Senior journalist Pamela Philipose’s book on pandemic’s effect on India’s poor released

Philipose recounted how the book arose from 30 interviews conducted in August and September 2021 in JJCs and homeless shelters around Delhi.

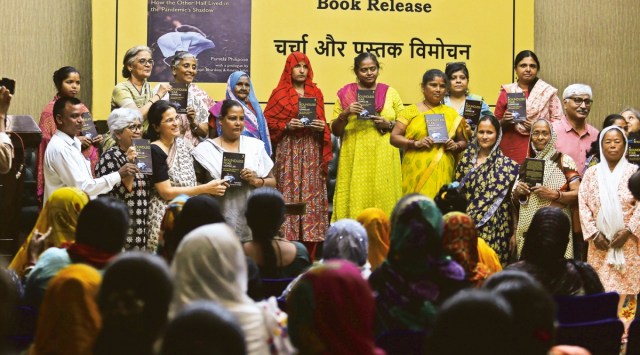

At the book launch. Anil Sharma

At the book launch. Anil Sharma Approximately a hundred fists rose in the air at the book launch of senior journalist Pamela Philipose’s A Boundless Fear Gripped Me: How the Other Half Lived in the Pandemic’s Shadow at Constitution Club on Thursday afternoon, rallying to cries of “Zindabad!” and slogans of working-class solidarity.

Most of the fists belonged to women, some with impatient children in tow, who journeyed from jhuggi jhopri clusters (JJCs) and homeless shelters around Delhi to participate in the book launch.

Through interviews with many of them, the book depicts their lives during the second wave of the Covid pandemic and how they faced sudden unemployment, unaffordability of rent, rampant starvation, domestic violence, shutdown of schools and geriatric care.

Apart from Philipose, many members of Delhi’s activist and social-work circles were present, including senior Supreme Court lawyer Prashant Bhushan, activist Harsh Mander, Ambedkar University economics professor Dipa Sinha, CPI leader Annie Raja, Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS) founder Anjali Bhardwaj and member Amrita Johri.

Philipose recounted how the book, which is priced at Rs 399 and published by Yoda Press, arose from 30 interviews conducted in August and September 2021 in JJCs and homeless shelters around Delhi. She cited the SNS network as pivotal in the effort, allowing her to tell the stories of “precarious lives in precarious pockets of India’s richest and most powerful city”. She said the stories are intimate and personal, detailing the rise of domestic violence during the pandemic, deprivation of nutritious mid-day meals for children due to shutdown of schools, and outsized responsibility of family welfare on the shoulders of women.

“That period will haunt us for years,” she said.

“Four hours’ notice was given before a nationwide lockdown, public transport was suspended, millions walked unimaginable distances back home, and income inequality increased. And amid all this, India got 1 lakh new millionaires in 2021, people who fully adhered to the adage, ‘Never let a crisis go waste.’”

Speaking at the event, Mander highlighted paradoxes in the government’s messaging during lockdown. He said appeals to work from home and to maintain social distancing were inapplicable to 90 per cent of the country working in the unorganised sector (without formal contracts) and 60 per cent living in single-room apartments.

Many women narrated anecdotes from the lockdowns, about how ration card pendency caused food shortages at home, husbands being laid off transferred the responsibility of earning – often with multiple jobs – on women, and the inability to pay rent became a widespread reason that labourers left cities to go back to their villages.

Sinha exhorted people’s advocacy for increasing the reach of ration cards and instituting the NREGA scheme, citing deficiencies in those systems.

“The struggle of many generations, and many women like you, led to these schemes which saved many lives during the pandemic,” she said. “There were definitely deficiencies – low-cost cooked food needed to be distributed and ration cards needed to reach everyone regardless of their position above or below the poverty line – but the grave situation forced policymakers to notice that many in the city won’t be able to afford rent or food if they are deprived of even a day’s work,” she added.