Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

Homebound: Neeraj Ghaywan explores how language becomes an instrument of oppression in his heart-wrenching second film

Homebound: Neeraj Ghaywan's film asks if you cannot find acceptance in your own country, then where else can you find home?

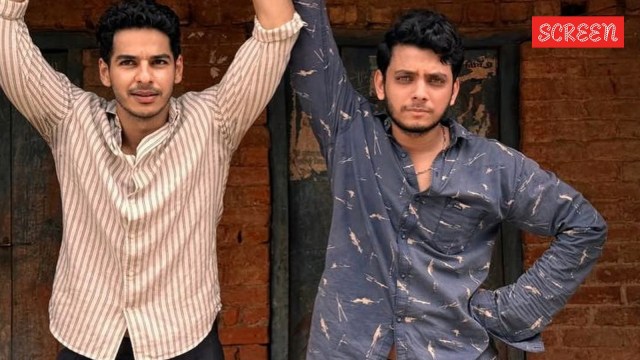

Homebound: The film is about two young men, Vishal Jethwa and Ishaan Khatter, one Dalit and one Muslim, grow up together in a small village.

Homebound: The film is about two young men, Vishal Jethwa and Ishaan Khatter, one Dalit and one Muslim, grow up together in a small village.Perhaps, in an example of the universe sending you a sign or reflecting your thoughts, a day after I saw Neeraj Ghaywan’s second feature film, Homebound, I came across a post on social media that had a quote by poet, writer and civil rights activist Maya Angelou. The quote said, “Hate has caused a lot of problems in the world, but has not solved one yet.” I couldn’t help but be amazed by how apt this thought was and how deeply it reflected the issues Ghaywan addresses in the film. Though religious riots and incidents of caste-based violence frequently make headlines in India, in Homebound, Ghaywan and his co-writers explore how language and the oral narratives of bigotry and prejudice are powerful instruments of oppression.

Two young men, one Dalit and one Muslim, grow up together in a small village. Their aim is to get a job in the police service and create a life where they can live with dignity and be spoken to with respect. Whenever he is asked his full name, Chandan (Vishal Jethwa) says it’s Chandan Kumar. He is embarrassed to tell people his full name, Chandan Kumar Valmiki, because those three words give away his scheduled caste status and determine people’s opinion of him. The words on a government form make him anxious, and he doesn’t tick the box for SC, insisting he is from the general category. Years of discrimination and deprivation have whittled down Chandan’s sense of self-worth to merely his name, or as he tells Shoaib (Ishaan Khatter) in anger, “My worth is limited to a box on a government form.” When asked in a government office about his caste, Chandan says he is a Kayastha. The officer suspects he is lying and proceeds to ask him his ‘gotra’ because merely belonging to a certain caste is not enough. Chandan has memorised the name of a gotra as well, hoping his lies and unwavering stare can earn him the respect of the officer.

Unfortunately, the officer, seemingly from an upper caste but economically disfranchised, taunts him about how donning a sher (lion’s) skin does not change a suar’s (pig) identity. Ghaywan shows how we have an entire vocabulary to insult, discriminate and associate people with notions of purity. The use of the word pig is not just to compare Chandan to an animal associated with filth or a dirty living environment, but also to remind him of his caste inferiority. In India, pig rearing has been associated with certain marginalised communities. Unlike cows, who have received more protection and respect than women, pig rearing is associated with impurity, which in tun leads to social ostracisation.

View this post on Instagram

While Chandan battles to get a job as a police constable, Shoaib finds a job as a peon in an office where a man learns his name and tells him not to touch his water bottle. While no one physically attacks or intimidates him, Shoaib is wounded with words almost every day. From being casually othered with comments like ‘voh log’ and ‘iske jaise log’ (those people/ people like him) to being humiliated at a public gathering with ‘jokes’ that question his patriotism, Shoaib is not just on the margins because of his poverty, but also his religious identity. Occasionally, there are glimmers of hope, like his boss, who encourages him and helps him get a better job within the company. It’s heartbreaking to see the surprise and gratitude on Shoaib’s face when he receives praise for his work and is told that he has potential. Having become so accustomed to snide remarks and keeping his head down, Shoaib soaks in even a spoonful of kindness like a parched plant seeking rain. But when the same boss stays silent at a critical juncture, it breaks his heart. Language maybe a weapon of oppression but silence aids systemic injustice. The weaponisation of language can only be defeated by using it to question every inherited bias or prejudice.

View this post on Instagram

But it’s not just external comments or prejudices that shape a person’s state of mind. The language we use to talk to ourselves and about ourselves can either offer us hope or break our spirit. When Chandan meets Sudha Bharti (Janhvi Kapoor), a young Dalit girl, she paints a picture of possibility and potential. Sudha looks at education as a means to overcome caste bias and tells Chandan that in a society where she will be expected to sit on the floor, she will make her own ‘kursi’ (chair) and carry it with her. It’s interesting how the word kursi, which is often associated with political power, here becomes a seat at the table, or an opportunity to be considered an equal. To Shoaib, Chandan and Sudha, respect or ‘izzat’ as they keep repeating, is far more valuable than the money they will earn. They realise that this intangible entity that can only be experienced through human interaction will heal not just their wounds but also those of their parents.

Instead of attacking a political party or blaming any political philosophy, Ghaywan paints a heartbreaking portrait of how those we elect to power have consistently failed to solve our most deep-rooted social problems. Whether that’s religious bigotry, caste discrimination, gender-based access to education, or bureaucratic mismanagement, Shoaib, Chandan, Sudha and their families are the faces of issues that remain unsolved and entrenched in our social fabric. Homebound never attempts to hold a megaphone and scream its message. Instead, the film’s commitment to creating a realistic portrait of the human condition forces you to confront your privilege and acknowledge that while we may all feel pain, not all of us have the means to escape it. Amidst the many questions the film raises in your mind, the most important one is this: if you cannot find acceptance in your own country, then where else can you find home?

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05