Ritu Sarin is Executive Editor (News and Investigations) at The Indian Express group. Her areas of specialisation include internal security, money laundering and corruption. Sarin is one of India’s most renowned reporters and has a career in journalism of over four decades. She is a member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) since 1999 and since early 2023, a member of its Board of Directors. She has also been a founder member of the ICIJ Network Committee (INC). She has, to begin with, alone, and later led teams which have worked on ICIJ’s Offshore Leaks, Swiss Leaks, the Pulitzer Prize winning Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, Implant Files, Fincen Files, Pandora Papers, the Uber Files and Deforestation Inc. She has conducted investigative journalism workshops and addressed investigative journalism conferences with a specialisation on collaborative journalism in several countries. ... Read More

An Express Investigation – Part Five | In diamond-rich Buxwaha, fight to save 2.15 lakh trees has many shades

Protests & legal battles have stalled mining project; villagers want jobs, health facilities, education

Deep in the Buxwaha forests, in Chhatarpur (MP), where preliminary drilling for diamonds was done. (Express/Ritu Sarin)

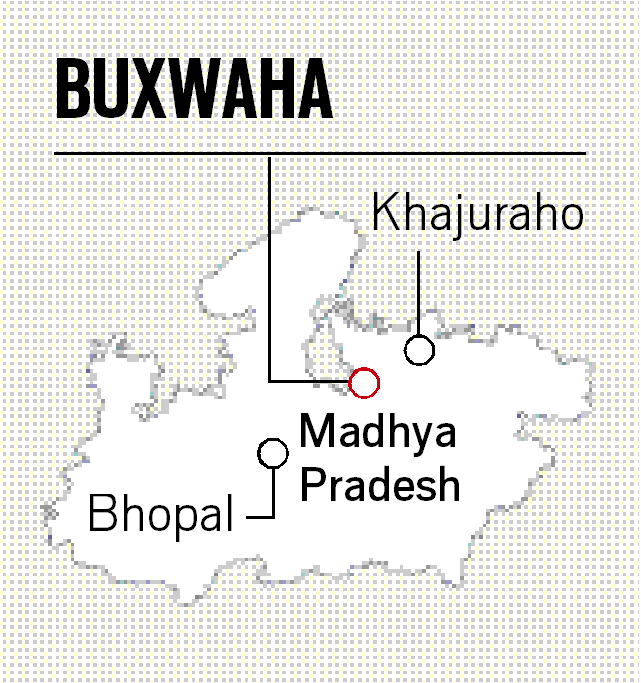

Deep in the Buxwaha forests, in Chhatarpur (MP), where preliminary drilling for diamonds was done. (Express/Ritu Sarin) The drive from the temple town of Khajuraho to the protected forests of Buxwaha is around 120 km and in the early morning, for almost half the drive, there is not a single vehicle in sight. The villagers of Buxwaha, in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhatarpur district, live mostly off the forest and survive on traditional agricultural practices. There is not a single large industrial plant either in the district, which is listed as under-developed in official records.

But deep under its dry deciduous forest, below the Teak, Salai and Khair trees, are rocks laden with Asia’s most precious diamond reserves — a whopping 34.20 million carats, according to prospecting mining estimates, embedded in 53.70 million tonnes of kimberlite, mostly untouched.

Buxwaha, however, is also Ground Zero of a conflict that lays bare the gap between India’s push to leverage its rich bank of natural resources and its global climate commitments.

Official records investigated by The Indian Express show that 2,15,875 trees need to be felled for an open cast diamond mine to operate here. And this, a visit to the site by The Indian Express and interviews with key stakeholders reveal, is now at the heart of a “trees for diamonds” battle with lawyers and activists stalling commercial extraction of the precious stones.

“The people of Buxwaha want their trees since they live off the jungles. They do not want diamonds. Moreover, these forests are in the Bundelkhand region, which has been hit by water scarcity. This is critical to the environmental debate over the diamond mine,” says Amit Bhatnagar, an activist involved in protests against the project. There is a cluster of 15 villages that ring the mining area that, together, have a population of 8,000 people.

An “active reforestation drive” will be conducted, counters Rahul Siladia, the Sub Divisional Magistrate (SDM) of Bijawar who is the jurisdictional authority. “The proposal is for trees in Buxwaha to be felled, stage by stage, over a 15-year period. The cutting of trees for the diamond mine and planting of new trees, both can go hand in hand. The people of the region should get employment and the wealth of the region should be utilised for them,” he says.

Underlining this narrative are concerns raised by a key panel of the Central Government’s Environment Ministry, viral social media campaigns with high-profile activists joining the “Save Buxwaha Forest” push — and an Indian mining company that has been waiting for a green signal for nearly four years.

Records show the state government granted a prospecting lease to Australia’s Rio Tinto in 2006, with the mining giant’s early estimates providing a peek into what lay underneath the backward forest belt. Over the next ten years, Rio Tino failed to make much headway before exiting India.

The diamond processing plant set up by Australia’s Rio Tinto is shut, in Chhatarpur, MP. The company exited India in 2016. (Express/Ritu Sarin)

The diamond processing plant set up by Australia’s Rio Tinto is shut, in Chhatarpur, MP. The company exited India in 2016. (Express/Ritu Sarin)

In 2019, Essel Mining & Industries Limited, the mining arm of Aditya Birla Group, won the e-auction for Bunder Diamond Block under which Buxwaha falls. Awarded mining rights for 364 hectares, about 40 per cent of the area proposed for Rio Tinto, the company promised a capital investment of Rs 2,500 crore and jobs for 400 people, mainly from villages from Buxwaha.

But it ran into stiff resistance on the ground.

Even as pictures of villagers hugging trees went viral in 2021, Narmada Bachao’s Medha Patkar and Swaraj India’s Yogendra Yadav joined the campaign. Several PILs were filed, including one in the Supreme Court by lawyer Preeti Singh stating the company was “vandalizing” natural resources and that cutting of 2.15 lakh trees would lead to “environmental devastation”. Another lawyer, Surendra Verma, approached the MP High Court stating that rock paintings estimated to be 25,000 years old inside Buxwaha would be destroyed.

The impact was immediate. In June 2021, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) issued an interim stay on tree-felling till environmental clearances came in. In September 2022, the Supreme Court asked petitioners to approach the MP High Court. And, in October 2022, the High Court ordered a stay on mining citing the archeological value of the rock paintings.

Felling of trees in large numbers is rare but not unheard of for various projects, such as expressways. In March last year, replying to a question in Parliament, the Environment Ministry had said that nearly 31 lakh trees had been cut for development projects in 2020-21.

The ambulance and equipment donated by the new mining company, Aditya Birla groups Essel mining in a govt hospital near Buxwaha forest (Express/Ritu Sarin)

The ambulance and equipment donated by the new mining company, Aditya Birla groups Essel mining in a govt hospital near Buxwaha forest (Express/Ritu Sarin)

But in Buxwaha, the records show that the diamond block had already been red-flagged by the Environment Ministry’s Forest Advisory Committee (FAC). On July 12, 2016, it warned that the block, located close to the Panna tiger reserve, would “potentially disrupt the landscape character”. And that a revised proposal from Rio Tinto, which held the prospecting licence at the time, was “highly dependent on surface extraction which would entail greater extent of forest land use and permanent loss of high quality forest trees”. Its advice: “underground mining”. A month later, the Australian firm announced its exit from Buxwaha.

With Essel taking over, the state government approached the FAC again. On March 31, 2022, records show, the panel reiterated its earlier observations — and said the government “has not provided enough justification” for using 204.6 hectares of forest land for dumping waste from the extracted kimberlite.

When contacted, Essel Mining said they would not like to comment as the matter was “sub judice”. On the ground, meanwhile, there is a lull in mining due to the court stay, and rising despair and apprehension.

“Rio Tinto hired 360 workers from these villages. When they left, they gave each of us compensation. I got Rs 3 lakh. But we know nothing about the new company, no one has come to meet us,” says Virendra Kumar Nishad, who worked as a security guard for Rio Tinto but has been jobless since. Nishad hails from Kasera village and accompanied The Indian Express to locations where early drilling related to the project was done — a 30-minute walk through forest trails.

“The new mining company should give us better education and health facilities,” says Ganesh Pratap Yadav of Teiyamar village, who was employed by Rio Tinto as a field supervisor.

Teiyamar’s former sarpanch Moti Yadav says village leaders and officials of Rio Tinto and Essel Mining had drafted plans to plant 10 lakh saplings as compensatory forest cover. Several “sabhas” (meetings) were held with the Australian firm for the initiative, and one so far with Essel Mining about a year ago, he says. “The 15 villages would have got double employment… in the mines and for planting new trees. But the plans remained on paper,” says Yadav.

As of now, the only visible imprint of Essel Mining here is the array of medical and diagnostic equipment, and an ambulance, they donated in 2021 to the local government hospital. As for Rio Tinto, there’s an old diamond processing plant on the highway close to Buxwaha. Its gates are sealed.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05