How cow urine from India found itself in van Gogh’s paintings

The colour known in the West as Indian Yellow was used by European painters in the 18th and 19th centuries. Indian Yellow, popular for its luminosity, was made using cow urine.

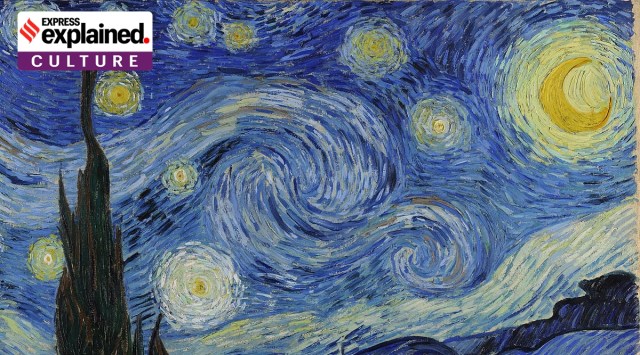

The Starry Night (cropped) with the luminous moon painted using Indian Yellow. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Starry Night (cropped) with the luminous moon painted using Indian Yellow. (Wikimedia Commons) Painted on a summer night of 1889 by Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night is one of the most recognised paintings in the world, depicting the dreamy star-filled night sky that appeared before van Gogh from the window of his asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence

While the original painting is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Delhi’s art aficionados have been treated to the Dutch post impressionist’s work in the ongoing exhibition titled “Van Gogh 360°”. Art lovers can now literally step into a magnified version of van Gogh’s work, with large projectors creating an immersive and intimate experience.

Interestingly, the yellow that Van Gogh used to paint the radiant moon in The Starry Night had travelled all the way from India. Named Indian Yellow, the shade was popular across Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, and The Starry Night is considered to be among the last masterpieces to have used it, before its production was outlawed in India.

We look at its history, origin and popularity.

Produced using cow urine

Known for its radiant and deep orange-yellow hue, it is believed that though artists in the West had been using Indian Yellow for centuries, they were unaware of its ingredients.

Its popularity, though, is evident from the fact that it found a mention in several notable publications. French writer-painter JFL Mérimée wrote in The Art of Painting in Oil and in Fresco (1839) that “the colouring matter is extracted from a tree, or a large shrub called Memecylon tinctorium … (which had) a smell like cows’ urine”, describing the colour as “a brilliant yellow lake”.

However, it was years later that British botanist Sir Joseph Hooker attempted to discover the details of the ingredients that made Indian Yellow. He reportedly wrote a letter to the Indian Department of Revenue and Agriculture find out. Hooker’s letter was responed to by TN Mukharji, author-curator and public servant.

Mukherji wrote that he had travelled to Mirzapur, Bengal, and observed that the colour came from the urine of cows that were given a special diet of mango leaves and water, occasionally mixed with turmeric, to get a bright yellow urine. The urine would be collected in earthen pots and placed over fire nightlong to attain a more condensed liquid, which was then strained and hand-pressed into sediment balls that were further dried in the heat. The piuris reached Europe through merchants sailing from Kolkata.

A report published on Sciencedirect.com in 2019 confirmed Mukharji’s analyses. Researchers wrote: “All the materials were shown to contain variable ratios of reported components of Indian yellow (euxanthic acid, euxanthone, and a sulfo-derivative of euxanthone), and some presented hippuric acid, a ruminant metabolite found in urine.”

Use in India and the West

The colour was widely used in India since the 15th century and is seen in traditional Mithila paintings of Bihar as well as Pahari and Mughal miniatures in the 16th to 19th centuries. According to reports, a yellow pigment called gorocana, also believed to have been made from cow’s urine, was also used for several rituals in India and also applied as tilak.

The Starry Night in the Van Gogh 360 exhibition. (Express Photo by Saumya Rastogi)

The Starry Night in the Van Gogh 360 exhibition. (Express Photo by Saumya Rastogi)

In the West, several artists took a liking for the colour that was supplied in the form of “chalky spheres” in Europe and had to be merely mixed with a binding agent to create paint. Its use was prominent as early as the 1700s, when artists such as Sir Joshua Reynolds used it in works such as The Age of Innocence (1788). The colour was also extensively used by JMW Turner in his oil and watercolours, and works such as The Angel Standing in the Sun (1846). The light emanating from the lanterns in John Singer Sargent’s Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885-86), was also painted using Indian Yellow.

Dutch painters like Jan Vermeer and van Gogh specifically admired it for its luminosity – something that can be seen in its use in The Starry Night.

Banning the colour

Though there is no concrete written evidence to suggest specific reasons, animal cruelty during the process of procuring the colour eventually led to a ban on its production in the early 1900s. The dehydrated cows “looked very unhealthy”, Mukharji had noted in his communication with Hooker.

In addition, scientists have pointed out that mango leaves are known to contain the toxin urushiol, which would also take a toll on the bovine animal’s health.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05