Cape Verde, an archipelago of 10 islands in the Atlantic Ocean, became the second-smallest nation (after Iceland in 2018) to qualify for the FIFA World Cup on Monday (October 13). Less than 24 hours later, India crashed to an embarrassing defeat to world number 158 Singapore in Goa, thus failing to make the cut for the 2027 Asian Cup.

In their own ways, both results were astonishing and evoked contrasting emotions.

The heartwarming story of Cape Verde — 815 times smaller than India in terms of land area and with a population that is less than two per cent of New Delhi — from the fringes of African football to the cream of the world game is exactly the kind that makes the World Cup the single-most compelling event in sports.

India’s inability to feature even in an expanded, 24-team Asian Cup — despite a far bigger population, more players, better grounds and a league in which players are paid in crores — points to a hopeless situation and an alarming slide.

The population angle

It is tempting to look at the two outcomes through the population prism. However, there might not be a direct correlation between population and success.

For, the tiny African nation tapped into its diaspora population; with players residing in Portugal, France and the Netherlands forming more than half of the squad. And while India may be a country of nearly 1.5 billion, almost half of its professional footballers who have managed to get playing time in the country’s top division league come from just three states with a combined population of less than 60 lakh.

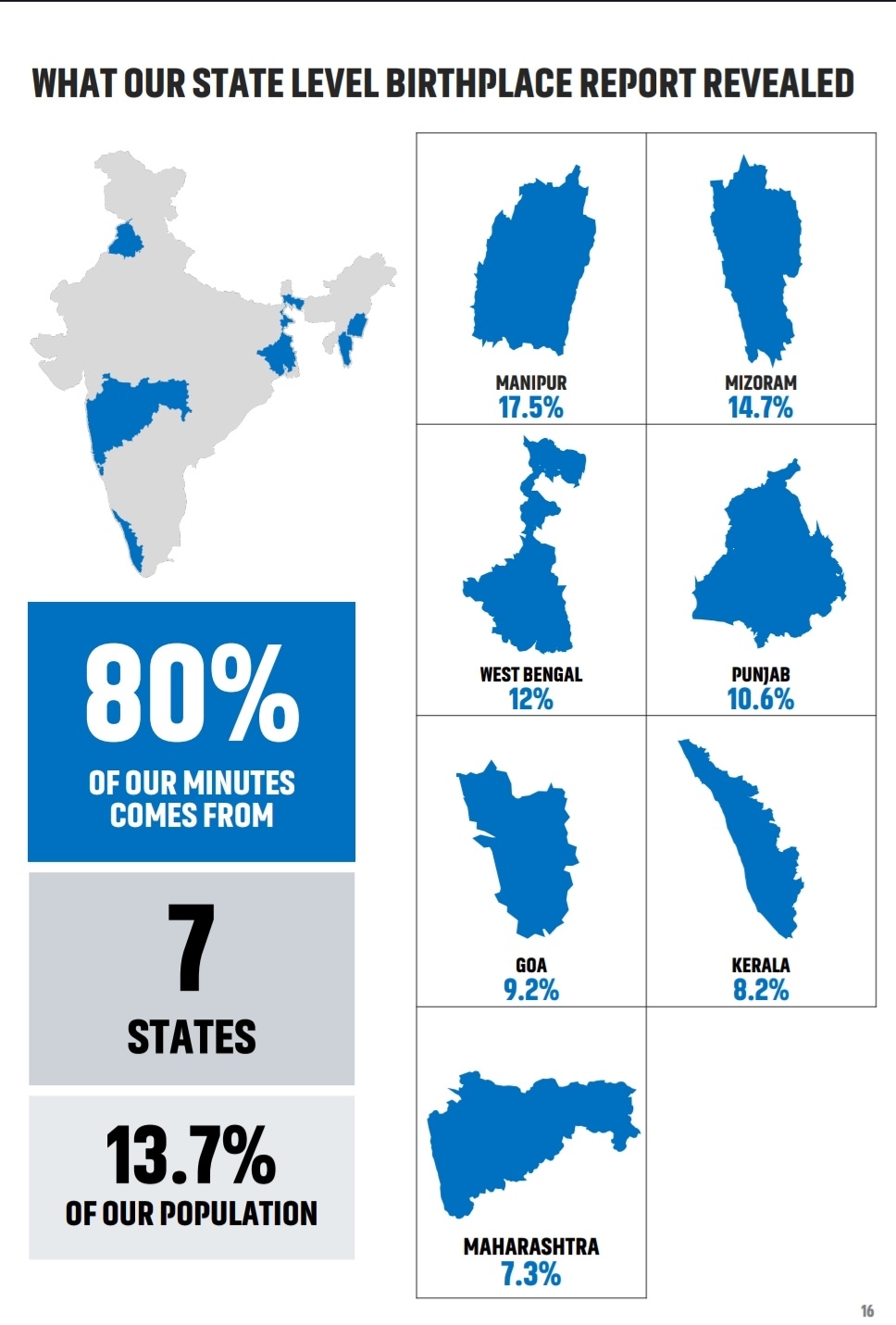

A recent study by UEFA ‘A’ license coach and former head of All India Football Federation’s (AIFF) Youth Development programme Richard Hood revealed that Manipur, Mizoram and Goa — among India’s smallest states — have produced players who have clocked 41.4 per cent of all professional playing minutes in the last 11 Indian Super League and I-League (erstwhile top division) seasons.

Story continues below this ad

Statewise concentration of football minutes. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report)

Statewise concentration of football minutes. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report)

Hood’s analysis further showed that out of the approximately 800 districts, “just 35 of them, home to only 7.4 per cent of our population, have produced more than 80 per cent of all professional playing minutes”. Seventeen of those 35 districts are in Manipur, Mizoram and Goa. West Bengal, Punjab, Kerala and Maharashtra account for the remaining 18 districts.

“Our professional player pool represents 198 districts in India,” the report stated.

Playing minutes indicate a player’s involvement in a match, their talent levels, and their impact on the team’s performance. For years, one of the main reasons cited for the Indian national team’s string of poor performances has been the lack of playing time the players get in the league. But even at a club level, Hood’s analysis showed that players from a handful of states are seen to be good enough by the team management to get consistent playing time.

Last year, a separate study conducted by Hood — who has also coached at a club level — highlighted that almost 65 per cent of the elite-level Indian footballers come from only five states whose total population, as per the 2011 census, is approximately 12.43 crore.

Story continues below this ad

Taken together, both reports highlight three things: that while Indians may be among the world’s biggest consumers of football, not enough of them play the sport at a high level; that talent is still nurtured in isolated pockets and widespread movement or strategy to develop a bigger pool of players is non-existent; and that the world’s most popular sport has made no inroads into the densely populated Hindi heartland.

Districts that have produced most talent

Although home to only 0.23 per cent of India’s population, five districts in Manipur — Imphal East, Imphal West, Thoubal, Bishnupur, and Churachandpur — produced players who played for 17.5 per cent of the total playing minutes in the I-League and ISL from 2014-15 to 2024-25.

Clustered concentration of football minutes in India. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report)

Clustered concentration of football minutes in India. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report)

The players from Mizoram had a 14.7 per cent share of the playing minutes, with most of them coming from Aizawl, Lunglei, Champai, Kolasib and Serchhip. West Bengal, led by Hooghly, accounted for 12 per cent of the minutes followed by Punjab (10.6 per cent), Goa (9.2 per cent, dominated mainly by South Goa talukas), Kerala (8.2 per cent) and Maharashtra, where Mumbai and Thane contributed to a total of 7.3 per cent of the total minutes.

Talent clusters exist in several sports, most notably in hockey (where Punjab dominates) and wrestling (Haryana). However, the research noted that in football, the “clusters are deeply concentrated” and suggested that they might not be productive when compared to international levels.

Story continues below this ad

For example, an analysis of the percentage of professional minutes secured by domestic players in the last season showed that across all positions — centre forwards, attacking midfielders, wide forwards, central midfield and centre backs — Indian players spent less time on the field compared to their counterparts in Japan, South Korea and Uzbekistan, which are the three 2026 World Cup-bound teams from Asia.

Moreover, even in the clusters that are producing a majority of footballers, the opportunities to play are fewer compared to mature football nations. “Even in leading clusters, we don’t play enough,” the report stated.

Statewise concentration of football minutes. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report)

Statewise concentration of football minutes. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report) Clustered concentration of football minutes in India. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report)

Clustered concentration of football minutes in India. (Richard Hood/Our Talent Clusters Report)