Why a ‘normal’ monsoon isn’t normal anymore for India

This is the eighth year in a row that monsoon rainfall in India has been broadly in the normal range. But behind this figure lie sharp regional as well as daily variations. Climate change is one reason behind this

While some days produced very heavy rainfall, prolonged periods went extremely dry. Similarly, a majority of the districts received very little rainfall during most of the season. This rainfall variability only seems to be increasing, possibly because of climate change.

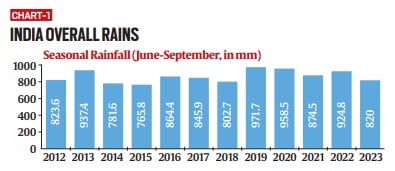

While some days produced very heavy rainfall, prolonged periods went extremely dry. Similarly, a majority of the districts received very little rainfall during most of the season. This rainfall variability only seems to be increasing, possibly because of climate change. The monsoon season this year ended with 94 per cent overall rainfall, making it the eighth year in succession that the seasonal rainfall has been broadly in the normal range. This makes it seem as though monsoon rainfall in the country has been remarkably consistent in recent years.

But that is far from being the case, as is evident from common experience too. There have been large variations in the distribution of rainfall, in spatial as well as temporal terms. While some days produced very heavy rainfall, prolonged periods went extremely dry. Similarly, a majority of the districts received very little rainfall during most of the season. This rainfall variability only seems to be increasing, possibly because of climate change.

Rarely normal

At the district level, rainfall has been highly erratic. During the four-month monsoon period, there have been very few instances of districts receiving normal daily rainfall. A new analysis by Climate Trends, a research organisation, found that districts getting normal daily rainfall was an extremely rare occurrence. Out of the nearly 85,000 district rain-days — 121 days of rainfall for each of the 718 districts — only 6 per cent were found to be normal.

In contrast, over 60 per cent of the daily district wise rainfall showed deficits of over 60 per cent, or no rain at all on days when rains were expected. The analysis also showed that large excess days — days on which districts received 60 per cent or more than normal rainfall — were the next most frequent instances.

“It is understood that normal rainfall data has been averaged out over several years and cannot be expected to indicate the consistency of rainfall, but the relatively minuscule number of ‘normal’ rainfall days experienced by India’s 718 districts does reflect a reality of being swung between extremes,” the analysis said.

The season also produced the second largest number of extreme rainfall events in the past five years, which compensated for the deficit on the dry days and brought in an illusion of normalcy (see table).

Dry North-East, drying Kerala

Even at the regional level, rainfall showed large variations. Northwest and central parts of the country received more than 100 per cent rains during the season, while eastern and North-Eastern regions got barely 80 per cent. The southern part of the country also had large deficits for most of the monsoon season. The region finally ended with 92 per cent rains for the season.

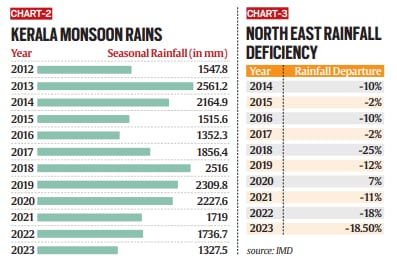

The deficiency in east and North-East India strengthens a long-term trend of below normal rainfall in the region. As pointed out by the Climate Trends analysis, the region has received less than 100 per cent rains in nine out of 10 previous years. On five of those occasions, the deficiency has been larger than 10 per cent. This region, at least the North-East, traditionally gets a lot of rain.

This year, the states of Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal received particularly poor rainfall, each ending with a deficiency of more than 20 per cent. Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram and Tripura also had more than 20 per cent deficit.

Kerala is one of the rainiest states in the country, but this year it finished with the largest deficit, 34 per cent. Rainfall over Kerala has been showing a declining trend in recent years, not just during the monsoon, a phenomenon that is not very well explained. But this year’s monsoon rainfall, 132.7 cm in total, was the least that the state has received in the past 12 years.

Climate change

The increasingly erratic behaviour of monsoon rainfall is usually blamed on climate change, but it is not that simple. There are many other factors at play. This year’s monsoon, for example, was expected to be hit by the prevailing El Nino in the eastern Pacific Ocean. In previous years, El Nino events have resulted in large rainfall deficits during monsoon. But it did not have a similar impact on the rainfall this year, at least in overall quantitative terms.

An extended cyclone on the western coast in June, and a prolonged bout of extremely heavy rainfall in the northern states in July, helped nullify the rain-suppressing impact of El Nino. August was the only month that seemed to have been under the influence of El Nino. In fact, it happened to be the driest August ever, producing just 64 per cent rainfall. But September once again brought good rainfall, despite El Nino gaining in strength.

Climate change has introduced a greater degree of uncertainty in weather events. The unpredictability in monsoon rainfall is likely to continue even if some drastic measures are taken to immediately bring down greenhouse gas emissions, known to be the cause of global warming and climate change.

The only coping mechanism right now seems to be better preparedness to face the unpredictable events. Increased emphasis on disaster preparedness, steps to remove the bottlenecks that worsen the impacts of extreme weather events —urban flooding, for example — and strengthening of climate resilience in new and old infrastructure are some of the things that are expected to attract greater attention.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05