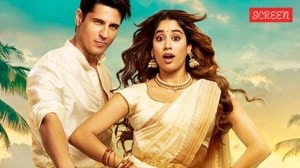

But while Bawaal was (correctly) criticised upon release — more for those ill-conceived Hitler parallels than its equally offensive gender politics — Satyaprem Ki Katha somehow got away scot-free. It’s one thing for nobody to have complained about it from the rooftops, but for the movie to have actually been praised for its perceived wokeness was frankly disheartening. This is where we come in, because forget being progressive, Satyaprem Ki Katha has to be one of the cruelest Hindi movies in recent memory — enslaved to troubling narrative tropes that you’d assume were abolished a decade ago; narrative tropes that we recently also saw in Hindi films such as Jayeshbhai Jordaar and Raksha Bandhan.

Story continues below this ad

The movie is so single-mindedly dedicated to arriving at a moment in which it reveals Katha’s big ‘secret’ — that she is a survivor of sexual assault — that it completely ignores a lot of the questionable behaviour that Sattu had been displaying over the course of two hours. He isn’t an outright monster like Ajju bhaiya from Bawaal, but they’re cut from the same cloth. Like Ajju, Sattu also believes that having experienced trauma — either mental or physical — essentially makes a woman defective.

He becomes instantly obsessed with Katha after first laying eyes on her, even though she tells him very plainly that she isn’t single. When he hears gossip about her breakup some time later, he decides to — wait for it — break into her house to surprise her. To be clear, they aren’t friends; they’re barely even acquaintances at this point, but the movie behaves as if this is a romantic gesture straight out of Aladdin. At least initially, before he discovers that Katha has slit her wrists and is dying before his eyes. Sattu gets her to the hospital in time, but the film has a habit of abruptly switching tones like this, leaving you with whiplash that you’ll be nursing until the next Kartik Aaryan-starrer rolls around.

The problem with Bawaal was that it was so pleased with its saccharine observations about misfortune that, in an effort to put things into perspective by comparing everything to the Holocaust (because how do you argue with that?), it completely forgot that it was doing a disservice to Janhvi Kapoor’s character. She should have been the protagonist of the film and not Ajju.

Satyaprem Ki Katha does this as well. Sattu’s arc is rather standard, but the movie is so devoted to him that it fails to recognise that it has a far more interesting character right under its nose. It’s one thing to ignore a character, but Satyaprem Ki Katha takes it a step further. The movie is actively cruel to Katha, the living embodiment of the Long Suffering Woman trope. Scene upon scene is designed to humiliate her, put her in the corner, and make her squirm — only to project Sattu as an angel. Miraculously, she lives through the entire film, but what she’s put through is indistinguishable from ‘fridging’ — the trope in which female characters are injured, raped, killed, or generally abused, as a plot device intended to move a male character’s story arc forward.

Story continues below this ad

First, she’s pawned off to him by her parents — Katha is clearly out of his league — like she’s a useless Diwali gift. It’s very dehumanising. Katha’s father believes that because she had an abortion — he doesn’t know that she was sexually assaulted — she is damaged goods. Sattu knows that he’s struck gold, and even though he knows something is fishy — he did, after all, witness her suicide attempt — he doesn’t question it. For most of the movie, all he seems to want more than anything else is to lose his virginity.

When Katha refuses to sleep with him, first by pretending that she is asexual, Sattu runs off to complain to her father for essentially chaining him to someone who isn’t willing to do her duty as a wife (which is code for, ‘she isn’t willing to satisfy my needs’). Later, after a romantic day out, when Katha once again says ‘no’ in absolutely unambiguous terms, Sattu backs off. As he should. But in the movie’s eyes, he now qualifies for sainthood. Must we really be asked to throw parades for men who show basic decency? Acknowledging the absence of consent isn’t a heroic deed, and people need to stop patting themselves on the back for it.

But let’s set Sattu aside for a moment and focus on the film’s actual protagonist, Katha. There are multiple scenes in which the movie forces her to relive her trauma, while the people around her either act oblivious or ashamed. A scene in which a nosy relative drops by and demands to know why she wasn’t pampered by Katha is deeply uncomfortable to watch, mainly because of how mean-spirited it is towards her. She eventually breaks down and tells Sattu’s family the truth, while he is literally playing the hero and beating up the man who abused her. She doesn’t know about this, by the way; he didn’t take her permission.

The most egregious moment, however comes in the film’s grand climax, when Sattu casually tells at least 50 people at a public gathering about Katha’s traumatic past, without so much as asking her if she is comfortable with him doing this. She should have been aghast, but she never stops him. It wasn’t his story to tell; it wasn’t his secret to reveal, but as usual, Sattu couldn’t help but make everything about himself. It’s easy when you have such a reliable accomplice in the movie itself. And even though he recognises that he shouldn’t have done this a few minutes later, the film doesn’t care to explain how he has come to this realisation, nor does Sattu seem even mildly remorseful about his behaviour. Instead, the movie proceeds to send him on another victory lap for having the wisdom to acknowledge that he was wrong. That’s not how things work.

Story continues below this ad

“Hero heroine ki jaan nahi bachayega toh hero kaisa (A hero isn’t a hero if he can’t save the heroine),” Sattu says at one point in the movie. And it takes him weeks to understand that his heroine doesn’t need a saviour at all; what she needs instead is an ally. But this happens literally five minutes before the end credits, in a two-hour-forty-minute movie that doesn’t understand the difference between empowerment and elevation.

Satyaprem Ki Katha can hardly be described as a feminist film, primarily because of how it treats Katha’s character. Not only does it rob her of agency and entrust her story to a man, this man happens to be someone that she was forced to marry; a man who throws a fit when she refuses to sleep with him; who happily accepts a shop and a car as dowry; who commits physical violence on her behalf and without her approval, and then blurts out her deepest secret in front of strangers. Satyaprem Ki Katha wants you to celebrate his actions over her resilience.

Post Credits Scene is a column in which we dissect new releases every week, with particular focus on context, craft, and characters. Because there’s always something to fixate about once the dust has settled.