Chandigarh: From beautiful city to a struggling metropolis

“The inward-looking residential sectors separated by wide roads do not function as an integrated neighbourhood within the city. It can be observed that Chandigarh is lacking in social interaction, and the participation of its citizens in local affairs is relatively low... There is a need to rethink residential sectors regarding the pressure of upcoming population densities.”

The first master plan of Chandigarh, prepared by Albert Mayer in 1949, was designed for a population of 1,50,000. Now, the population of Chandigarh metropolitan area is 10,26,459, as per the 2011 Census.

The first master plan of Chandigarh, prepared by Albert Mayer in 1949, was designed for a population of 1,50,000. Now, the population of Chandigarh metropolitan area is 10,26,459, as per the 2011 Census. By Ar. Vipendra Singh Thakur

The population of urban areas has tended to increase over time, increasing the city size and conversion of rural areas to urban. Urbanisation is a complex process that results in a change in the built environment, a decrease in the forest cover and agricultural land, and impacts people’s livelihood. According to the United Nations, around 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, and it is expected that in 2030, the number will increase to 60%. Compared with developed countries, developing countries in Asia and Africa have faced rapid urbanisation for the past two decades. In India, one can witness more than a crore population in some major metro cities.

The layout of Chandigarh was the result of principles and theories developed from 1920 to 1930 in urban planning.

The layout of Chandigarh was the result of principles and theories developed from 1920 to 1930 in urban planning.

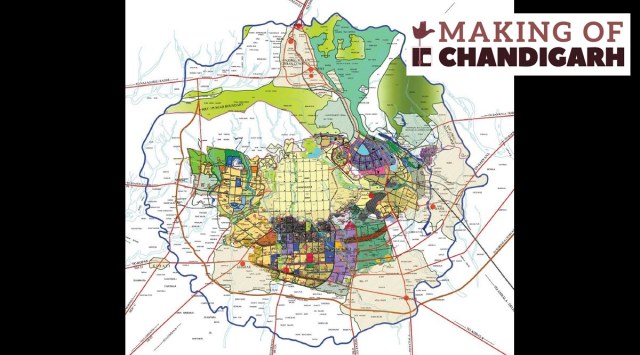

The peri-urban areas of Chandigarh are also increasing rapidly with decreasing agricultural land. The first master plan of Chandigarh, prepared by Albert Mayer in 1949, was designed for a population of 1,50,000. He suggested the “superblock” or “neighbourhood unit” suitable for India, where the population is inclined towards the village tradition, and people prefer to live in small communities.

Mayer’s plan for Chandigarh was fan-shaped, which was later converted into the orthogonal geometric grid by Le Corbusier. The layout of Chandigarh was the result of principles and theories developed from 1920 to 1930 in urban planning. The overall plan was the outcome of the multiplication of neighbourhood units rather than a single conceptual plan.

Camillo Sitte, an Austrian architect, and urban theorist, criticised the repetitive geometric grid and wide boulevards as monotonous and suggested returning to asymmetrical space enclosures and broken vistas similar to the cities of middle edges. Mathew Nowicki, a Polish architect, who earlier was the part of the Chandigarh project, expressed his views in his letter to Mayer, “In planning a city for ages of its future growth, it seems that we must continuously beware of trends in our present taste which might not be appreciated in the future”. His concern was to provide the possible flexibility for unpredictable future changes, which, when compared to the current situation of Chandigarh, seems problematic as the city has frozen in time in terms of upcoming metropolises in the country and the static nature of Chandigarh failing to provide lively spaces for youth to interact and make their own place out of the space allocated in the masterplan.

Unlike Nowicki’s flexible informality, Le Corbusier modified Mayer’s plan into a sectoral grid and preferred geometric ordering. The inward-looking residential sectors separated by wide roads do not function as an integrated neighbourhood within the city. It can be observed that Chandigarh is lacking in social interaction, and the participation of its citizens in local affairs is relatively low. However, the urban villages inside the sectoral grid still showcase the social integration and character of Indian towns.

There is a need to rethink residential sectors regarding the pressure of upcoming population densities. Another important need is to accommodate low economic groups inside the boundary of Chandigarh, who are providing various services to the city and have no provision to stay inside. Their presence may increase the city’s liveliness and reduce the pressure of high density on the peripheral boundary. The functionality of the city is also evolving from being an administrative centre to an educational hub, where youth from across India are coming for education and work opportunities, and it is hard to find any accommodation inside the sectors, as there is mostly government housing or low-rise private apartments. The lack of accommodation facilities is pushing this population to stay outside the sectoral grid and commute daily, creating mobility issues in satellite towns and peripheral areas of Chandigarh.

The population of Chandigarh city is around 9,61,587 (2011), while the population of Chandigarh metropolitan area is 10,26,459, which indicates that the major urban population is staying outside the city. These statistics are leading to rapid changes around the peri-urban areas of the city, and in the near future, Chandigarh will lose its peripheral agricultural belt.

There is a strong need to rethink Chandigarh as a metropolitan agglomeration and about upcoming challenges in the city and its periphery. The sectoral grid and developments in the urban agglomerations around Chandigarh should be considered as a collective entity and interdependent metropolis for the city’s future.

(Vipendra Singh Thakur is an Assistant Professor at Chandigarh College of Architecture)