Ghoshal laughing in the studio without her knowing it and used it in the final song.

Despite being steeped in music, Keeravani credits the authenticity and a certain maturity in his music more to his life than to his musical knowledge. At home he saw a lot of court cases, land disputes, which allowed him to interact with people from varied economic classes. “I remember someone coming home once and asking my mother for the money she owed. I remember hiding in the backyard because I didn’t want to see my mother embarrassed. These things are stored in my mind. When you see a lot in life, you learn to translate your life experiences into music. My strength is my life, not my musical knowledge,” says Keeravani. Which is probably where the haunting, somewhat primordial quality of his music comes from.

In 2015, there was news of Keeravani’s retirement, which shocked the music world. “It was a partial retirement. I wanted to retire from working with fools, certain directors. I decided to only work with sensible people,” says Keeravani.

This is when Baahubali (2015), a MM Keeravani musical arrived and swept the box office. A sequel followed in 2017. Mythology was being repackaged with technology in political and polarised times, and it worked. But it was RRR and Naatu Naatu that went ahead and took the world by storm. “One never knows what becomes viral,” says Keeravani.

At present, Keeravani is clear about working on his terms and as always troubleshooting. Unlike most composers, he says that he does not care for the non-availability of an artiste or if the person is demanding more money and not willing to travel to Hyderabad, where he records. “I work on a replacement. That’s how new talent is encouraged,” says Keeravani. He hates young musicians not being paid their due while celebrity artistes are paid huge amounts. “My basic payment is Rs 15,000 to a new chorus singer, even if she is not expecting it. The maximum should not exceed Rs 5 lakh. If that’s the case, I avoid the singer,” he says.

Keeravani has a busy season ahead—he is working on Gentleman 2, Rajamouli’s next, with Mahesh Babu, and Neeraj Pandey’s Auron Mein Kahan Dum Tha and Anupam Kher’s upcoming directorial venture. We won’t be surprised if one of them breaks new ground soon.

Take 5

Tum mile (Criminal, 1995): Moving from yearning to ecstasy, the piece was a sonic marvel when it came out. Featuring Kumar Sanu and KS Chithra, this one remains MM Kreem’s finest hour.

Gali mein aaj chand (Zakhm, 1998): Eloquent and emotional, this composition sung by Alka Yagnik and penned by Naqash Haider, was a lush and beautifully crafted piece placed in an otherwise intense film.

Awarapan banjarapan (Jism, 2005): With two versions — one sung by MM Kreem and the other by KK — and lyrics by Sayeed Qadri, the song powerfully conveys a lot of spiritual gravitas with Kreem’s cascading and profound tune.

Jaadu hai nasha hai: (Jism, 2005): Kreem used Shreya Ghoshal’s austere voice for the character of a temptress played by Bipasha Basu, which remains a masterstroke.

Kabhi shaam dhale (Sur, 2002): A large song with heaving strings, drums, Mahalakshmi Iyer’s power-packed voice, and a beautiful crescendo, the piece was infused with the spirit of old-time orchestras.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05