Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

My relationship with my father still troubles me: Naseeruddin Shah

In a freewheeling conversation with one of his favourite screen idols Naseeruddin Shah, writer-director-actor Rajat Kapoor finds out about Shah’s complicated relationship with his father and how he came to write his memoir

Bollywood actor Naseeruddin Shah at his Mumbai residence

Bollywood actor Naseeruddin Shah at his Mumbai residence

In a freewheeling conversation with one of his favourite screen idols Naseeruddin Shah, writer-director-actor Rajat Kapoor finds out about Shah’s complicated relationship with his father and how he came to write his memoir

In the preface to your memoir (And Then One Day, Hamish Hamilton), you mention how the book began almost like a memory game, a challenge to test how much you remember.

That’s how it started. As long as it was fun to write about, I carried on. Then I’d pack it up and put it away — for a year at times — and not look at it. Later, I would remember something and I’d say, wow, I have to write about it.

So, now having written the book, are you nervous that people are going to read it?

No, I wasn’t nervous about people reading it. I just thought that nobody would read it (laughs). I didn’t write it with an audience in mind at all. I don’t live too much in the past, but this was a good excuse to indulge myself. I just thought I’d try to recall as much as I could and record it as accurately and objectively as I could, without giving in to my usual habit of getting over-wrought about things. And that’s what I am particularly proud of having achieved. I have never been able to talk about my complicated relationship with Heeba (his daughter from his first marriage) in interviews, but I could write about it at length in the book. My relationship with my father still troubles me because it never got resolved and there was no closure. There was a lot of bitterness, but having written about it, I found that I was able to overcome that bitterness and look at the relationship anew.

Naseeruddin Shah with Om Puri; with his mother and brothers (Courtesy: Hamish Hamilton)

Naseeruddin Shah with Om Puri; with his mother and brothers (Courtesy: Hamish Hamilton)

In the book, you mention that you had your first ‘conversation’ with your father after he passed away. There seemed to be a sense of closure, but now you say that you haven’t had that closure in life.

To some extent, yes. But it still comes back and bothers the hell out of me. Ever since I have had my own children, I realised the tremendous amount that we both missed out on. It was not done to put your arms around your dad’s shoulders and things like that then. In fact, he used to address his own father as ‘sarkar’ and he had to seek an appointment to meet him. So, from his perspective, he was a very chilled-out guy, I suppose. The same way that I think I am. But I realise that I have made quite a few of the same mistakes with my kids that my dad made. Not so much in trying to determine their lives for them, but in terms of trying to discipline them. Those were blunders.

Your father must have been quite a dreamer too. You write that he wanted to open a restaurant in England.

I think he was, but he kept it to himself. As Ratna (Pathak Shah, wife) was pointing out the other day, he lost out on the opportunity to be loved because of his idea of how a father should be. I didn’t know him. As I get older, I begin to understand him better and I think that he was actually quite a simple guy to understand. But I was too much of a kid and the distance became unbridgeable after a point. I really drove him up the wall.

Of course, there was this whole idea of what it meant to be a man at that time. One had to be of a certain kind to be considered masculine.

My mamus (maternal uncles) were my heroes. They were everything that I thought a man should be. Bandook vandook (guns), girlfriend, leather jackets, jeans, dark glasses, cigarette, tractor, ghoda (horses). That is the kind of atmosphere I grew up in — skinning black bucks and cocking guns and discussions that went ‘aam ka baag itne mein bika (the mango orchard sold for this much).’ It was unreal.

How did you move away from that?

No, I think I still carry a lot of it.

How?

In the irrational way I respond to things sometimes (laughs). The-easy-to-take-offence attitude. Settling matters with your fists, that kind of thing.

You do that?

I did. Not any longer.

Was anyone else in your family interested in acting?

There are a lot of people in my family who should have become actors. My nana- nani (maternal grandparents), mamus — they were tremendous actors (laughs). The voices they had, you could hear them from one end of Sardhana (near Meerut in UP, where they lived) to the other. And the passion with which they lived. Of course, they were great story-tellers. They were great characters, all of them. My dad’s side also had a highly eccentric bunch of people. But, of course, it was unthinkable to be actors — bhandelagiri karoge? Nautanki karoge (Will you perform, be an actor?)? My dad had a very hard time digesting that. He belonged to the provincial civil service, equivalent to the IAS. You know, the reason I say it is unresolved is because he didn’t live to see what I was capable of.

When you write about the first 20 years of your life, it seems textured; you write about what comes later rather matter-of-factly. Does it have anything to do with our emotional response to our childhood?

It could be because those recent events are so close that I didn’t want to get swayed by my emotions. It is safer to talk about events that are far away. Possibly, that’s the reason. Also, it is not in my nature to be unemotional.

I suppose I feel very deeply about those things from which I am far away. I feel safe in revealing them. There are many events in the latter part that I haven’t revealed. I didn’t want to offend anybody. I haven’t cared much about it in the past. But I thought this is the thing that is going to last, so, let’s not. It’s okay to ruffle a few feathers, but not to puncture anybody. Agar kuchh achcha kehne ko nahin hai, toh kuchh mat kaho (If you have nothing good to say, then don’t say anything).

But you were honest about yourself. It takes courage to tell the world this is who I am, this is who I was.

But wouldn’t you do that, if you were writing about your life? Isn’t it what the reader deserves?

You have dedicated the book to your sons Imaad and Vivaan, the only two family members who do not feature in it. What has been their reaction to the book?

They have not bothered to read it. And I don’t think they will for at least another 10 years.

Do you think luck had any role to play in how your career turned out?

Luck is a combination of factors. I consider myself to have been extremely lucky. But then I kind of foresaw the kind of films that were going to be made and realised that an actor like me would be needed in those films. When I saw Bhuvan Shome (1969), Sara Akash (1969) — I was in the National School of Drama (NSD) then — Teesri Kasam (1966), and then Ankur (1974), mujhe laga ki mujhe toh inn filmon mein kaam milega hi (I will definitely get work in such films). Let me try to be there.

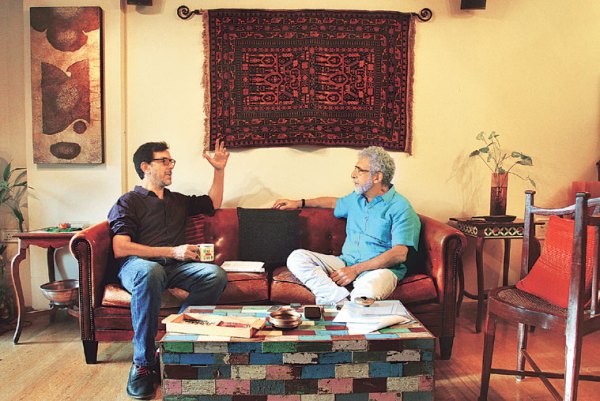

ROLE PLAY: Rajat Kapoor with Naseeruddin Shah during the interview (Source: Amit Chakravarty)

ROLE PLAY: Rajat Kapoor with Naseeruddin Shah during the interview (Source: Amit Chakravarty)

There is skill and there is perseverance, but out of 100 people with the same skill and tenacity, only a few will make a mark.

Those one or two, I think, are the ones who manage to be in the right place. And being in the right place again, is not entirely a matter of luck. NSD mein mujhe yeh soojha ki agar roti kamani hai toh filmon se hi kamani hogi. Toh yeh kaise hoga (I used to think that if I have to earn money, I would have to do so through acting. How will that happen)? Alright, even if I get a role as an inspector, I’ll do that.

Look at Om Puri. Even if he had not come to the film institute (Film and Television Institute of India, Pune), Govind Nihalani zameen khod ke nikal laata Om ko (Govind Nihalani would have dug Om out of nowhere). As an actor, you have got to learn your job as thoroughly as you can. If you know your job, then there’s nothing that can stop you. Because the bottomline is that only good actors will get work.

But actors like Nawazuddin (Siddiqui) have been around for 20 years and nobody seemed to care, but now, suddenly, everybody seems to want to cast him. It happened to Irrfan Khan too.

In those 20 years, both these guys really worked on themselves. Otherwise, they would not have been able to deliver when the time came. I have tremendous regard for them, not only for their perseverance but for the fact that they did not let it get them down. Chhote chhote role kar kar ke ab yeh sab (They acted in small roles to get here). They didn’t let it break their spirit.

My point is there must be many others as skilled and as talented…

I wish there were, but there aren’t people with that kind of faith in themselves. People make wrong choices.

But you made wrong choices too.

I made many wrong choices, in serious films as well. But I did not limit myself to any one category — that I’ll only do leading roles, which is a mistake some actors make. You shouldn’t define yourself in your mind that you are this.

I used to wonder that if I ever became a star, what kind of a star would I be. Na toh main gaane ga sakta, na toh main itna tagda hoon — Dharmendra-waale role bhi nahin kar sakta (I can’t sing songs, neither am I so strong that I can carry off roles such as Dharmendra’s). I used to think that I would probably manage to get the role of a prime minister in historicals. I would tell myself, let me prepare for this too. So that if the time ever comes, I would be ready.

I remember watching your debut film Nishant as a teenager. You made such an impression with the way you stammered and played your part.

Except for the film industry, everybody noticed it. It is probably the only film I watched in a theatre as I was excited about it. And the audience was responding to the character.

I went a bit far with the stammering. I did the same in Sazaye Maut (1981, directed by Vidhu Vinod Chopra) and Aakrosh (1980, directed by Govind Nihalani). At that time, I was deeply affected by Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate and wanted to emulate him.

How do directors of commercial films deal with you knowing that you don’t hold such forms in high esteem?

They don’t know what to do with me. Since I am not the one who generates the finance, I don’t get the plum parts. I fit into the roles that either no one will do or can’t do.

But these (commercial offers) keep coming to you.

It could be because they think adiyal aaadmi hai, par acting achhi kar lega (He’s an obstinate man, but he will act well).

Are you going to write about the last two decades of your career later?

I don’t know. It will become drier and drier. It will mostly be descriptions of films or plays. I may write a fictional book about these years. I did consider writing this book in the third person, but then I abandoned that idea. I also thought of writing about the acting exercises which I have developed over the years. But then I discarded that idea too as that would become too technical.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05