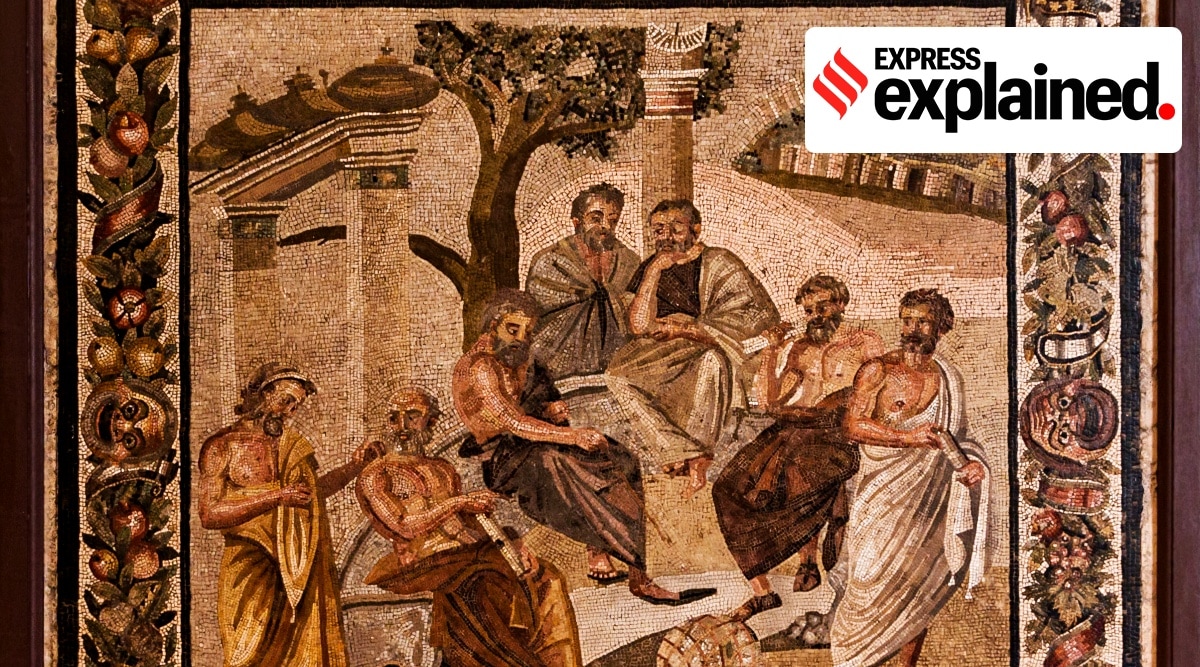

Greek philosophers were some of the earliest to form arguments about politics and governance and write about them. In Plato’s seminal The Republic, he said, “The heaviest penalty for declining to rule is to be ruled by someone inferior” when talking about capable people being disinterested in reforming society. And yet, he argued, they must be the ones to do it. Quotes of such nature, related to public life and social responsibility, are relevant for the UPSC examination.

What is the context of this quote?

In The Republic, Plato explains ideas related to Justice, Beauty, what should be the ideal system of governance, and more, through dialogues. He was a student of the philosopher Socrates and in the book, he presents his arguments through fictional conversations between people, including Socrates.

One of his arguments is that in a society, only specific people should do certain tasks. He criticises democracy (or the limited version of it that existed in Greece at the time). Plato is wary of the decision-making power of the common man and instead says that trained people called “philosopher-kings” should only be allowed to rule. They are to be taught the matters of statecraft and governance and should also be virtuous apart from being knowledgeable. In one of such dialogues, Socrates talks about why good men do not wish to rule over others.

Another version of the quote says, “The price good men pay for indifference to public affairs is to be ruled by evil men.”

Why does Plato believe so?

In a dialogue led by Socrates, he says the purpose of both arts and governing is for the benefit of others. “…No one is willing to govern; because no one likes to take in hand the reformation of evils which are not his concern without remuneration… therefore in order that rulers may be willing to rule, they must be paid in one of three modes of payment, money, or honour, or a penalty for refusing.”

Story continues below this ad

Upon being questioned on what the last of these payments means, he says that good men are not inspired by the goals of money and honour. “Good men do not wish to be openly demanding payment for governing… nor by secretly helping themselves out of the public revenues to get the name of thieves. And not being ambitious they do not care about honour.”

So, they have to be persuaded by a penalty instead. What is that? When it is necessary, they must be induced to serve from the fear of punishment of being ruled by someone else in their place. Because if they do not rule, “inferior men” will have to do that job, he says. The idea of serving other people through public service, then, comes not from a place of personal interests of honour or money but from a fear of someone else failing to do their duty.

What can be interpreted from this quote about public life and duty?

Plato’s idea of philosopher-kings has been criticised for having dictatorial tendencies, for only allowing certain people to be involved in governance based on narrow, unclear ideas of what being “good” is. But the theory that good people are unlikely to be inspired to do something based on only material benefit has some truth to it. Many religious teachings also agree that to be good means to do well unto others for the sake of it, not for personal gain.

Story continues below this ad

And so, to become a part of public institutions should not be guided by one’s own goals, he says. Instead of thinking what might be in it for ourselves, we should think of the contributions we can make to improve life for other people, and think about what happens if someone else takes our place – who might not have similarly good intentions.

In that sense, this applies to other forms of participation in politics and public life, as well. When voting or engaging in politics, people who are privileged do not necessarily have anything to gain or lose in very direct ways.

However, people are often not motivated by the possible gains that can be made from such participation, like being aware of the world around them, contributing to political decision-making, improving the standard of life and bringing forward the marginalised in society. For instance, someone could wish to step out to vote in local elections or contact their municipal bodies’ representatives to help ease civic issues in their areas, but they might not do so because they feel they are unlikely to yield results.

In such a case, Plato’s call for active participation can show a path. No matter how likely one’s goals are to be achieved, one should still engage in public life for the betterment of society in order to not cede ground to malicious, ill-willed people.