Looking back at the borders of Bangalore Cantonment

Examining the duality of Bengaluru’s past and its impact on the city’s modern identity.

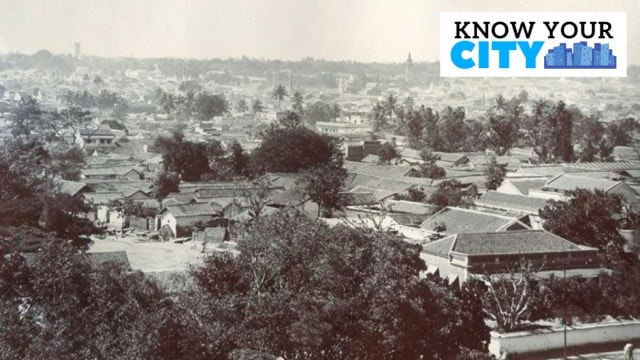

By 1881, the city’s status as a civil-military station was confirmed. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

By 1881, the city’s status as a civil-military station was confirmed. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)For many decades of British rule, there were in effect two Bangalores—the pettah, harking back to the original fortified town of Kempe Gowda, and the cantonment, where the British built the core of what was to become a modern city. Historian Janaki Nair explored the theme of the cantonment’s borders in a talk at the Bangalore Room titled “Did the Cantonment have boundaries?” on Sunday.

Looking back to the early days of the cantonment, Nair said, “When Mark Cubbon became the commissioner, he was faced with a new set of quandaries… Bangalore as a military station had no fixed limits. Certain portions of land were given for military use but these portions are intersected with others that were not given over by Mysore authorities.” This created issues of jurisdiction as far as the boundaries were concerned, one of these issues being the consumption of country liquor by the British soldiers.

For instance, by 1828, the Mysore royal authorities had disallowed the sale of a type of country liquor viewed as a threat to the discipline of European soldiers. The cantonment police therefore had the right to inspect the surrounding villages for six miles to prevent this.

Among other considerations, the British also focused on regulating health and discipline by addressing issues such as prostitution—a source of rampant venereal diseases that frustrated authorities—as well as ensuring ventilation in accommodation to maintain hygiene. The matter of jurisdiction was complicated by the fact that there were three different police forces: military, civil-military and durbar police. Nair noted that in large part the question of boundaries came up when British subalterns went out of the “Cantonment” areas to access commodities such as liquor. In fact, Lalbagh was at one point out of bounds for British soldiers, after they allegedly harassed some Muslim women.

According to Nair, by Cubbon’s time, he was engaged in a “long and bitter exchange” with the commander of the military station in Bangalore, over the question of whether it was a true cantonment (where the military would take precedence) or whether it was a civil-military station on a more even field. Nair noted that in effect, Cubbon was putting in place a property rights regime. She pointed out that military precedence would have deprived influential Indians of rights they had been accustomed to—something that Cubbon would have wanted to avoid in the aftermath of the Great Revolt in 1857. Indeed, Nair referred to a thwarted plot hatched by a diverse group of conspirators seeking to incite a rebellion against the British in South India.

By 1881, the city’s status as a civil-military station was confirmed. The boundaries at the time were marked by stones marked with the letters SB (Station Boundary). Some of these may have survived until the 1960s. The boundaries between the city and the cantonment became more fluid later, with inhabitants crossing them in solidarity with movements such as Khilafat and Quit India.

Speaking of places where the two societies came together, Nair said, “Koshy’s (on St Mark’s Road) was a unique quilting point where people could come from the more conservative city areas…” The expanding Cubbon Park was another one of these meeting points. Congress leaders such as K T Bhashyam also held up the civil-military area as a model to aspire to.