The Dead Fish: Rajkamal Choudhary and the rot beneath modern life

Rediscovering Rajkamal Choudhary, the poet who diagnosed India’s moral and modern decay long before it became our everyday condition.

Rajkamal Choudhary, was a poet, novelist, and iconoclast who refused to be contained by movements or moralities.

Rajkamal Choudhary, was a poet, novelist, and iconoclast who refused to be contained by movements or moralities. (Written by Anchit Pandey)

When a culture forgets its rebels, it also forgets its conscience. Rajkamal Choudhary, poet, novelist, and one of the most unsettling voices in post-independence Indian literature, was long dismissed as a deviant, a misfit, a poet of “akavita” and hungry disillusion. Yet in an age that prizes productivity over meaning, and wellness over well-being, Choudhary’s The Dead Fish feels prophetic.

Rajkamal Choudhary’s relevance to contemporary contexts demands rediscovery, and The Dead Fish marks an important step in that direction. History’s fine print often conceals more than it reveals. Riding on canonical narratives, literary history frequently forgets or marginalises the rebels and vagabonds—the avant-garde, the protestant, the “a-aesthetic,” the anxious spirits who question the morality of their age.

In the Indian literary landscape, Rajkamal Choudhary, among other such “unfortunates,” is no exception. A poet whose life and habits have been voraciously discussed by admirers and critics alike, his writings themselves have received far less attention than they deserve.

Rediscovering the rebel

This new translation offers readers a fresh opportunity to explore Choudhary’s oeuvre and recognize his renewed relevance. His voice resonates deeply with the core anxieties of our times. Despite the labels and movements attached to him, Choudhary—both in life and writing—fought against imperfect conventions and lived on his own terms. A Sisyphean figure, he wrestled with the definitions of language, form, and morality while rejecting any illusory ideas of happiness.

For Choudhary, happiness was tangible yet unattainable, and it is in this paradox that his cynicism was born. The Dead Fish, in line with his broader corpus, embodies the anxiety of existence and the disillusionment that arises from irresolution. Why, then, this renewed compulsion to revisit a writer long labelled as a figure of the “Akavita” movement or Hungryalism?

Akavita, Hungryalism, and the question of belonging

The Akavita movement of the 1960s marked a break in Hindi poetry—its poets voiced disillusionment and pessimism, rejecting traditional poetic approaches. Alongside their Bengali contemporaries, the Hungryalists, they were inspired by the American Beatniks in their revolt against established institutions.

Choudhary, who was published briefly in their magazines, was later reduced to being “a poet of the movement” by progressive critics. But is he merely that? A modernist, a beatnik, a Hungryalist—as Arun Kamal calls him in the foreword to The Dead Fish—or something more complex?

The making of a disillusioned visionary

Hailing from Mahishi, Bihar—a remote and marginalized space even today—Choudhary’s early life demands a compassionate reading. He lost his mother early and struggled with his father’s second marriage.

These formative losses seem to echo in his writing, where women often appear incomplete, lacking, or as symbols of unattainable ideals. Yet, to read this simply as misogyny would be reductive. His characters are mirrors of his own contradictions—figures torn between idealism and despair, much like their creator.

The forgotten poet of anxiety

During a time when Hindi literary circles celebrated the optimism of Russian communism and the Progressive Writers’ Movement (Pragatisheel Sahitya), Choudhary’s works stood apart. While the progressives dreamed of emancipation, Choudhary delved into the depths of anxiety and existential crisis. His disillusionment with ideology and the rise of an elitist, self-centred middle class reveals a mind acutely aware of the decay of collective consciousness.

Choudhary’s acute understanding of class realities is beyond dispute. His depictions of lived experience, however, were too unsettling for the elite morality shaped by Brahmanical hegemony and Western capitalism. He asked questions that few dared to ask:

“What is left that is not a crime? Democracy? Commercial Dominion? War?” (Choudhary 22–23)

In today’s neoliberal world, these questions still hold weight. When hope appears in his works, it is swiftly negated. Local ethics are treated with suspicion, and the Enlightenment project—especially urban modernity—is ruthlessly dissected. His dissatisfaction stems from an absence of resolution, a lack that defines both his psyche and his art.

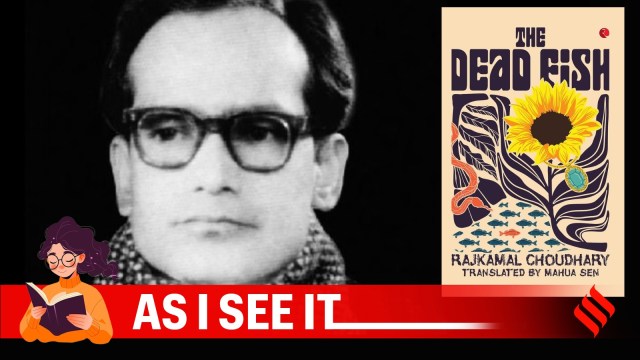

The cover of Mahua Sen’s English translation of The Dead Fish, which revives Choudhary’s unsettling vision of modern alienation and decay. (Rupa)

The cover of Mahua Sen’s English translation of The Dead Fish, which revives Choudhary’s unsettling vision of modern alienation and decay. (Rupa)

Calcutta: The urban wasteland

In The Dead Fish, Calcutta becomes a microcosm—a city of perversions, alienation, and moral decay. Through characters like Nirmal, Kalyani, Shirin, and Priya, Choudhary paints a grotesque portrait of modern existence. These are not heroes in a Sophoclean or Tagorian sense but victims of a modernity where decadence is the only enduring trait. Their “lack”—of love, of direction, of fulfilment—is the essence of their being.

The title itself is metaphorical: sterility and impotence define not just individuals but an entire civilisation. In this world, relationships are social contracts, sexuality is commodified, and freedom is an illusion.

Alienation, absence, and self-division

Alienation pervades every corner of Choudhary’s fictional universe. His characters, like their author, are haunted by absences—of love, belonging, and authenticity. Their lives, shaped by loss, are defined by inauthenticity and self-division. Is Choudhary a non-conformist, or merely a soul disillusioned by the order of things? Perhaps he is both.

Critics have often struggled to categorise him: modernist, postmodernist, beatnik, misogynist, or Hungryalist. Yet, his writing transcends such labels. His urban despair echoes Kafka; his moral scepticism recalls Nietzsche. His vision, unsettling and prophetic, dismantles illusions of beauty, progress, and hope.

Translation as resurrection

Translating Choudhary is no small feat. A multilingual writer capable of leaping from local dialects to Homeric allusions, he demands both intellectual and poetic sensitivity from his translators. Mahua Sen’s recent translation of The Dead Fish succeeds admirably, preserving much of his lyrical complexity and existential urgency. Her work, alongside efforts by Saudamini Deo and others, paves the way for critical re-engagement with a writer long neglected.

Sterility defines our age. The “wastelandish” image of The Dead Fish—echoing Eliot’s sense of impotence—captures the condition of a world where everything “new” is merely “renewed.” In this marketplace of recycled ideals, from da Vinci’s Mona Lisa to Che Guevara, meaning itself has become a commodity.

Choudhary, who knew desolation intimately, remains a prophet of our times. His vision of modernity’s exhaustion, of the futility of progress and hope, continues to mirror the crises of our own age. To understand him is to confront the anxieties that define us.

Rajkamal Choudhary was not a hero or an antihero—he was a prophet, and prophets demand empathy if they are to be understood. Lost writers like him deserve not just remembrance but resurrection.

Anchit is a poet and teaches English Literature in the PG Department of English, Patna University.

You can reach him at anchitthepoet@gmail.com

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05