Long before she became the high priestess of modernism, Virginia Woolf, author of Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse, was a young woman experimenting with fantasy and humour. At 25, she wrote three whimsical tales about a “plain and very tall” giantess named Violet, who loved books, defied her governesses, and built, quite literally, “a cottage of one’s own.”

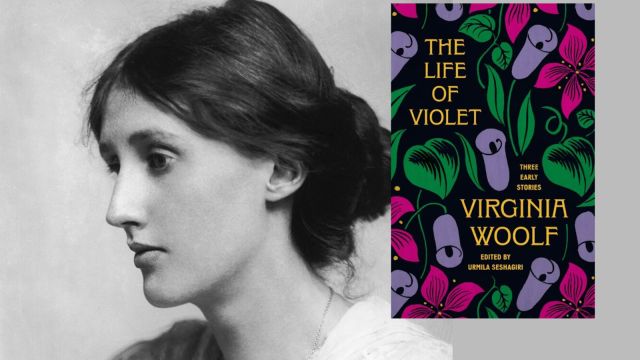

More than a century later, these forgotten works are being published for the first time. The Life of Violet (Princeton University Press, 2025), written in 1907 and newly edited by Urmila Seshagiri, a professor of English at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, was released October 7. The stories, part fairy tale, part social satire, reveal Woolf in an unfamiliar light: playful, mischievous, and quietly revolutionary.

A discovery in a country house

The rediscovery began with a chance remark in an English manor. While researching Woolf’s unfinished memoir, A Sketch of the Past, Seshagiri contacted Longleat House, a 16th-century estate in Wiltshire that holds papers belonging to Mary Violet Dickinson, one of Woolf’s closest friends.

Story continues below this ad

An archivist mentioned an original typescript titled Friendships Gallery, covered in Woolf’s handwritten corrections. A version of the manuscript already sat in the New York Public Library, which holds the world’s largest Woolf archive. However, this second copy, as it turned out, was no duplicate.

When Seshagiri examined the manuscript she realised she was holding a later, revised version of the same stories. The prose was more lyrical, the punctuation more deliberate. In one small edit, Woolf softened “shrieked” to “cried.” The effect, Seshagiri said, was “like seeing a cluttered room suddenly tidied up — its structure and grace revealed.”

The woman behind Violet

The “Violet” of the stories was inspired by Mary Violet Dickinson, an eccentric aristocrat and Woolf’s early mentor. Dickinson was witty, socially well-connected, and unwed, a rarity in Edwardian England. When Woolf, then Virginia Stephen, suffered a mental breakdown in 1904, Dickinson took her into her home, cared for her, and encouraged her writing.

Their friendship was intimate and complex. Woolf once called it a “romantic friendship,” and the language of their letters suggests a deep emotional attachment. Dickinson gave Woolf her first inkwell and introduced her to editors — small gestures that helped shape a literary career.

Story continues below this ad

In The Life of Violet, Woolf transforms her friend into a mythic figure, a giantess who conquers monsters and social expectations alike. The stories parody Victorian morals and celebrate female independence. Violet’s proud declaration that she will build “a cottage of one’s own” anticipates the argument Woolf would make decades later in her feminist classic, A Room of One’s Own (1929), that a woman must have money and a room of her own to write fiction.

The Life of Violet has been edited by Urmila Seshagiri, a professor of English at the University of Tennessee. (Source: useshagiri.com)

The Life of Violet has been edited by Urmila Seshagiri, a professor of English at the University of Tennessee. (Source: useshagiri.com)

A radical imagination

Though Woolf is best known for her psychologically intricate novels and stream-of-consciousness prose, these early tales show a different facet of her creativity. They mix the absurd and the sublime such as goddesses arriving in “Tokio” on the back of a whale, aristocrats turning into birds, and heroines who defy gravity.

Jessica Berman, editor of A Companion to Virginia Woolf, wrote: “What an extraordinary volume! …. These tales are laugh-out-loud funny. They are also profound early experiments in the fiction/biography blend that later gave rise to Orlando and the feminist musing about women’s education, marriage, and literary history that infuse A Room of One’s Own.”

A long journey to publication

After Woolf’s death in 1941, her husband Leonard Woolf, a publisher and political thinker, was offered the earlier versions of the stories. He declined, dismissing them as “a private joke.” The manuscripts drifted into obscurity, eventually surfacing in a London junk shop, where they were bought for a shilling by Tom Maschler, the future founder of the Booker Prize. Only later did Maschler realize that “Virginia Stephen,” the name on the pages, was Virginia Woolf herself.

Story continues below this ad

The stories found their way to the New York Public Library but were largely ignored by scholars, overshadowed by Woolf’s major novels and essays. The Longleat manuscript, with its hundreds of revisions, now shows that Woolf took the project far more seriously than anyone had imagined.

A delight rediscovered

The Life of Violet invites readers to see Woolf anew, as a young writer discovering her powers, inventing mythic women who refuse to shrink themselves, and laughing all the while.

In Violet’s magical world, where friendship is radical, and a woman’s imagination can defy gravity, we glimpse the spark that would ignite one of the 20th century’s most luminous minds.

The Life of Violet has been edited by Urmila Seshagiri, a professor of English at the University of Tennessee. (Source: useshagiri.com)

The Life of Violet has been edited by Urmila Seshagiri, a professor of English at the University of Tennessee. (Source: useshagiri.com)